When I was thirteen I stood on the Rainbow Bridge above the Niagara Gorge and watched a man strip naked, climb over the railing, and jump. The air was damp from the mist of the falls and the man was methodical as he removed his clothes. First his shoes and socks, then his trousers, his belt, and his periwinkle blue button-down shirt. His hands were steady as he folded each item and placed them neatly on the sidewalk. He patted the pile with his palm and dove headfirst into the gray air.

I ran all the way home, my backpack bouncing and smacking me in the small of my back. I fell breathless on the couch, turned on the TV, and stayed there until the nightly news came on. The man’s body had washed ashore. The paramedics didn’t know if he’d died before or after he’d gone over Niagara Falls.

One month later, when our shivery little greyhound Toby died, my mom, still dressed in her waitress uniform, turned to me after tamping down the wet soil and said, “He’s over the Rainbow Bridge now.”

We lived in downtown Niagara Falls then, and from our backyard I could see the sheet of mist that always shrouded the dirty, half-abandoned city. I pictured the man’s face, calm as a bank teller’s.

That year, 23 more people jumped. As the Maid of the Mist boat carried tourists to the base of the falls, blank-eyed men and women ascended railings, looked at the coursing green river below, and disappeared into the fog.

The only one that stuck with me was the naked man.

All I could think of was how serene his face had looked as he stood on the Rainbow Bridge with the deadly river tumbling below. I remember thinking, I hope I feel that peaceful before I die.

And eight years later, when I walked to the falls with a handwritten note in my pocket, I really did.

The thing about trying—and failing—to kill yourself is that you end up living the rest of your life like a ghost, haunting the places you used to go, watching your old job, your old friends, your favorite restaurant from a distance.

After my suicide attempt, my mom brought me home from the hospital to a living room filled with stuffed animals and Get Well Soon balloons. A grocery store sheet cake with no message sat on the coffee table.

“I got all of your favorite foods,” she said. “Macaroni and cheese. Chicken pot pie.”

I was dressed in gray sweatpants and a baggy white t-shirt the hospital had given me. I held a shopping bag containing jeans, a purple tank top, and fake gold earrings.

“You might try to cut your wrists with the sharp part of them,” the nurse had explained when she’d taken them away.

I looked around the living room. My mom had cleaned.

“I just want to go to bed,” I squeaked.

“I hope you don’t mind if…”

Before she could finish her thought, my aunts and uncles and cousins appeared from the kitchen.

“Surprise!” they said, their arms outstretched.

“It’s not a surprise party,” my mom hissed at them.

She turned to me and squeezed my hand. “I just wanted you to see some friendly faces, Holly.”

“Do they know?” I whispered.

She gave her head a quick little shake, which meant she was lying.

The aunts and uncles and cousins drank Michelob Ultra and ate the cake with their fingers and when I was feeling overwhelmed, I went to the bathroom and buried my face in my hands.

I could hear my cousins on the other side of the wall cracking fresh beers and talking in hushed tones.

“Wouldn’t it be funny if we got the bench where she left the note and brought it to this party?”

“Her mom did ask us to bring her a present.”

I was still clutching the bag from the hospital. I took out the purple tank top and held it to my chest.

A week later, I found the tank top in the back of a drawer. I put it on and walked to a bar down the street where I sat alone and drank Sauza Silver.

“Hey,” I said, to anyone who chose a stool near mine. “Did you know that this is the shirt I tried to kill myself in?”

They all gave the same tight-lipped smile and shuffled away.

“I’m not joking,” I called after them. “Come back.”

I stayed until closing time and then I went home and drank coffee at the kitchen table. At sunrise, my mom got home from work.

“I know what I want for my birthday this year,” I told her.

She startled at the sound of my voice.

“What are you talking about?” she asked, setting down the scuffed up green purse that she always carried.

“I know what I want for my birthday this year,” I said again.

She sat down across from me and looked at me with that new expression, the one that said: My daughter is crazy.

“What do you want?” she said. Her hands trembled as she lit a cigarette.

“I want you to help me pay for a Greyhound ticket to California.”

I half hoped she would try to talk me out of it, but instead she reached into her waitressing apron and pulled out a fistful of crumpled bills.

“Okay,” she said, placing the money in front of me. “This is a start.”

The engine sputtered as the taxicab deposited me in front of the drab motel. I hadn’t been to Niagara Falls in four years.

“I don’t understand why you insist on paying for a room when we’ve got a perfectly good couch here,” my mom said through the crackling phone line.

“That’s okay,” I said. “I can afford it.”

“I know you can, honey. But Earl and I would love to have you at the house.”

Earl’s parakeet shrieked in the background and I held the phone away from my ear.

I had no idea how Earl felt about attending my father’s mother’s funeral. I only knew him from the Christmas cards signed “from” instead of “love.”

It was just about as well as I’d known my own father, who existed in my memory as a gray shadow slumped over a bottle. After he’d died, my grandmother had started sending cards decorated with elephants and dinosaurs and “Thinking of You” type messages. When I’d tried to go over the falls, she’d sent me a card with a smiling bird on the front and a crisp $20 bill inside.

“The memorial service is at noon tomorrow,” my mom said through the phone. “Do you want to have dinner with us tonight?”

I looked out the motel window and saw the mist from the falls in the distance. I shut the blinds and turned to unpack my suitcase.

“No thank you,” I said. “I’m jet-lagged.”

I hung up and walked down the street to the same liquor store that my friends and I had used our fake IDs at in high school. I scooped up a handful of mini liquor bottles—Tanqueray, Jameson, Absolut—and went back to the hotel and drank them one at a time.

The elevator doors opened. My mom stood beside Earl in the motel lobby.

“Oh, Holly,” she said. “You look so beautiful.”

She reached her hand out and touched my hair.

“It’s so blonde,” she said.

“California,” I said, shrugging. They’d never been.

She wrapped her arms around me and I heard Earl say, “Aren’t you a little overdressed?”

“Hi Earl,” I said, sticking out my hand. He limply took my fingers. He was wearing a Buffalo Bills t-shirt and gym shorts. My mom wore a blouse that smelled like perfume and cigarettes.

“I thought this was a memorial service.”

“Yes, it is,” my mom said, rubbing my arm. “But it’s at Uncle Ryan’s house. You remember your Uncle Ryan, right? Aunt Carol’s ex-husband?”

“Barely,” I said. “Why is Grandma’s memorial service at Aunt Carol’s ex-husband’s house?”

“You know anyone else in this family with a backyard?” Earl scoffed.

“It’s going to be hard to walk in the grass in those high heels,” my mom said. “Do you want to scoot up to your room and change?”

I smoothed my hands over the linen dress.

“I thought this was a memorial service,” I said. “So I wore black.”

“That’s very thoughtful of you,” she said.

Earl snickered.

In a softer voice, she added, “I just want you to feel comfortable.”

My ex-uncle Ryan’s home was not a house.

“I’ve been doing construction,” he said, standing in his weed-choked front lawn. Behind him was the skeleton of a house. I could see all the way through to the backyard where someone had set up a rented party tent for the memorial service. The unattended ashes of a recent bonfire smoldered at the edge of the woods.

Ryan wiped the sweat from his brow with the bottom of his t-shirt. He spit on the empty flowerbed and reached out to shake my hand.

“Nice to meet––”

“You’ve met Holly before,” my mom reminded him.

I shook his hand anyway, and it occurred to me that he had never heard of the night I’d tried to jump.

A white truck pulled into the driveway.

“There’s your Aunt Carol,” my mom whispered. I thought of Aunt Carol’s sneer on the day I’d come home from the hospital and I felt the old urge to hide.

“Can I use your restroom?” I asked Ryan.

Earl snorted and gestured to the house. “You think he’s got a working one?”

Ryan had made a series of signs with notebook paper and magic marker pointing to the bathroom through the torn-up floorboards and discarded cans of paint. I followed them, stepping carefully in my high heels. From inside the scaffolding, the house seemed cavernous. I could hear the voices of my aunts and uncles and cousins as I closed the bathroom door behind me.

There was no mirror and no sink. Just a toilet and a medicine cabinet on the wall. Out of habit, I opened the medicine cabinet to look inside.

When I’d first moved to California, I’d been fired from a housekeeping job for going through people’s things. I’d tried to explain to the hotel manager that I wasn’t a thief, I was just curious.

Ryan’s medicine cabinet gave no clues. There was a stick of deodorant, a tube of toothpaste, and a bottle of aspirin. Everything was the generic Walmart brand.

I sat on the toilet, wondering how long I could get away with staying in the bathroom.

Voices drifted into the house. There were footsteps and the creaking wood from people walking through, passing from the front yard to the backyard. More voices. The voices of my dad’s brothers and a few of my cousins. I heard my name and some muffled laughter.

When I stepped out of the bathroom, I could feel raindrops falling through the scaffolding of the house. Above me, in the midst of the discarded tools and pieces of lumber, a pristine chandelier hung. I flicked the switch on the wall and was surprised to see it turn on. A breeze filtered through the house and the crystals sparkled, throwing flecks of shimmering gold light onto the wooden beams.

A low growl emitted from the corner and I turned to see a graying labrador lift its big square head. The dog rose to its feet. It was missing a leg.

“It’s okay,” I whispered, approaching it. The dog wagged its tail.

I crouched down in front of it and extended my hand.

The animal’s eyes were frosted over with blindness. Its wet nose twitched, sniffing.

In the backyard, the family I hadn’t seen in years gathered under the white tent, holding paper plates of pulled pork and potato salad. An open chest of ice held Labatt Blue and Bud Lite. A barefoot toddler with a head of blonde curls darted underneath chairs and tables, red-faced and screaming. Off in the distance, by the smoking ashes of the fire pit, Ryan stood holding a beer and looking at the forest.

Aunt Carol leaned against a table that held an urn and a guest book. She fixed her gaze on me and motioned to the urn.

“Did you see my mother is here?” she asked, and then burst into laughter.

“It’s nice to see you, Aunt Carol,” I lied.

“Look at you,” she said. “Who would have thought you’d turn out to be this big city gal?”

“It’s just Santa Barbara,” I said.

“Well from the way you ran off, you’d think it was the Emerald goddamn City.”

“I’m sorry for your loss,” I said.

“It’s your loss too,” she said, furrowing her brow. She leaned in. Her breath smelled like whiskey. “Don’t worry, honey, no one around here hardly talks about what happened with you anymore.”

I stepped underneath the tent, fully aware of all the eyes on me. The cousins smirked. My father’s brothers, a pair of pot-bellied men, raised their eyebrows at me. I went to the cooler, grabbed a beer and drank it fast. I wanted to go home. This was a mistake. I needed to be drunk.

From inside the house, I heard the three-legged dog howling.

I looked for my mom, an old instinct from childhood and then high school and then the months following the night at the falls. That old feeling that if I touched her all of the bad feelings would go away.

My high heel sank into the soft earth and I tripped and then caught myself.

“You okay, Holly?” one of the uncles asked.

Out of the corner of my eye I saw the other one circling his ear with his index finger—the loony-bin hand gesture.

It was hot under the tent. I scanned the crowd, looking for my mom.

I set down the empty beer and grabbed a full one.

A long-faced woman I’d never seen before put her hand on my shoulder and I jerked backwards.

“Are you okay?” she asked.

“No,” I wheezed. “Have you seen my mother?”

“I don’t know who your mother is,” she said.

Of course she didn’t. Who was she? Who were any of these people?

I chugged the second beer and made my way through the crowd.

“Mom?” I called. “Earl?”

I heard her voice as she entered the tent. I ran to my mom and hugged her.

“This one likes to cause a scene,” Earl said.

“Where were you?” I asked.

“We were just looking at the construction on the house,” she said. “Honey, you’re flushed. Let me get you some water.”

She should have known better than to make me fly to Niagara Falls for this, I thought. She wasn’t even trying to protect me.

“I don’t want water,” I said, breaking her embrace. “I don’t even want to be here.”

The sea of faces watched me as I hobbled out of the tent. Somehow I had lost a shoe. I took off the other one and threw it hard at the ground.

“I was thinking we should all go down to the falls tonight,” I heard Aunt Carol say.

“Sure,” one of the cousins responded.

“Are we supposed to take Holly to the falls while she’s in town?” my dad’s sister Janet, asked. “Or is she not allowed?”

Breathing hard, I walked towards the edge of the forest and found myself by the fire, which was now crackling again.

Ryan stood silently, unbothered by my wet face and my panting.

A trio of stumps were situated around the fire and I sat down on one, not caring if my dress got dirty.

“This was supposed to be a funeral,” I said to no one in particular.

Ryan withdrew two cigars from his pocket.

“You want one?” he asked.

I had never smoked a cigar, but I nodded. He bit off the ends of both, and handed me one. He lit his own and then offered me the lighter.

“I don’t know how to light it.”

Ryan looked ahead at the forest. The fire glowed on his weathered face. He was probably 50, but looked 60.

“I bet you can figure it out.”

I fumbled with the lighter until I got the cigar lit.

“See?” he said.

We watched the fire grow. I could barely hear the noise from inside the tent, but it sounded like someone was making a speech about my dead grandmother.

“It’s nice of you to host this,” I said. “I mean, you didn’t have to.”

“Carol and I been divorced eight years,” Ryan said, as if that was an explanation.

An errant mosquito buzzed around my ears and I swatted it away. I puffed on the cigar. It was actually kind of nice. Sweet, in a way.

I’d been sad my whole life. My mom and the doctors and the cops had asked for a bigger explanation, some grand event that had made me so sad. Was it because of my father’s death? Had I been hurt as a child? Was I trying to copy all of the other sad people who had gone over the falls?

The truth wasn’t a tidy enough answer for any of them.

I still remember how quiet I’d been when I’d slipped out of my bedroom that night, which was silly in hindsight because my mom was working the graveyard shift. The house was empty.

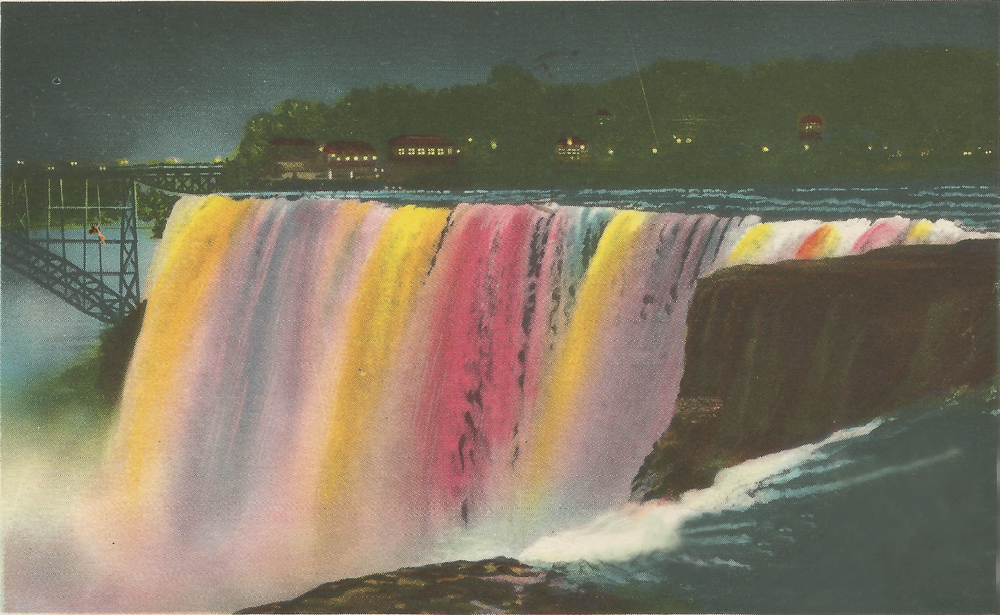

It was almost midnight, and the town was dark. The candy-colored lights were shining on Niagara Falls. A crowd on the observation deck lingered in the wet air, hoisting up cameras to photograph the crashing water and the lights of Toronto across the gorge.

I took the note out of my pocket and placed it on a bench, tucking it underneath a rock so it wouldn’t fly away. And then I made my way to the Rainbow Bridge.

I felt surefooted and strong as I climbed the railing. As the river thundered in the darkness below, I thought of the River Styx. We’d learned about it in middle school, how it was this scary black river that you had to cross in order to make it to the afterlife.

But when I got to the top of the railing, I couldn’t do it.

I don’t know how long I stood there, frozen and listening to the water roar, but someone must have called 911.

The lights of the police cruisers appeared.

“Get off the railing,” the officer said.

I climbed down to the dampened sidewalk and the officer wrapped a blanket around my body. When he saw my face his eyes flashed in recognition. He slid a pair of handcuffs around my wrists.

At the hospital, two nurses sat me down in a chair and stood above me, talking to each other in murmurs as they waited for the doctor.

“How many times has she tried?” one asked.

“Three,” the other one whispered.

“I can hear you,” I said.

They looked right through me.

“I’m a ghost,” I told myself.

“Don’t be foolish,” they said. “You’re alive.”

The aunts and uncles and cousins would say that I was doing it for attention, that I was a drama queen. That I was never going to go through with it anyway.

First the pills, then the knife, then Niagara Falls.

Do you think you’ll ever get married again?” I asked Ryan.

He shifted and picked up a long branch by his side. He poked the fire and it hissed like an animal.

“I think I’ll be alone forever,” he said. But he didn’t say it like it was a sad thing. He said it like it was a fact: Niagara Falls is 167 feet tall. The Rainbow Bridge is 1,450 feet long. I’ll be alone forever.

“Oh.”

What I wanted to say was I think I will be too.

“You know, I can’t put up with stupidity,” He jabbed at the fire again. “And oh boy, do things get pretty stupid sometimes.”

The cigar went out, so I set it down on a nearby stump.

“Why’d you say yes to them doing the memorial service here?” I asked.

Ryan let out a short laugh.

“That’s real funny,” he said. “You think they actually asked permission.”

The clouds were gray and the air felt thick. I’d forgotten how muggy Niagara Falls could be in the summer.

Outside of my apartment in California, the evenings were cool and smelled like cherry blossoms and every night at 8 p.m. I took my Zoloft.

In Niagara Falls, brick houses crumbled and one-eyed cats crossed vacant lots. And in the distance, the water flowed through the gorge and tumbled over the falls, indifferent.

“I think it’s going to rain again,” I said to Ryan.

“Looks that way.”

Underneath the tent, the person making the speech told a joke, sharing some anecdote about something my grandmother had said or done. The crowd laughed. I pictured the rosy cheeks of the aunts and uncles and cousins standing together like some kind of pack while my mom, off to the side, smiled her polite smile and dotted her eyes with a tissue at the appropriate times. I imagined the three-legged dog sleeping on his pile of blankets beneath the golden chandelier.

“I guess we should go stand under there with everyone else,” I said.

“Guess so.”

The rain fell harder. I didn’t get up.

“Do you really want to?” I asked.

Ryan opened up a beer and shook his head.

From where I sat on the stump in the wet darkness, I could see my whole family, standing together in the warm, glowing light beneath the tent.

“Yeah,” I said. “Me either.”