REVIEW // by Jason Harris

White Blood: A Lyric of Virginia by Kiki Petrasino

Sarabande, $15.95

In the spring of 2016, my maternal grandmother—Granny—passed away. I knew more about the end of her life than I did about any other parts of it. She was addicted to alcohol, smoked a lot, and laid in hospice care mute and immobilized from the damage the alcohol did to her organs. At her funeral, there were few people, most of whom I didn’t recognize, but they, we, loved her well. As with any passing of a loved one, I wanted to learn more about who she was as a person before the alcohol. For the next few years, I made phone calls and sent messages through Facebook to my mother and my aunt—my mother’s younger sister.

Growing up, I knew the maternal side of my family was small; there was Granny, there was my mother, her younger sister and brother, and then their two cousins. That was it. All that my mother knew of Granny was that she had a twin sister in her youth but was separated from her and then adopted by my great-grandmother. The only proof that I have that my Granny ever existed, save the stories my mother and aunt and uncle have of her, is a small laminated bookmark made out of her obituary. In the top left corner of the bookmark is a picture of my Granny—Abigail—and she is smiling. She looks happy. There is a gap in her two upper-front teeth.

If you are Black and American, then you too might have a story similar to mine. A story whose blood origin begins with more questions than documented truth. So when I read Kiki Petrosino’s fourth full-length collection of poems, White Blood: A Lyric of Virginia, I knew immediately that this book—situated around the speaker’s own search for genealogical truth through DNA tests and historical records—would be a guidepost, an answer to the question I often ask myself: What does it mean to know yourself through the history of your family and the country in which you were born?

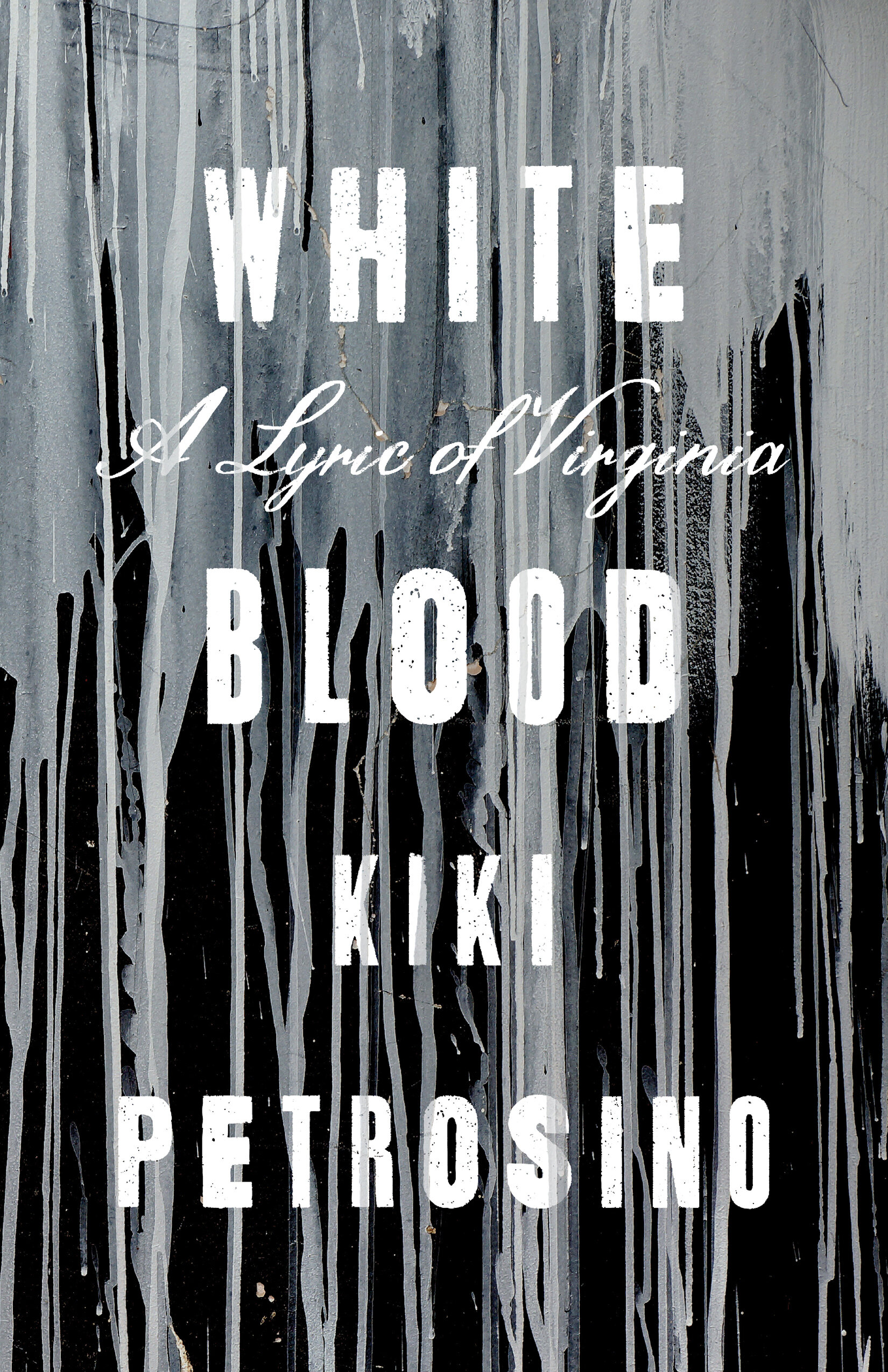

The cover of White Blood: A Lyric of Virginia reminds me of two things: Bloodwood trees and the history of the United States of America. Bloodwood trees, when damaged or illegally logged, will do what arborists call “bleeding.” The trees bleed because it is a healing mechanism the trees have adopted. When I learned about Bloodwood trees and Googled the image of one felled (and saw it “bleeding”), I felt uneasy. That uneasiness crept up in me while contemplating this collection’s brilliant cover and title—White Blood: A Lyric of Virginia. Across the cover of the book is the title and underneath is the author’s name, both in large white font. The title, unlike the author’s name, is written in cursive echoing the penmanship the United States of America used to write official documents in the 1700s (e.g. the United States Constitution, the Declaration of independence), documents that are grounded in racism. The words of the title alone, “white blood,” conjure the all-too-familiar term, “black blood,” also known as the one-drop rule. The twentieth century one-drop rule once relegated any person accused of having African ancestry, just one-drop, to a status of second-class citizenship. White Blood: A Lyric of Virginia is a reminder that in the systems we maneuver and on the grounds we walk, this country is soiled in something sinister, in something as invisible as DNA to the naked eye.

We meet our narrator after she has taken a DNA test to find the answer that many Black Americans have asked themselves, or will one day ask themselves: Who am I in this country? White Blood opens with the poem “What Your Results Really Mean: Western African 28%,” a documentary poem—a poem assembled with documents that exist outside the body and outside of poetry. Most interesting, though, is that the documentary poem, in White Blood, also exists within the body, as DNA. Petrosino documents the results of her DNA test through three erasure poems of the results, and the results vary: 28% of her DNA is from Western Africa; 12% of her DNA is from Northwestern Europe; 5% of her DNA is from North and East Africa. Each result is given the space for its own poem.

The form of these erasure poems, made from an ancestry test our narrator took, works magnificently in White Blood. Found poetry works here, particularly with DNA test results, because that is the eternal plight of Black Americans: feeling as if we are always recreating ourselves out of found materials: family photos, family heirlooms, family stories. Obituaries made into book marks. In the first erasure, “What Your Results Really Mean: Western Africa 28%,” our narrator says Your DNA has roots that / cluster and / spread and through that spreading, our narrator knows that she must find the point at which that DNA first spread, which is through the ghosts of her ancestors. These poems act as more than just erasure poems, or documentary poems, they are investigations into how we, as Black Americans, continue to remake ourselves, to find ourselves anew in a country buried in old, horrific truths.

After discovering the test results, our narrator learns that she is a descendant of the Free Smiths, a black family from Louisa County, Virginia. Our narrator receives four genealogical messages, which come to her as poems, from the Free Smiths. In the first message, aptly titled “Message from the Free Smiths of Louisa County,” a member of the Free Smiths says to their descendant: We saw no reason to hum Old Master’s name… which turns the narrator’s search for answers in her family’s history on its head. She is reminded that sometimes neither history nor what it stole from her is worth questioning over and over and over. Instead she understands the wounds that historical violences have had on her present day but refuses to let those wounds, those violences, spoil her future, or the future of generations to come. In this first message, the speaker of the poem, one of the Free Smiths, says to our narrator: we know you keep looking for proof that we existed, but you’ll find little here. The repetition in this poem (which too feels like a strand of DNA), aligns with the wisdom that the Free Smiths are trying to impart on our speaker: these messages are urgent; please listen to keep on living. Survival, as a Black person in a country like the United States of America, always happens in a state of urgency. A member of the Free Smiths ultimately shares with our narrator: Little child, we’re at rest / in the acres we purchased. Those days of / bondage were old folks’ business. The grown folks / buried us deep. The concept of history and one’s ancestral line living past the present day seems to be hidden in the truth that survival happens best when ancestors are allowed to rest and the living are allowed to go on living.

After unearthing her ancestor’s identity, the Free Smiths of Louisa County, Virginia, our speaker begins grappling with her own identity and with the history of Virginia and its violent treatment and exploitation and commodification of her people. Without having to revisit the monetary benefits white families gained from enslaving Africans, our speaker dissects the intersectionality of who she is: a free Black American who can read and write and perform humane work and be paid for that work.

In “The Shop at Monticello,” our speaker says: I’m a black body in this Commonwealth, which turned black bodies / into money. The juxtaposition and irony is eerie. Our speaker acknowledges that she is a money machine and that her body constitutes the common wealth. Stranger, though, is the revelation our speaker stumbles upon when she says: I’m late for the tour / where I’m a blooming black dollar sign. Even hundreds of years removed from chattel slavery, our speaker’s Black body, my Black body, and perhaps your Black body, is still monetized, is still seen as a price-point in the academy.

In the poem called “Happiness,”—a powerful crown of sonnets—our narrator juggles multiple truths about higher education, the commodification of students of color on scholarships, the financial servitude of having to use borrowed funds from the local and state government, from institutions acting not with the best interest of people of color in mind. Our narrator is educated, understands that she is in the history she writes about, that she is the bearer of the Free Smiths’ legacy. A part of that legacy is freedom, is the ability to move upon the earth as they moved upon the earth. But, like her ancestor’s, the speaker’s freedom, too, is bookended by whiteness. She is trapped in a different kind of commodification of her blackness, of what good her labors might produce for the benefit of the advancement of the academy. In the fourth sonnet, the speaker says I ate / the beautiful books I bought / with borrowed funds / and swallowed down / that two-ness one ever feels. / My body’s debt… Disturbingly beautiful, our speaker acknowledges that the bounty of her efforts produced within the academy will live longer than she does, like the few relics of her ancestors, the free Smiths.

A few months after the passing of Granny, I took a DNA test through Ancestory.com. The test was not for naught. Slowly, as weeks passed, I’d get an email here and an email there. Nothing of pressing matter. Then one day, I received a message from a distant relative, whose genealogical search on my maternal side of the family produced answers. She shared photographs of my ancestors from my Granny’s side of the family. In each grainy, sepia-toned image, you could make out a gap in the teeth of my ancestors’ smiles. And then, eventually, the photograph appeared that would prove a truth I always found to be evident: a distant, distant grandfather with a large pointed nose and blue eyes, sat next to a dark-skinned woman who would be a distant, distant grandmother—whose children would one day be relegated to a status of second-class citizen because of the one-drop rule.

In the United States of America, Blackness cannot be written about without writing about whiteness, without writing about witness. To witness one’s history, one’s identity bound up by the rhetoric of “white blood” or “black blood” is to spit saliva into a clear vial and send your DNA off to some laboratory to be inspected, to be given the answers you might have been asking yourself for years. White Blood: A Lyric of Virginia is a collection made of living things: from the cursive of historical documents rooted in racism to the messages our ancestors send to us; from the grappling we make of who we are in the present to the realization that our bodies are still commoditized. In White Blood, nothing is ever truly dead: not the results of a DNA test; not the remnants of one of the United States of America’s most racist and most powerful men; not the notes about the speaker’s descendants—Harriet and Butler Smith—whose ghosts live within the messages this text has, not only for Black Americans, but for all of us.