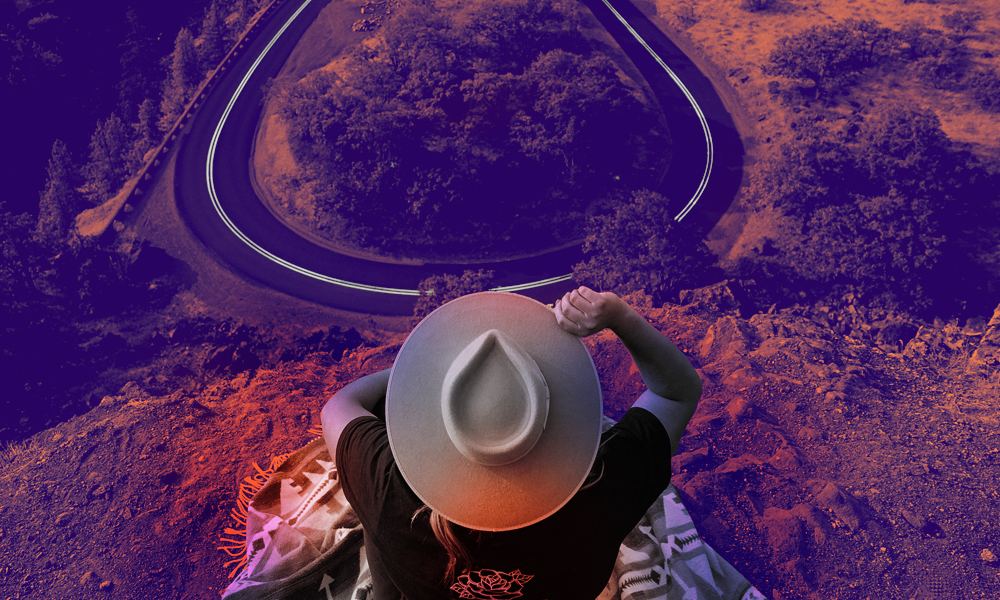

Night Drive

by Beth Meko

In those days, Lou and Harold lived down a long farm road in a little blue-roofed house tucked into the hills, which had been left to her by her parents. Harold worked midnights at the glass factory forty-five minutes south, and he would head out in the evenings, dust billowing around his creaking pickup truck as it disappeared down the rutted road.

After he was gone, the house belonged to Lou. She would open the console record player and stay up into the small hours, playing the records that had been her mother’s. In that dusty collection were great solemn orchestras, jazz that leaped and sparked like playful flames, solo piano that made her think of light glinting off shattered glass. She played all of them, feeling the reverberation in the walls, listening to them tell her things that didn’t have words.

When one record stopped she would hurry to put on another, because without the music all she could hear was the house creaking. Sometimes she was certain she would hear her mother’s halting footsteps or her father’s cigarette-roughened voice through the walls, although her parents were dead and gone.

Lou was only twenty-six, but she already mourned her life passing by. All she saw before her were meals opposite Harold slurping his soup, trips to the laundromat in Hazelton with the greasy coin slots and peeling linoleum, and days spent tiptoeing through the darkened rooms. In the late afternoon Harold would emerge from the bedroom, face crisscrossed with lines from the pillow. “You’re not the one has to bust your butt in that sweat farm all night,” he would comment when he caught her stifling yawns or napping on the couch. Harold wasn’t yet thirty, but he had taken on the defeated attitude of a man much older. They fought a lot. Once he punched a hole through the drywall in the bathroom. Once she broke a glass — took it out onto the back stoop and shattered it on the concrete. They were the unhappiest they had ever been.

Her dad’s old ‘55 Dodge Lancer sat beside Harold’s truck in the cinder block garage—cracked seats, mouse nests in the vents. It still reeked of unfiltered Camels. After taking it for a spin Harold had said the engine was about busted but the car had “good bones” and he was going to fix it up, get a few hundred out of it, but work hadn’t allowed him to get around to that or much of anything.

One night in August she went out and started the Dodge as the sun disappeared behind the hills. She didn’t know why. Maybe because they’d had an argument that day and Harold had laughed when she threatened to leave. “Tell me where you’re going to go and how you’re going to get there,” he had scoffed. He knew she was trapped there, and the knowledge sat sour in her belly.

The Dodge’s engine sounded like rusty parts scraping against one another but leveled off as it idled. She sat feeling it buck and sputter, sweat trickling down the back of her neck, then turned the car off. But the next night, she started it again and coasted out to the end of the driveway, brake pedal creaking. At the end of the gravel she thought she would turn around, but instead, she swung onto the main road. She drove around the rutted country roads, smoking, window down, radio on, and then she backed the car, revving and whining, into the garage once more.

After that she started to take it out further, edging into Unionburg, and then into Hazelton, where she usually only ventured for the laundromat and grocery store. Every time the same exhilarating feeling of freedom coursed through her, reminding her of the meandering walks she sometimes took through the woods behind their house.

Lou lost herself in thought on those night drives, music coming in and out of the static, engine lurching as she coaxed it down the sleepy streets of the towns and over the hills that rose up on the south side of Hazelton. Sometimes she parked the car up in the ridges and gazed at the town, looking at the lights, wondering about the people living in this house or that house. She made up stories about them in her head.

“Must have got you a job,” said her longtime neighbor Janelle, who came by the porch while Harold was sleeping one day.

“No,” said Lou, “it’s just Harold that works. Night shift over in Westfield.”

“Oh, I just see you leaving in that old car time and again around nightfall,” said Janelle. “Figured you must have you somewhere you need to get to.” Janelle’s eyes pressed.

Of course the neighbors would assume she was meeting a man — what else would they think? Word had a way of getting around, despite the distance between the houses. All it would take for Harold to be clued into her outings was a word from Janelle in passing. Boy, that wife of yours likes her late-night road trips, don’t she?

For months Lou abandoned her night drives, but she missed them. What was worse, the record player started acting up, letting out only a warped, dying sound, and even switching out the needle didn’t help. No more grand symphonies or jazz saxophone reverberated through the house; she had to settle for the television. She turned the late shows up loud; Harold would come home to find white noise billowing from the outdated TV set and her asleep on the couch.

The air turned colder. One Sunday in November she saw in the newspaper that the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra was going to perform a composition in January by a man named Brahms. She didn’t know anything about Brahms, but she recognized this concerto from her mother’s collection. The past summer she had played it over and over as she sat out on the porch smoking and watching the hills become dark shapes in the fading sunlight. The music was powerful and agile like a leaping tiger and had the feeling of eternity. It made her feel connected, all at once, to everything that had ever happened. Each instrument, the piano and the strings and the lilting flutes and low oboes, called out and answered one another to tell a story that had existed before her and was ongoing.

Lou, who had never been to a live symphony, ached to attend although she knew it was impossible. Harold would never go for it, and anyway, she didn’t want to see it with him. His ears were accustomed to the loud and expected, the clash of machinery, the buzz of saws. He wouldn’t enjoy something that commanded silence and attention; he would be bored and annoyed. She didn’t even ask. But she kept that page folded inside a Montgomery Ward catalog, and after Christmas she surprised herself by sending a money order and a return envelope.

It didn’t seem real until she received the little envelope in the mail with the gold-embossed ticket. She was going to take the Dodge into the city, an hour’s drive each way, after Harold left for work in the dead of winter.

Pulling it off was like being in a spy novel or one of those adrenaline-laced features they showed at the matinees. Harold left early that night, tires crunching over the driveway, headlights punching a narrow way through the plowed roads. She had been wearing her black sheer stockings underneath her pants all evening. As soon as his truck rolled out, she pulled on the forest green wool dress she had worn to her cousin’s wedding the year before and the scuffed pumps from her former temp job at the steno pool.

The air was sharp and cold in her nose as she started the Dodge. A plow had come shuddering through the night before, leaving snow drifts on either side like shrugging shoulders. Headlights off, she coasted the car down the middle of the slender pathway past the neighbors’ houses. As she pointed the car onto the main highway that would lead her into the city she felt excitement course through her, like a live cord running from her neck to the top of her legs. Surging forward in the sad old Dodge, she felt as if she were soaring—above the sparse lights of the winter-chilled farming community, above the road that rolled out like a dark carpet. The roads grew clearer as she moved further from the hollow, and then there she was passing the state sign, and the cord within her was glowing and alive.

It was the craziest thing, driving into another state all dressed up in the dark, heart slamming a tune inside her ribcage, while Harold worked with a sour look on his face back there in the fluorescent glare of the factory. For a second she felt guilty, and then she felt gleeful. She imagined the shock and rage on his face if he found out she was in the car on her way to the city. There was no way to explain it to him—she wasn’t sure she even understood it herself. Who does this kind of thing? she thought as she turned the wobbly knob of the radio, trying to find music through the static. She hit on some bluegrass and the fiddles cut sharp ribbons of sound that wafted out into the still night.

She kept on, nursing the squeaky gas pedal. She kept on, that cord running through her still hot as the music pulsed and the road widened, more cars appearing around her. She prayed the run-down Dodge wouldn’t die in the middle of the busy road. She thought, I could turn around and go home, but then a hillside loomed with a bright tunnel going through it, and there was no turning back. She was in the tunnel, in the guts of the hill, neck and neck with cars whooshing past, and then she came out the other end and there was the city spread out, tall buildings reaching to the sky, flamboyant lights splashed all around.

She parked the car in a massive echoing garage and ran down the street toward the beckoning marquee, breath floating in clouds. She stomped snow from her feet in the warm foyer of the theater, where a gold carpet led inside to a grand staircase. She could feel the curious eyes of the bow-tied man who took her ticket, of the usher who hurried her to her seat, the lights of the theater flickering and a bell sounding. Who was this giddy woman with a home permanent, shabby coat, and scuffed shoes, attending the symphony alone after dark in the city? She felt all eyes were on her but she knew in reality none were. The perfumed symphony-goers sat shoulder to shoulder watching the stage, and a hush fell around the room.

The conductor raised his baton like a sorcerer and she had a thought — Harold will notice the tire marks — and then she didn’t think about Harold anymore as the instruments rose their grand voices, their light insistences, their bass intones, intertwining together like wisps of smoke above their heads. She didn’t think about Harold, or much of anything else, as the music called to itself and answered, and called to something outside of itself. The music was a mad swirl and then became quiet, searching. It seemed to disappear as if behind a film of curtain but then it returned with new resonant layers. It rumbled, a thing gathering strength as it pushed forward.

All the way home, back through the brightly lit city and the quiet tunnel, she felt that cord of exhilaration running through her. It was enough to make her forget to worry about Harold seeing the tracks, although a fresh layer of snow ended up falling early the next morning and he did not.

♦

Harold was reassigned to day shift that spring and that was the end of the night drives. In May, he put an ad in the paper and ended up selling the Dodge for $350. A man wearing greasy coveralls came out and took the car for a test drive, then peeled off the money from a thick stack in his pocket.

“Glad that old junker’s finally gonna get some use,” said Harold as they watched the car disappear down the road.

In the months that followed, Lou took aimless drives through the farm roads after her weekly errands, groceries rattling in the passenger seat of Harold’s truck, radio turned up high. Other days, while Harold was at work, she wandered in the hills behind the house on foot. One evening, she roamed so far that she nearly got lost and had to stumble through a tangle of blackberry bushes down to the road as the sun lowered behind the soft slopes of the hills. As she made her way toward home, she admired the mauve sky darkening against the flame-colored maples and joyfully imitated the sound of an owl that had begun hooting from the tree line. Passing by Janelle’s house, she caught sight of the older woman watching her suspiciously from the small kitchen window that faced the road.

Lou felt a warm satisfaction even as she shivered in the cooling air, imagining what Janelle might say to the neighbors. I just don’t know what to make of that girl. Saw her wandering around in the dark last night with leaves stuck in her hair, screeching like a wild animal.

As Lou made her way toward the house with Harold’s truck parked in front, she finally answered the question that she had asked in the car that night in January. The thought would come to her even years later whenever she found herself doing something unexpected, whether it was writing a check for a new record player without consulting Harold first, or taking a spontaneous detour on a sunny afternoon, or wandering in the woods for hours until she could no longer see the little blue-roofed house at all.

I do, she thought. I do this kind of thing.

Photo credit: Karsten Winegeart