There’s a giant tree in Yosemite National Park with the insides carved out so you can drive a car through its center, and it’s still alive because trees grow from the outside and the inside bark was already dead when it was removed.

It’s a fact I recited on a stage in a poem at the College Unions Poetry Slam Invitational many years ago. The poem — not a very good one — was about my adolescent eating disorder and the man’s world that carved my young body empty. All of the years closest to the tree’s birth had been removed; her history started over when her carvers decided it should — whatever year made her hole big enough to accept the entry of a machine.

August 1, 1995: Tree Ring

Nineteen years and a day before Daddy died, I was a little over a year old. Grandma Erma had died; my family took her ashes up to Grand Mesa, rising between the Colorado and the Gunnison River and covered in little lakes. I was slathered in sunscreen, my tiny face a sheen of white. The lake alongside which we wandered was only symbolic of the place Erma went to ride her bike as a kid. The real lake had been turned into a dump, so the water body we chose was one whose meaning we invented. Same as a gravestone.

When Mom and Uncle threw the ashes out over the water of the lake, the wind picked up and blew them back to us, covering my sticky face in gray sand. I licked my lips.

“Grandma’s salty.”

I understood better than I should have.

I didn’t realize then that the fact from my old poem is actually a lie.

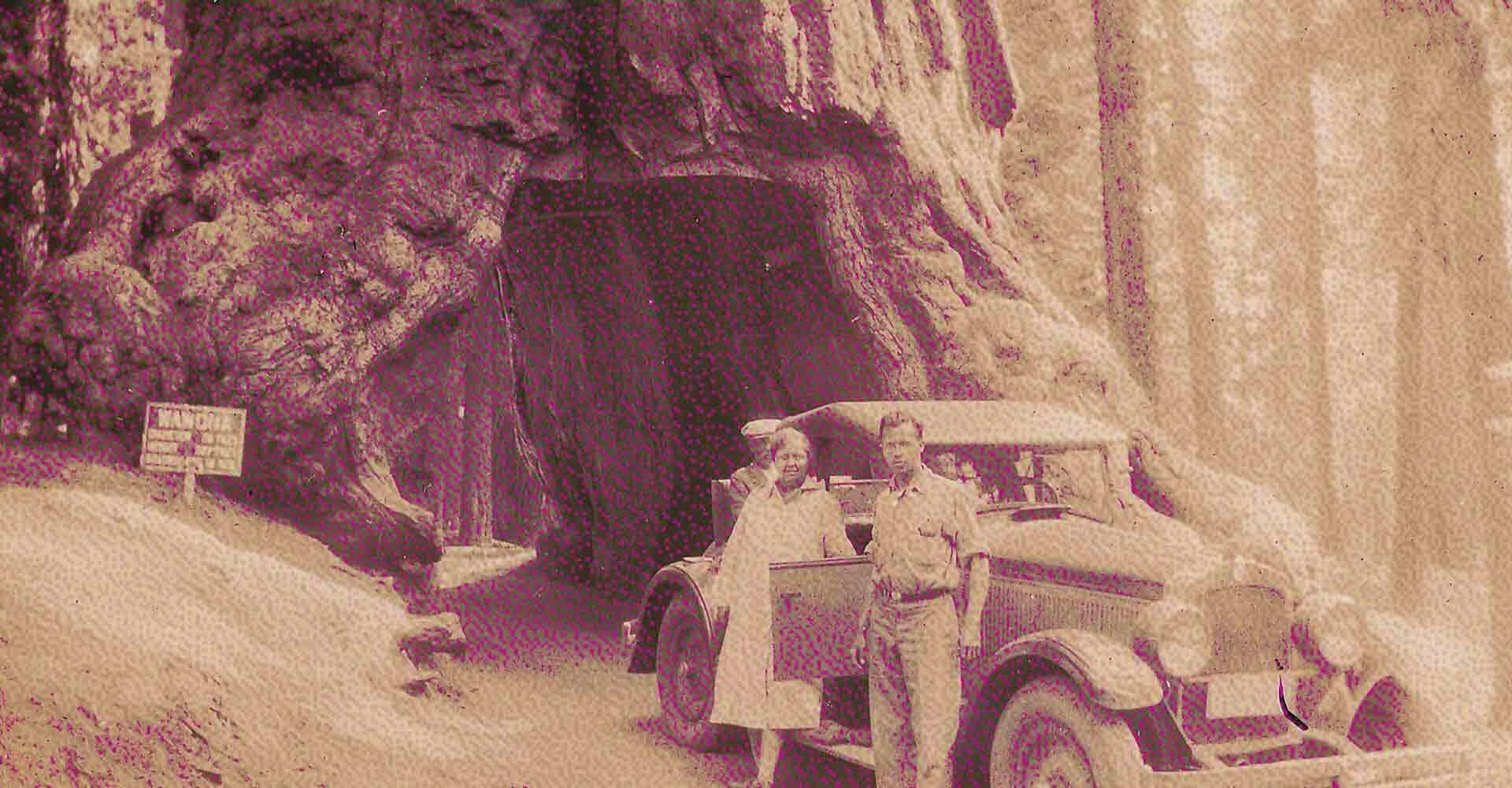

The first drive-through tree was carved from just the stump (albeit a truly massive stump) of a giant sequoia in Yosemite’s Tuolumne Grove that was, of course, dead; most of the tree was felled after it was struck by lightning. The charred and carved-out stump quickly became inspiration for similar mutilations of giant sequoias and redwoods throughout Northern California, which drew tourists first in stagecoaches and then very soon in cars as the automobile age launched in the twentieth century. The living tree from the poem might be instead the Wawona, the second of these attractions and the first originally carved in a living tree. The Wawona Tree was hollowed in 1881 and kept quietly growing for many years. But she too fell, in a 1969 snowstorm at a full twenty-six feet wide and more than 2,100 years old.

When I first wrote, I didn’t know she’d died. Chronology, narrative, gets muddled in the hands of people. The Wawona lived for eighty-eight years gutted of the rings of history closest to her beginning, and then she died because of the masculine carving that weakened her. (I think: Have you ever woken up, unsure of what a man did to your body while you were sleeping?)

The Southern Pacific Railroad and the Yosemite Stage & Turnpike Company pushed for the hollowing of the Wawona Tree after Yosemite was established as a public trust of the state of California in the 1860s — a designation to protect it from continued Gold Rush decimation and the first of such designations of land to be reserved for public enjoyment. Meanwhile, Miwok people who had stewarded the region for at least four thousand years were killed and starved by the thousands as white settlers chased the things they might take credit for protecting. The companies wanted the Wawona to bring coach traffic the twenty-five or thirty miles south from Yosemite Valley to drive through her in all her glory, years stolen from her history and made into carved trinkets to sell.

The hypocritical man who became the first director of the National Park Service in 1917 also made himself a millionaire mining borax in California’s Santa Clarita and Death Valley. Stephen Mather cut wealth from the ground and became well-known for his genius at marketing what he mined. Meanwhile, his well-matched business partner, Thomas Thorkildsen, lived lavishly and more than once had to dig the bodies of drowned elites from the garish divot of his heart-shaped swimming pool. His parties were known for their raucousness and booze, the diamonds of a couple unfortunates twinkling from six feet underwater while the rest drank on. Rings and rings and rings. Holes and holes and men, reaping.

(I’m trying to apologize to the trees.) (I’m trying not to let the rings be parenthetical to the story.) (The rings make the story.) (I’m here to study the story.)

August 1, 2006: Tree Ring

Eight years and a day before Daddy died, my family finally took Grandpa Frank’s ashes to spread; he’d died on Valentine’s Day. Before, he was in a coma or a daze for weeks, bedpan-shitting.

Grandpa loved to tell stories, and he loved even more to fill them with lies; kick the truth and watch it swell bigger. He wrote a family history before he died, printed three copies, one for each grandchild. Mom and Uncle weren’t allowed to read it — Grandpa held tight to his Once Upon a Times.

With the ashes, Cousin Two and Cousin Three and Uncle and Mom went up to Walsenburg, just east of the Sangre de Cristos, where Grandpa used to go target shooting. They threw his dustbody and grabbed rifles from the truck to fire off into the air. Turned a body to gun smoke.

My fact about the tree living wasn’t actually a lie. Or. Some version of it is true. The California Tree, a former drive-through and now walk-through tree still stands, alive, in Yosemite’s Mariposa Grove, but most of the internet thinks she’s dead because we’ve mixed her up with another. One travel site says, “While there are 500 giant sequoias in the Mariposa Grove, only the largest are given names,” as if, given a colonized name, she might be remembered. But many Wikipedia users, bloggers, and journalists alike mistake California for Wawona, saying she fell fifty years ago. I think of her when I fall asleep: disemboweled of years, made famous for living through the pillaging, and then narrated into a ghost anyway.

Scientific management of forests began, according to physicist and activist Vandana Shiva, when the British colonial powers in India appointed the first Conservator of Forests in 1806 to manage the felling of a massive number of teaks in order to build ships for the colonial efforts of the King’s Navy. Murder to create more murder; erasure for attempted erasure. Shiva coined the term ecofeminism to draw a clear link between violence against women and violence against the environment and to press against these wrongs. Both violences, she says, demonstrate a world that has “shorn the feminine principle.” The forest itself — the awe of a balanced ecosystem — is an example of the feminine principle.

Near the Himalayan foothills, where Shiva was born to a forest conservator and a farmer, the forest is worshipped as the goddess of life and fertility. But not the fertility of humans running wild, populating the earth with children, the very most environmentally taxing choice. The forest’s fertility is that of a whole system, sharing of itself to hold space for the gentle meanders and tugs of life toward continuance even when individual threads end. A queer fertility. A queer builder of family, of years and circular years of community. A willingness to let the dead be dead too: heterodoxy in the world of colonialism and imagined immortality.

Trees are not as metaphor or proxy here, but actual body. Body as body.

August 1, 2010: Tree Ring

Four years and a day before Daddy died, on a ranch in Rand, Colorado, my friends and I were just sixteen-year-old girls, driving four-wheelers over the acres and shooting at clay pigeons and glass bottles in the dump.

(When mortician Caitlin Doughty traveled to Áltima Funeral Home in Spain, where bodies are placed behind glass panes or in glass boxes for visitation, she concluded — “to understand the death rituals of Barcelona, you must understand glass.” She went on, “glass means transparency, unclouded confrontation with the brutal reality of death. Glass also means a solid barrier. It allows you to come close but never quite make contact.”)

My friend’s dad fixed our posture: stance perpendicular to the target, weak side in front. Shoulders rolled forward to manage recoil. We didn’t shoot at anything living. We just loved listening to the glass explode.

Vandana Shiva argues that maldevelopment — development which violates natural interconnected systems (development that’s “usually called economic growth”) — “becomes synonymous with women’s underdevelopment (increasing sexist domination) and nature’s depletion (deepening ecological crises).” Colonial dispossession and violence, of course, are epitomes of such violation.

(I think of Shel Silverstein’s The Giving Tree.) (The thoughts are worth mentioning, I tell myself. The thoughts build my years of rings.) (The famous picture book, a story of the tree who gives her leaves and apples, her branches, and eventually her whole trunk away to an ungrateful boy-turned-man who takes from and forgets her, has sold millions of copies.) (“And the tree was happy,” “And the tree was happy,” Silverstein insists over and over again as her body is carried away and put up for sale or used to build from.) (After the man cuts down the Giving Tree and builds from her trunk a boat in which to sail away from the world he’s built for himself, there is a moment — “And then tree was happy . . . but not really” — when the book could have ended truthfully. Instead, we learn that the tree is only unhappy to be forgotten and left by the man. In the end, the man returns to sit on her dead stump, “And the tree was happy.”)

(The man cuts her all the way down and another man writes her as a character who’s happy about it.)

(Do I need to say that I think of the years of light cut from the sequoia and redwood trees in Yosemite?) (History? Storytelling?) (Rings?)

August 1, 2013: Tree Ring

A year and a day before Daddy died, the two of us hiked toward the top of a 14,270-foot peak in Colorado with a friend of mine, whose own father had died a month before in Tulsa.

We hiked for a couple hours through bobbing hillocks strewn with big rocks and green. An insistent chipmunk begged for crumbs of anything when we stopped to lean on a boulder and sip from Nalgenes. There’s so little shade on the high-altitude Grays Peak trail that we didn’t stop for long — it’s easy to get sunburned and chilled at the same time, standing still in the mornings of the Rockies. I don’t remember what we said, if much. I’ve always loved hiking for the deliciously long and soft silences. When we hit the rocky switchbacks of Grays, my dad started taking a rest at every sharp turn to catch his breath. Another hour or two passed of everything looking more or less the same — jagged Vs cut in rocks and scree — and he came to a complete stop.

“I think this is it for me, guys.” His voice was light-hearted but turned down at the corners, his shoulders hunched around him.

When my friend and I summited less than five minutes from where my dad had stopped, I scrambled back down to him, thrilled to draw him out of turtling defeat (a sense both that he’d failed and that he was unable to remedy the failure).

Step by small step, we climbed. The trail gets so steep in places near the top that I was often a full three feet above him, my whole torso over his head, even only a step or two in front of him. Then, together, we came to stand on the same ground. That was what I noticed before I even looked up to show him he could do the same. Dad and me, pinking-shear ranges of mountain tops in every direction.

Although we didn’t know it, he already had advanced kidney cancer when we finally stood together at the top of the mountain that shared his name. The hardest physical thing, he said, that he’d ever done. The first European to climb Grays named the peak for Asa Gray, a famous botanist who added his own theistic twist to Darwin’s ideas. The Arapaho nation, though, called the mountain and its neighboring fourteener heeni-yoowuu, which translates to “the Ant Hills.” A climb humbled by scale.

From the peak, my dad had a year to live.

In February 2015, at Western Carolina University’s Forensic Osteology Research Station (FOREST), Katrina Spade placed her first human composting donor into a pile of wood chips at the base of a hill. Spade started considering body composting while in a Master of Architecture program at the University of Massachusetts Amherst in 2011; she was reflecting on the environmental costs of cremation and traditional burial, which are significant. A decade later, Spade runs Recompose, an organization dedicated to ecological death care and helping people genuinely return their bodies to the earth when they die. In 2019, Washington became the first state to pass legislation approving the composting of remains, followed by Colorado and Oregon in 2021 and Vermont in 2022. California and Massachusetts are making efforts to do the same.

Spade and her team covered the first body, a seventy-eight-year-old female who died from a drawn-out illness, with alfalfa and wood chips and wrapped the mound with a wire fence. The team added buckets of water, both science and ritual. A locust tree stood proudly at one end — a living memorial and hopefully a recipient of the rich soil the body would produce.

I find it a deeply feminine process, this of returning the self. Perhaps it’s just antithetical to the theft of bodies that feels both so colonial and so mired in a detrimental masculinity. The commensalism (or perhaps even mutualism — if the humans who live on can learn anything from the effort) in the dissolution of a body into nutrients in the soil threatens systems of patriarchal power. Of course it does. Those systems depend on individualism, domination, conquering — all in an effort to make the one eternal.

Colonial manhood seeks to carve its name into other bodies, to leave evidence of and reproduce itself. This longing for immortality is also what makes the carving out of the trees’ rings of time a sexual theft. An action done to the bodies of the forest in order to produce wealth for men. Lamenting a friend’s claim to ownership over trees that burn, Southern Ute writer CMarie Fuhrman decries “the assumption that anything natural is only beautiful in what humans have decided is its most productive state.”

A nod to the cycling of the land, near to the arrival of menopause, Fuhrman writes of taking her menstruating body to the Frank Church Wilderness in her home of central Idaho:

“I have found it very natural to come to the woods during my menses. Movement has always quelled the pain and the ability to find a rock or stump on which to sit upon while my uterus sheds its layers, while my body completes another cycle that female bodies — human and not — share, is somehow comforting, communing.”

But instead of bending in the gentle direction of release and decay, the direction of the natural, we of the colonizing and industry-driven world go around carving the histories out of the trunks of 2,100-year-old trees so that we can drive machines through their empty guts. Experience something, leave a mark. Of course, harmful acts done in order to affect are noted more often than beneficent acts or nurturing acts or acknowledging ones. Perhaps this is because the natural world is so generous and generative; harm is the thing that creates a stark contrast. Perhaps it’s because mostly we live in a world of narrators who don’t view the carving of the Wawona and the California as “harm.” (And the tree was happy, I think.) (That’s the way we tell the story.)

August 1, 2014: Tree Ring

The day before Daddy died, I rear-ended someone on Arapahoe Road in Denver, driving back to Mom’s house after spending a mundane day with him. I was stuck in stop-and-go traffic, crying. The woman whose car I hit was blonde, with curls. We both used her pink pen to take down each other’s information.

That day, Daddy looked worse than he had since a hospitalization months before. His head, too heavy for his neck, seemed to rest only on his shoulders. When I left him that afternoon, I hugged him a long time.

He called a couple hours after I got home that night. I was sitting in the front yard with the dog — using the grass and darkening air to cool us both; Mom’s rental had no air conditioning. The streetlights were beeswax-glowing, even as blue clung to the sky. The insurance company had called him, and my dad was livid (that I hadn’t told him and that I got in an accident to begin with). He accused me of texting while driving and pleaded with me to pay attention to what you’re doing. (I wasn’t texting.) (I was crying.) I threw mental darts at the blonde woman, whose car was completely fine and who’d told me she wouldn’t even call the insurance company. I felt my information, in pink pen, flying into a world over which I had no control.

A friend suggests that maybe it was good for my dad to feel like a parent again for one night — the empowerment of that — for the first time in months. There was so much strength in his voice then, strength I was training myself to forget existed in him. After the lecture, he said I love you. I mumbled mhm and hung up. That was the last time I spoke to him.

(I can hear an environmental activist in my head — he’s telling a story about another activist who insisted that the financial protection the first provided for a section of old-growth forest was useless. “But how many of those trees did you plant yourself?” the second man asked. As if growth and continuance are only useful when a human can take credit for them.) (I think of the world we’re supposed to make for our children, those children we’re supposed to have. Our little mirrors, who make us immortal.) (“Why do I need to plant the trees?” the first man is responding. “Why is protecting standing forest not as good as recreating a forest who has been destroyed?”)

The first man is right; anyone not out for fame and a slap on the back can see so. He’s taking the tack of a preservationist, an activist or environmental theorist or a lover of the planet who believes in guarding and protecting land, for the most part, from human touch or from the touch of industry. He’s saying: protecting what’s here and calling it sacred without expecting anything of it is a worthy cause. (Of course, humans get plenty from the intact existence of old-growth forests, but that’s perhaps beside the point.)

Another camp of environmental advocates and stakeholders, conservationists, instead take sustainable use as their focus. These are the loggers and fish and game folks and ecotourism groups and plenty of activists who think preservation is a lost cause. Perhaps the second man from before is a conservationist — advocating for replanting in a sustainable logging cycle.

I fall on the side of preservationists, generally, but I’m not foolish enough to believe it’s wholly possible with a population so over carrying capacity and without other major economic changes. Still, I believe that to forget the ideal: that natural ecosystems are inherently worthy of the space they take, unmolested — that they have knowledge humans can’t begin to fathom — is catastrophic. Many preservationists have forgotten. Derrick Jensen, the activist from the earlier conversation in my mind, has forgotten, as evidenced by his commitment and recommitment to transphobia, imagining that a patriarchal construct of gender essentialism, a human construct, can “save Mother Earth.” The man turned himself into a gender warrior, using small-minded rhetoric to erase the expansive possibilities of nature and to turn the earth into his princess locked in a tower, all in one swoop.

(I think of the men, again, coring majestic trees, trees born before their God — God of domination and God of oversimplification — the men who coddled themselves with the label of conservationists as they brought hordes to Yosemite in the early years of its “protection” to applaud and hand over some cash and the preservationists righteously coddling themselves and barring the doors to environmentalism with ill-conceived and hateful green fundamentalism.)

In contrast, when Caitlin Doughty went to investigate what Katrina Spade was doing with donor bodies in North Carolina, she wrote of the people “changing the current system of death”:

“The main players in the recomposition project are women — scientists, anthropologists, lawyers, architects . . . Katrina noted that ‘humans are so focused on preventing aging and decay — it’s become an obsession. And for those who have been socialized female, the pressure is relentless. So decomposition becomes a radical act.’”

Further, decomposition becomes an act of removing human constructs from the wisdom of the natural world — preserving and valuing knowledge of how to take something apart with grace.

After-death care shifted, as Doughty writes, from being “visceral, primeval work performed by women to ‘professional,’ an ‘art,’ and even a ‘science,’ something with sharp edges, performed by well-paid men.” The industrialization of such care came with the spread of false information that bodies are dirty and infectious, things to be made pristine. Bodies are not. We’re not machines in our mortal lives, and there’s no need to continue the charade in death. (When I was caring for my dad, when I was grieving him, I kept trying to make boxes to check and check them — legal pads and their lists everywhere — trying to get things right.) (Years keep going by and adding their sweet rings around me.) (The story keeps changing.) (The truth keeps changing.) (The truth is not industry or machine.) (Not a line, but a body.)

Some of the August 1sts didn’t happen on August 1st. Many did. Maybe we spread my Grandma Erma’s ashes on that day, a month after she died; it’s likely we waited a year and spread them the next summer when I was two. Maybe it was August, maybe June or July. It’s hard to know when glass bottles were shot to glitter. I have always wanted things to line up exactly — it’s the straight lines in me. The Bible I spent my high school years learning says man looks like God and woman looks like a rib bone. (I think of the gentle C of my dad’s rounded shoulders.) I don’t know what we’d do if something curved — decay or queerness — turned out to be godlike.

Of course it was a queer woman who put a body at the base of a tree in a sea of woodchips to see if the old dead woman might feed herself back to the dirt. This is queer fertility, collecting back the circles of the story.

(Undoing the theft of girlbodies.) (Circling the beginnings.)

Excerpts are from the following:

“Visiting California’s Mariposa Grove: 9 Things to Know” from TravelAwaits.com

Staying Alive: Women, Ecology, and Development by Vandana Shiva, Zed Books, 1998

From Here to Eternity by Caitlin Doughty, W.W. Norton, 2018

The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein, HarperCollins, 1964

“Grays Peak” from The Armchair Mountaineer

“Lake 8” by CMarie Fuhrman in Platform Review, September 2020

The Myth of Human Supremacy by Derrick Jensen, Seven Stories Press, 2016

Image credit: Chetkres