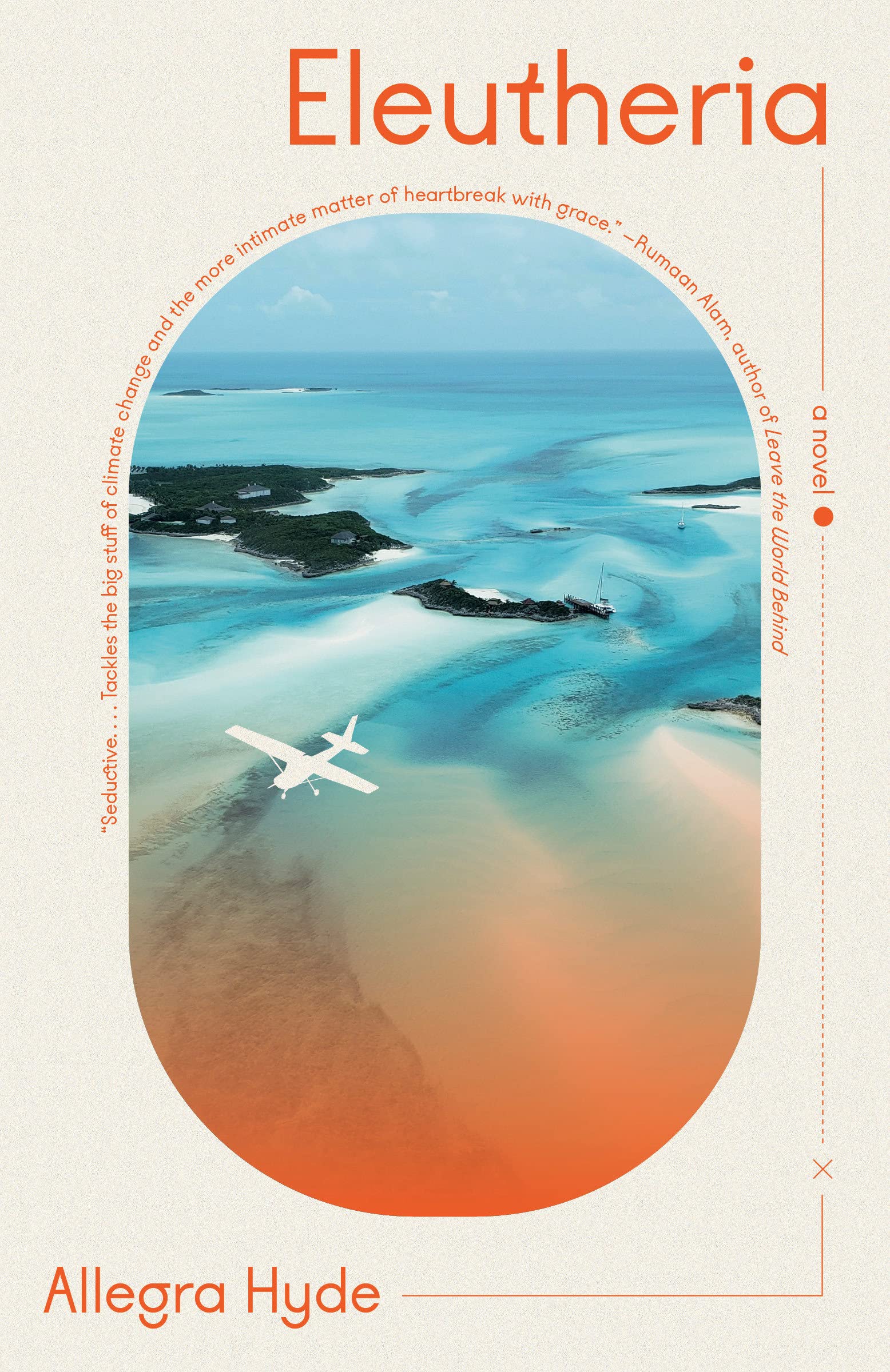

Allegra Hyde is the author of the novel Eleutheria, as well as the story collection Of This New World, which won the John Simmons Short Fiction Award through the Iowa Short Fiction Award Series. Her stories and essays have appeared in The Pushcart Prize, Best of the Net, The Best Small Fictions, and The Best American Travel Writing. Originally from New Hampshire, she currently lives in Ohio and teaches at Oberlin College.

Click here to order Eleutheria, available now from Vintage!

Where and when was the first kernel of Eleutheria born?

The kernel materialized over a decade before I finished writing Eleutheria. I visited the Bahamas for an environmental research project in 2009, then returned for a human ecology fellowship in 2010. The more I learned about the cycles of idealism and exploitation that had occurred there over the centuries, as well as how an island like Eleuthera was, in a roundabout way, connected to New England — the region where I’d grown up — the more it obsessed me. Here was a small, remote place that was dense with human history, loaded with contemporary significance. I remember biking out to a rocky cliff on Eleuthera and looking at the ocean and muttering sentences under my breath about the history of the place: Columbus arriving and abusing the indigenous residents, Puritans showing up and thinking they’d found paradise, pirates circling the coves. The resulting novel (which followed a short story also engaging this material) is not an effort to speak for the Bahamas in any way, but it is an attempt to contextualize how a crisis like climate change connects people and communities across time as well as geography.

Eleutheria swings between the present-day narrative of Willa’s time at the Camp Hope settlement, the events that led to her interest in the camp, and a history of Eleutheria. Can you tell us about the process of writing these various threads and how you fit them together?

The writing process was chaotic — at times maddening. Writing short stories has always been intuitive for me, but drafting a novel felt like a whole other animal, one that I wrestled with for about five years.

What I can say is that I started by writing islands — an idea I learned from Matt Bell. I drafted disparate scenes, concepts, character sketches, in an effort to generate a lot of material that I could later shape. Then, slowly, slowly, I teased these islands into more coherent narratives. Occasionally, I tried outlining, but ultimately it was a process of painstaking trial and error — with lots of errors — as I tested different character traits, decisions, and outcomes. The thing about editing a novel is that if you change one thing, a butterfly effect occurs — the change ripples through the whole manuscript. So that makes it a slow process.

Once, however, I started to really understand my narrator — Willa Marks — understand her motivations, her goals, the shape of the novel came into focus. I understood how her past was a current running through her present. Meanwhile, the historical interludes — describing the colonial progression on Eleutheria — moved around a lot, but I always knew I wanted them to be the spine of the novel. That historical thread would thematically underscore what was going on with Willa, with Camp Hope, while also offering a perspective that Willa simply couldn’t provide, given her particular point of view.

I love the idea of using trial and error as a drafting technique. That must require a lot of patience and trust in the process, knowing that not every thread you follow will ultimately work out. What do you think you gained from this method that you would have missed through outlining?

What’s funny is that I did try to outline, periodically. I would break the novel into proposed sections and then diligently craft a synopsis for each section. I wrote out descriptions of characters, too, trying to understand each of them better. I tried mapping out the novel over and over, and while this helped me hold the whole book in my head, my proposed trajectories for the book never quite worked on the page. They felt too wooden, too mechanical. They didn’t quite make sense in a way that evoked genuine emotion. The only thing that really worked for me was letting my sentences guide me, which is another way of saying that I had to listen to my story closely. Maybe there wouldn’t have been so much trial and error if I’d been able to listen better sooner. What I do know is that when a plot point clicked on the page, I could always tell that it was the right direction to pursue. I’d be like: of course that character would do that thing! Maybe this sounds too mystical, but I had this sense while writing Eleutheria that there was a “true” form of the novel, if only I could find it. Drafting was a process of listening and searching and trusting that the novel was waiting for me if only I kept trying.

It sounds like you already had a lot of experience and background knowledge on your subjects going into this novel. Did you end up doing much new research? Did your research ever take you down surprising paths?

I did a significant amount of research, delving into topics that were wide-ranging, often esoteric. Sometimes I’d study types of tropical fish; sometimes I’d disappear into a rabbit hole of different types of curtains; sometimes I’d spend weeks reading and notating the trajectory of Bahamian history; sometimes I’d watch hours of doomsday prepper videos on YouTube. You’re right that I came to this novel with some background knowledge, but even on topics where I had firsthand experience, I often wanted to go deeper. For instance, though I’d previously spent time dumpster diving and interacting with a Freegan network — participating in communal dinners and free food giveaways — I still interviewed a dumpstering advocate and staked out locations around Boston where a person could scavenge free food, furniture, clothing, and more.

I learned the most with regards to strategies for activism. Micah White’s The End of Protest: A New Playbook for Revolution truly changed my understanding of what contemporary activist efforts can mean. Another book I found really useful was Earthforce! An Earth Warrior’s Guide to Strategy by Paul Watson. Watson’s book is three decades old, but it still has so many compelling points to make about “Eco-Guerilla Activity.” Those are the texts I still think about the most, especially as our climate crisis continues to intensify.

Eleutheria engages with the complexity of environmental activism and those who take the lead in these efforts. Has your relationship with activism changed throughout the course of writing this book?

I went into writing this book with a vague sense of something being off about a lot of the environmental activism I encountered. This was first with regards to the whiteness and privilege that often seemed tied up with environmental leadership. Environmental activism must, in my opinion, go hand-in-hand with social justice efforts; it must be integrated into the project of dismantling power structures and in service of creating more equitable societies.

The sense of off-ness was also connected to the ineffectualness of many activist efforts—despite the commendable dedication and diligence of their organizers. Take the People’s Climate March in New York in 2014. This was a huge march — the largest collective action to date — and yet it had little impact on environmental policy. I’ve come to believe that marches and sign-waving won’t work in the way they might have for movements in the past, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t other strategies, other ways of pressuring those in power. I just acquired Andreas Malm’s How to Blow Up a Pipeline, for instance, and it has given me a lot to think about in terms of escalating activist tactics. And as I previously mentioned, I still return to texts like Micah White’s The End of Protest. I find inspiration in White’s idea that social change can be rapid, but that it can also be a slow process that unfolds over centuries. Long-term justice, long-term equality, long-term sustainability: these are projects that may take generations to come to fruition. This means that some of us must be stewards of ideas, of knowledge, of seeds both literal and figurative. In other words: to be a teacher, a librarian, a gardener — that’s activism too.

Your first book was a collection of short stories, which also explored themes of utopian societies and environmental activism. What was it like to shape these ideas into a longer form?

Exploring these ideas in a novel form allowed me to push scenarios and ideas further. It’s not just What if this happened? It’s What if this happened — then this happened — then this happened? In Eleutheria, I started with the question: “What might it take to truly mobilize against the climate crisis on a mass scale?” The roominess of the novel form was essential for investigating multiple answers to that question, and to putting those answers in direct conversation. I could talk about Freegans, militant environmentalists, and youth activists — all in the same narrative. And because of the roominess, I could talk about doomsday prepping, academic passivity, and Green Republicans as well. The stories in my collection, Of This New World, might have been in conversation in their own way, but a novel makes the conversation more apparent. Interconnections, contradictions, stakes, are all more visible. Characters move across time and place, and, hopefully, take readers with them.

What I love about Willa is her stalwart optimism that often contrasts with the attitude of other people in her life. What do you think is the utility of hope during times like these, when we are inundated with so much bad news? No pressure — but what gives you hope?

You’re right, we are inundated by bad news. Stories about melting glaciers and school shootings and the erosion of democracy are unrelenting. The media cycle and our access to news only makes this sense of inundation worse. The danger, in my mind, is that this constant exposure to bad news might cause us give up. In the face of so many depressing updates and seemingly insurmountable challenges, it is easy to feel despair. It’s easy to throw up one’s hands and think: there’s nothing I can do, so why even try? But things are never going get better unless we try. Our world won’t become more environmentally sustainable, more equitable and just, unless we believe that it can. In my mind, the first step is maintaining a sense of hope and possibility. Because if you can hold onto that, then you can start to see all the ways that people are working so hard to push back against the entrenched political and economic systems that have helped create so many crises. You start to see places where you can contribute too. “Everyone has their own sphere of influence,” an environmental studies teacher once told me — a sentiment I’ve always found to be a source of hope. However large or small that sphere of influence may be, we each have the capacity to make a difference.

What advice do you have for other short story writers transitioning into novel writing?

Every writer is going to have a different experience, but for me, when writing short fiction, I could rely on voice and language to carry a piece. When writing a novel, however, I couldn’t rely on those tools alone; I needed a substantive narrative engine. This meant strengthening my understanding of plot mechanics. I read classic craft books like E.M. Forster’s Aspects of the Novel, as well as contemporary screenwriting texts like Screenwriting is Rewriting: The Art and Craft of Professional Revision by Jack Epps Jr. I learned so much. I try to push myself to develop new skills when I embark on new writing projects, which is why my main advice for short story writers — or any writers looking to venture into something new — is to be willing to continue learning. I think the most meaningful creative projects are the ones that challenge us to grow.

Other than stories, what are you creating these days?

I create a lot of teaching material! For me, teaching often means reverse engineering a writing process: finding ways to help students understand different craft techniques, and access their own imagination in new ways. Developing writing prompts and exercises is, for me, often creative act. I ask myself: How can I challenge my students — currently all undergraduates at Oberlin College — with a set of parameters, questions, points of comparison so that they’ll develop as writers and artistic thinkers? It’s like creating a puzzle: finding the right balance of possibility and difficulty. I never know quite how students will take to the puzzle, what they’ll do — but that is, of course, one of the pleasures of teaching.

What is next for you? Any spoiler-free sneak peaks?

I’m really excited to be putting out a second story collection next year. Titled The Last Catastrophe, it is mostly speculative, and, at times, satirical and absurd. Some of the pieces are already published, like “Endangered,” which imagines a world in which artists are held in captivity like endangered animals. And others have yet to be revealed, like a novella called “The Eaters,” which is about vegan zombies. I can’t wait to share!