Angelica, my roommate, invites me to hold babies at the local hospital as part of her class project, but not just any babies—opioid spawns—babies that shook from drug withdrawal, their tiny bodies in the blankets, vibrating. Dolls with cone-shaped heads. Small socks and even smaller socks. How sweet. I can just envision one of their little feet warmers straddling the tippy-top of my finger.

“It’s for one night, Ruthie.”

“If you say that, it means it’s for more than one night. You’re just not interested in my declining the offer so you’ll sweeten the deal ’til I’m stuck with it,” I say.

“They’re babies,” Angelica says. “Like goldfish, but larger and not under water.”

“Do they pay cash?” I ask.

“Learning how to nurture is payment enough.”

“I’ll think about it,” I say.

She seems satisfied and walks to the back of our apartment towards the kitchen. I’m on the couch in front of the television, shoveling mounds of cereal into my mouth. The milk dribbles down my chin while the noise from the Rice Krispies interferes with the television. I turn the volume up. I’m trying to watch the Bachelor. I imagine myself getting a rose from a man who is also seeing eleven other women, one of whom I can and will talk shit on when the cameras aren’t rolling; that’s what I would do if I were ever on a reality television show about love.

I still haven’t decided if I’ll go or not, but I fall asleep thinking about children.

♦

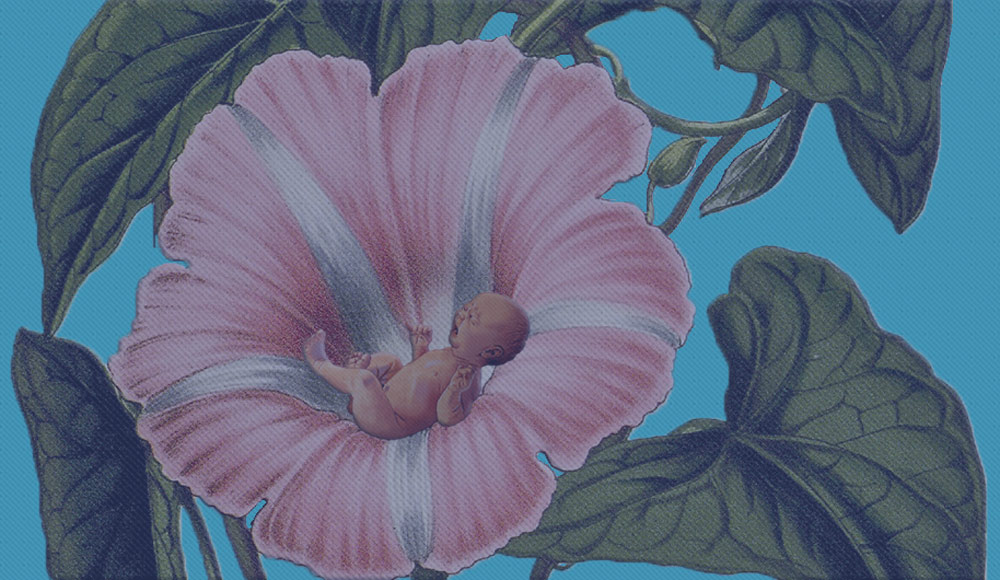

Inside the nursery, the infants all lay in their mangers, cowering from the ceiling lights, shrieking for something that’s warm and attached and full of milk. I peer over the edge of one of the plastic sides into the terrarium of an alien: big nostrils, tiny mouth, thin eyebrows, long lashes, plum colored skin.

Looking at it, I think of the time I read Bloodchild. The book was my dad’s whiskey coaster. I don’t know where it came from. But it was a love story in which an alien race impregnates the human son of her host’s family to continue her lineage. They called it a symbiotic relationship, but I can’t help but think that one of them was losing out. I imagined those grubby worm-children and how they would’ve looked in this antiseptic world. Their bloody bodies taken fresh from the cavern of a man’s stomach. Doesn’t seem far from reality.

A man wearing a mask approaches me. “What’s your name?”

I look down at the name-tag I grabbed off the welcome table. “Volunteer 8.”

“Take your shirt off,” he says.

I hesitate. I wore my ugly bra today. This isn’t fair.

“It’s to give the babies more warmth,” he says. In his outstretched hand is a crepe gown. Yellow, the saddest color if you ask me.

“You have to hold its head in the crevice of your arm,” he says, miming rocking a baby.

I nod because I cannot think of what words to use. The first baby he hands me, I do it all incorrectly. I look like I’m holding a loaf of bread. Its head jerks back to a dangerous angle.

“Careful!” he yells, taking the newborn from my arms. “Didn’t you take the class?”

“Uh, yeah.” He ushers me over to a small crib with a baby with tubes coming in and out of its body. I settle down into a chair with my arms out. I feel like I’m about to receive the baby Jesus. I wish I could record my face.

“This one’s Splenda,” he says.

“Like Brenda?” I ask.

“Exactly. Her mother’s been in here with four other children. I’m not sure where they’ve gone.”

“Why is her name Splenda?” I ask.

“Beats me, sweetie,” he says. “Give her whatever you have to give. They’re not picky.”

Splenda lays in my arms and she shakes. She shakes like she’s cold but there are so many blankets around her body that I couldn’t imagine there’s a draft. I hold her tighter. I want to keep the warmth inside. I detest being cold. She cries into my shoulder and into my chest. No matter how I hold her, she cries.

After forty-five minutes, one would think Splenda would calm down. But she cries more and more. I sit there for a while. Then I think moving around will help her more. I jiggle her up and down. All this does is make her diarrhea all over my gown.

The nurse brings over a blue suction cup and suctions the baby’s mouth. Then she changes the baby’s diaper. The circumference of the fattest part of her thigh looks like my wrist. Ten sizes too small. The new nurse gives Splenda back to me once she’s changed and I try to remember nursery rhymes from my childhood. I give up when none come to me.

“Isn’t this cool?” Angelica holds her baby up for me to see. Its face is squished up and angry. “This is Sheraton. Like the hotel!”

“Yeah, cool,” I say.

♦

A week later, while at the bank, I think about Splenda and how fast her heart beat against my chest—a hummingbird inside of her. I think about Splenda’s wrinkly skin and how much she reminded me of a raisin. She had tape over her eyes so I didn’t know if they were blue. I imagined her six years in the future, playing on a swing set.

At my teller window, using my work computer—which is against policy—I look up pictures of babies addicted to opioids. They don’t look very different from normal babies that I can see, but I haven’t had much exposure to normal newborn babies, only the ones at the hospital. I don’t have much to go off of.

There are some articles attached to the pictures that say often times the mothers don’t understand. How can’t they understand? What the mother takes is given to the baby. This is basic sexual education class. Then I see the statistics that most women who have opioid addicted babies dropped out of high school. I think, Great. Fabulous. We’re ruining ourselves from the minute we’re born in small towns.

I then google, ‘can you adopt babies addicted to opioids?’ I find a couple good articles and e-mail them to myself.

Because I’m not paying attention, I hand the person at my window a one hundred dollar bill instead of a twenty. This upsets the balance of things at the bank and I refuse to come forward. At the end of my shift though, my boss who is also my step-dad signals me into his office. I think what if he wants to fire me? I really didn’t want to lose my job. I could fake sick. Maybe jump out the window. Land on all my feet?

When I step inside the threshold, Gary’s face is uncomfortable. He smiles a little like it hurts to look at me.

“Close the door, please.”

I do so as slowly as I possibly can. I’m making my minutes count for something. I know what’s going to happen. Or at least I think I know.

“We’re going to have to let you go,” he says. I would be angrier if Gary wasn’t my stepdad and he hadn’t told me this might be coming two weeks ago. I’m just not good at keeping jobs. I get lost sometimes. I don’t know where I’m supposed to be. I think too much. I’ve told many people about this problem I have, but they tell me it’s because I’m too smart. I think that’s just an easy answer and they want me to leave them alone.

“Thank you for your whole four months of service,” Gary says. “Also, your mother would have wanted us to have dinner together tonight.”

“Can we order pizza again?”

“Sure,” he says. He knows I won’t go and he’ll drink a beer and I’ll see him around.

♦

At home, restless energy manifests into me baking unwanted delicacies—lemon bars and baked Alaskas and cereal bars with dried strawberries. I cannot stop no matter what I try. I think taking a break and locking myself in the bathroom will help. All there is, is the babies. The baby with the fat lips. The baby who cries when you put him down. And the baby who shakes so violently his oxygen has to be monitored. All their little ankle bracelets and they’re not even teens.

Angelica intercepts me on the way to the bathroom. “Will you go back with me?”

“I need to pee,” I say.

She holds my face between her hands. I think she’s going to kiss me. I picture dead frogs. The heat inside my body subsides.

“Just say you’ll go back with me.” She squishes my face together. The inside of my mouth tastes really bad.

“Fine. Now move,” I say, “or I will pee on everything you love.”

I spend the rest of the night sitting on the toilet, scrolling through How-To’s on being a mother. I clear my browser history then look up the best way to make blondies. For my own protection.

♦

Angelica’s so excited to see the babies. And I get it. She feels wanted. But mostly I’m sad that I’m even wanted in the first place. For this to be a volunteer position says a lot about this little city.

All there is, is the babies. The baby with the fat lips. The baby who cries when you put him down. And the baby who shakes so violently his oxygen has to be monitored.

“They call it NAS,” Angelica tells me while rocking her baby—Phillip—back and forth. She soothes his aching cries and rubs his little cheek.

“What’s it stand for?” I ask, giving a bottle to Splenda.

“I don’t know,” she says.

I think about taking little Splenda home with me for an hour or two. Then I remember I can’t just put it back when it becomes a hassle. They are good in these walls because we’re here. The moment I bring her outside, she’ll make me hate her.

“That one just threw up on me,” Angelica says. “Need a ride home?”

“Nah, I’m gonna stay with her,” I say.

When Angelica leaves I try to tell Splenda a fairytale, but I forget how it really goes. I tell myself I will leave when she’s asleep. I start to recite to her Bloodchild. The only thing I knew by heart.

“You will live now.” I wipe at the baby bubbles forming at her lips. “Yes. Take care of her, my mother used to say. Yes.”

♦

This visit, I’m alone. Angelica said that she had some missing assignments to catch up on for her English class, which I happen to know she finished last semester, but I didn’t pressure her. Us grown ladies can make our own decisions. Hers just happens to be wrong.

“It’s volunteer 8,” the nurse with the mole on both cheeks says. She’s the one who buzzes us into the nursery. She thinks I haven’t noticed the moving mole. I shrug my sweater off, thanking myself for wearing a cute tank top, and pull on the paper dressing.

When I walk into the room, I spot Splenda. She’s making the squealing noises and I’m full of something I can’t quite name. I’ve been choosing Splenda because she deserves the most love. It must be hard to be so new to such a cruel world.

“Babies are magic,” I say, rocking Splenda to the rhythm of a song I think my dad used to sing, but I could be mistaken. It might have been my neighbor. My utterances seem to linger in the air. Splenda’s body rolls along to my voice. I feel the urge to call my mom or someone’s mom if mine won’t pick up.

I drag my finger over the peach fuzz on Splenda’s perfect forehead.

“My mom didn’t love me either,” I whispered to my swaddling saint. Her eyes droop and I know she’s just about to fall asleep. But a monitor to my right wails. The alarm on the top flashes blue. The green flattens itself out—technicolor nursery.

“Code Blue! Code Blue!” the speaker warns. People rush forward out of the walls. A man in a coat pushes one finger in the center of the baby’s chest, then leans the baby’s head back to give it some air. The baby stops shaking. I swear I see it finally smile.

Who cries for these babies? I hold my breath. I picture sidewalk art and Christmas hams.

As I leave the hospital, it rains. How cliché, I think. But it makes me feel good about my life. Then I remember the funeral for my aunt Susanne. She’d been drinking at a bar before five and on her drive home she was hit by a tractor-trailer carrying chickens to a slaughterhouse. I read her a quote from the book Slaughterhouse-Five. She loved Vonnegut more than Stella Artois. I could be sentimental if the situation arose.

♦

At home, I cradle a loaf of bread. When Angelica walks in the door, I throw the bread on the floor then stoop, pretending to pick up the fallen slices.

“Where’ve you been?” she asks, laying several bills on the Formica.

“Here,” I say motioning around the kitchen. I pick up a sponge and rub the same spot on the counter erratically. “Cleaning.”

She cocks her eyebrows—her special talent. We all have one, she informs me. I tell her I haven’t found mine just yet. She says give it time.

“Why’s the bread on the floor?”

“It’s windy out today.”

She opens the fridge. I don’t think she believes me, but she doesn’t have to for me to be satisfied.

I say, “I’m gonna go to the bar. It’s Tuesday—they have bingo.”

“When I was little, I was confused if Bingo was the game or the dog.”

“Both,” I say.

“It can never be both,” Angelica says, then chugs milk straight from the container. I close the door, cutting her off. I hate when she does that. Also, it most definitely can be both.

The night air is crisp. A slice of cold butter. Instead of going to the bar, I head to the hospital. It’s within walking distance. Once there, I just stand in front of the window between me and the nursery and watch the babies exist.

I think back to the way I had to hold my brother when our parents were angry. The way he cuddled into me, almost molding to my body. If I could, I would have absorbed him to save him from the sadness I knew so well. I would have. Mom had been in and out of our lives, like men had been in and out of her. But Jared was old enough now. He could go places and I’m pretty sure he had a baby. We don’t keep in touch. We’re not that sort of family.

A mother standing next to me coughs then prays. “Our Father who Arthur Heaven…”

She trails up and looks at me. I try to manage a sensitive smile. I’m not sure how it turns out. I don’t have a mirror.

The woman says to me, “I’m a bad mom.”

“I mean you’re not a great mom, but a bad mom? You’re hardly a mom. Your baby was born, what? Three days ago. I don’t even think good moms think they’re very good.”

“Are you a mom?” she asks.

“No—” I stop myself. I should have said yes. I was my own mother—that counted for something. And somehow, I was a surrogate for Splenda—blessed be her.

She holds her robe around her frail body. “I would do it all over again just to have her.”

“Which one is she?”

As the woman points, I don’t see which baby it is because the blinds close. It’s the end of their day. Sweet dreams, Splenda.

“What’re you going to name her?” I ask the woman as we walk down the hallway.

“Bruce. After her dad,” she says.

“Bruce?” I ask.

“Yeah,” she says.

It’s a bad name, but I tell her that it’s the best I ever heard.

♦

I leave the ward and go home. I get into my cold bed. Beneath the comforter I grow colder. And I see the faces of my family, all so angry with me. I wasn’t supportive, they said. I wasn’t a friend. My mom was an addict, I tell them. She was an addict and I was too small to change anything.

I tried to remember the last happy memory of myself with my mom. We were at a park, laying on our backs. The smell of warm grass tickled my nose. My fingers pointed at the sky. It was so open, limitless. I couldn’t find the end. I was watching the clouds morph into pictures while my mother talked to some man on the phone about bodily exams. Some of the clouds were flowers, another was a Godzilla, and still another looked like a battleship. My mother slapped me across the face. Battleship was what she called a penis.

I close my eyes and will myself to sleep. It doesn’t work. I get up and open the jewelry box on my dresser. I take a twenty and two fives out. I toss a couple sleeping pills back. I grab my purse and attempt to make my way to the bar. Bingo might be over, but I know they have a wicked selection of beers.

Outside, light pollution stops the stars from showing their faces. I think about how old the light is that they’re trying to get to me. I feel a little angry that I chose to live here. Honesdale has three things to offer: poverty, old trains, and Doohickey’s bar and grill. Instead of salty nuts, Pam, Sam’s wife, makes loaves of bread. It’s to calm the drunk in all of us, she told me once. Now they were featuring late night board game tournaments. I want to see another human, more adult face.

I wander into this most familiar place.

“Now taking bets. Pots hot,” Sam hollers with his chin flapping. Sam’s a little sleazy, but he gives you beer and lets you bet hard.

“All in,” I say, sitting down on the cracked leather stool. Tonight, I would play my life savings away on Operation. Tomorrow I would find myself a new job, stop seeing those babies, go see Gary and ask him if he knew where my mother was. Take a bite of pizza, maybe. Things can change for anyone.

“I’m Will,” a man says, extending his hand.

“Are we really supposed to shake hands?” I ask, holding my arms closer to my body.

“You’re up, Ruthie,” Sam says. He tosses me the buzzer pen and winks at me. His eye disappears in the folds. My head tilts a little and I lick my lips. Preparing myself to win. Readying the bullet.

“I have never in my life played Operation,” I say.

I hold my breath and prepare to become a premature millionaire, but the buzzer goes off when I hit the edge. I lose thirty dollars. I don’t laugh. I drop the horse.

“Ruthie, baby, next time,” Will says.

“I have something for you,” I say, rummaging through my purse. I pull out the prize for my precious suitor: Elmer’s.

“Is that a glue stick?” he asks.

I nod and set it in front of him.

A woman I haven’t seen before walks through the door and demands my attention. She is taller than a medium-sized person. She is a lioness. A redheaded delight. Her lips take up her entire face. They’re red and I want to kiss them, bite them, and stick them in the pocket of my jeans.

“See what I’m saying is that you could come over—” Will bats his eyelashes onto his butter face.

“I think I’ll pass because I’m going to go over there.” I pick up the entire loaf of bread from the counter instead of cutting it into a delicate and feminine slice and sashay towards the red-head. This bread is my body. It is the last supper and our first date in the palm of my hand.

I am gliding across the floor one minute then walking through a swamp the next. My body is heavier than normal. The world is so slow. The people are tall skinny reeds whistling in the wind, moving their bodies with the beat. I never knew that Doohickey’s bar and grill had a dance floor. I can hear a dog whistle, a baby’s cry. Every footfall feels like the last Beckett in the room. I’m warm all over. I feel like a sip of tea. Before I know it, I’m standing in front of the woman.

“Hello you,” she says. Her lips are even smoother and more delicate up close, painted on with the tip of a swan’s feather. “Let’s walk.”

She surrounds my shoulder with her arm and we roam until we stop in front of one of Doohickey’s three pieces of art. It’s blue with sagging people who all seem to scream out in the same chord.

“Do you like that one?”

I nod. My eyes feel droopy like I’m not entirely able to look at the painting. I use my thumb and pointer finger to push my eyelids back. I nod again.

“Me too.”

“Can you fix me?” I ask.

“I am a doctor,” she says, touching her body up and down.

“Really? Have you ever seen a baby addicted to heroin or prescription pills? They’re cuter than normal babies because you’re all they have.”

“No, never,” she says.

The floor beneath my feet turns to quicksand. My body is falling through the floorboards into Doohickey’s basement and then through the concrete foundation into the soil, through the burial grounds and into the fossils of dragons.

“Are you happy?” I ask, waist deep in the flooring. I’m gazing at her dress and it isn’t orange as I once imagined, but more of a coral.

“I want to be,” she says. She’s now on her knees holding my chin above ground. “What do you think the world needs?”

“Less drugs, more babies,” I say.

“What’d you say? Bees?”

I frown. My head dips below the surface. I wake up in the parking lot of the hospital, leaning against a support beam. I am carried on a cloud to the nursery. I lost my name-tag, but I tell them I’m there for Splenda. We’re packing up and going home. I am adopting her. I will be a good mother, the best mother she ever asked for.

My fingers feel fuzzy. I put them in my ears to stop the music in my head. I want this to go perfectly. It will be Splenda’s newer, better birthday. When I walk through the nursery door, Bruce’s mom is there. In her arms a red baby, with blue eyes. She’s holding Splenda.

“You told me her name was Bruce,” I say, hoping my voice comes out like a growl from across the room. Like a Mama bear.

The woman blushes. “I didn’t know which one was my baby. I didn’t know I already named her.”

I want to roar at this lady. I want to go tiger and mouse on her all at once. I want her to hurt as much as Splenda does. I feel maternal without having given birth. I feel my uterus contract. I feel my claws bursting out of my fingertips.

I leave without Splenda. I leave and tell myself for the second time that I am never going back. I’d become very attached to the smallest, most delicate package.

♦

I sleep all day and night it seems. Angelica wakes me up with French toast.

“You have to eat those two slices. They were the ones from the floor.”

I stick them in my mouth whole. “I’m going to the babies. Want to come?”

“No, it makes me too sad to go there. I don’t get why you like it.”

“It feels like home,” I say. I don’t expect Angelica to understand. She lives with me because she doesn’t like her parents being religious around her. I tell her they can’t help who they are as people. She tells me that maybe I should take my own advice, handing me the house phone.

Later, I hurry to put my gown on and rip three before I make it successfully into the clothing. I open the doors to see that the cradle where my darling clementine normally is, is empty. Splenda isn’t there. My stomach falls to the bottom.

“She’s been released,” the man I’ve come to know as Ted says. “The mother came and got her.”

“She doesn’t deserve her,” I say. I cannot hide the boiling in my body. I cannot keep what I feel inside. I want to cry myself back in time and take Splenda home with me for good. Sure, I know nothing about adopting or having a child, but who really does?

“That isn’t our choice. We’re just here for them now.” Ted’s forehead creases make me think of Splenda.

“But she was mine.” I try to make myself feel big in my small clothing. I try not to let the disappointment hurt. I just want to be needed.

“You can have a new baby. We never run out of them. There’s an endless supply.”

Ted leaves me alone in the rocker in the corner of the nursery with a Carol.

After Carol was Nester and Biffy and Bud and someone who actually named their child Hancock. Eventually all the babies looked the same; the only face I could see was Splenda’s, and I hope she learned how to be happy. I hope she actually got to grow up. I hope when she looked up at the clouds with her mom, absorbed by the wild blue sky, all she could hear was the sound of my heart beating.