Content note: contains mentions of misgendering.

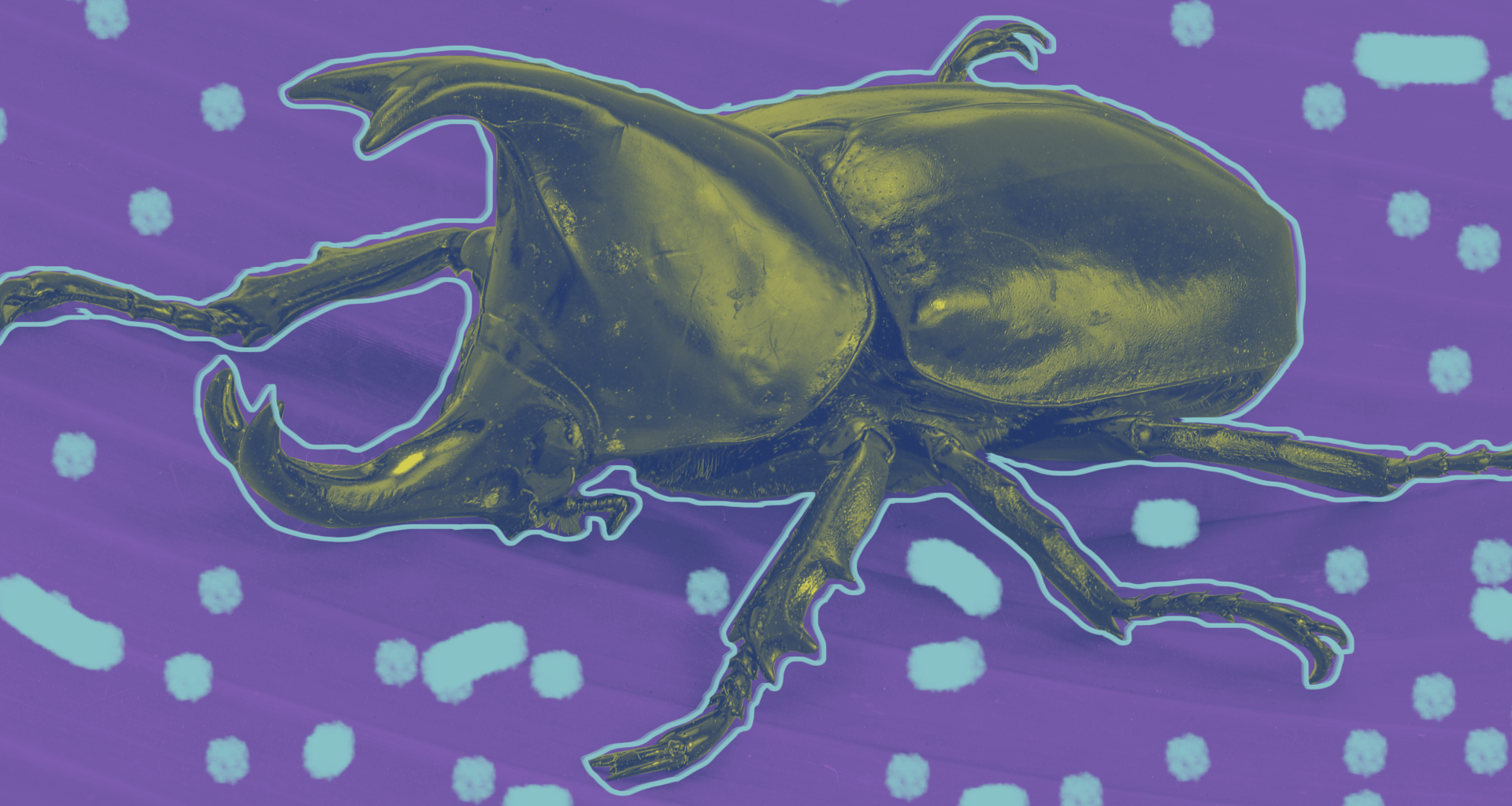

Lexa 2 is 159kg of hard chitin, sleek and black save for a pair of electric yellow elytra that glow like retroreflectors when she snaps them open. Outstretched like this, she reaches a max wingspan of eight meters, the largest D. Hercules model we’ve printed for a corporate ad show. (Think: big money, bb, and that’s it (✿◠‿◠) !!!). Tonight at 11 p.m., JST in the Tokyo Stadium, Lexa 2 as commissioned by Samsung will go head-to-head with Android’s Rhino Baby Boy™, our 15-meter Hercules against their 13-meter Rhinoceros Beetle on a super-magnified rendering of Ueno Park’s floor. It will also be my debut as a lead beetle designer, an event that will cement me as an up-and-coming figure in the industry. The bout is contractually rigged in our favor thanks to Android’s reciprocity-based agreement — a “you win one, I win one” type of deal — good advertising — all beetle matches of this scale are — but when dealing with natural organisms that have a survival drive, you can never be one-hundred-percent sure who will win.

Our beetle huffs along the dirt of the showroom floor, spreads warm breath-mist from her mandibles to fog the plexiglass of the design room. She has eyes like uncut pietersite. Lifts her horned, eight-meter jaw that could crush a Tesla like a can of fermented squid. In the wild, D. Hercules is highly sexually dimorphic: only male Hercules beetles have this distinctive horn, but Lexa 2 has no gender or reproductive organs. She’s the only one of her kind. She taps the plexiglass in front of me, requesting a snack of rotting pears. Even this close, I am never scared of her, have pressed my forehead to her cold forehead, leaned my back against her wings. She looks at me with the wisdom only an impossible being could have, the understanding of a creature who could also not exist organically in this world.

“I think she’s ready, babes,” Edie, says. They wrap their long arms around my shoulders and let go after a quick squeeze. “I like the texture you added to her leg hairs at the last minute, the fishhook barbs — it’s a nice ode to her agency as a trans creature with a purpose outside of reproduction, another way for her to say ‘no’.”

“Thanks, Edie,” I say, though on the inside my brain feels (•ิ_•ิ)?. Edie is the kind of trans person who thinks everything relates back to transness: from boba being sucked up a straw as a “phallic reverse-insemination, like the egg going into the penis’s distal meatus and impregnating your mouth” (何で??? ( ☉_☉)) to the dual gender of worms representing a healthy queering of “codependent trans futurism.” This is one of their more annoying traits, but they were also the first person to jab a T-shot up my ass at my Sailor Moon-themed “T-party,” the person I hang out most with, the only one I feel comfortable talking to about my unresolved feelings around my childhood friend, Aiko. Edie slides their lab coat off of their shoulders and hangs it on the coatrack of our plain, rubber-tiled design room, rearranges their bleach-blond, Rock Lee-Esque bowl-cut in the mirror by the door.

“Pre-party Don-ya?” they ask.

I nod, pulling my mask above my mouth and nose. As jittery as I am about the debut, there’s nothing we can do except keep tabs on the Entertainment Team as they handle Lexa 2’s transport to the stadium. “We’ll put it on the company card.”

♦

Tokyo is chilly tonight. ( ͡❛ ෴ ͡❛) Crisp, cigarette-smoke air hits the upper half of my face, sharp as the sound popping open a bag of Tongari Corn makes. November weather always incurs a strange melancholy in me, makes me nostalgic for the boyhood I never had rather than the one I feel perpetually stuck in. The feeling makes me pull for a cigarette, and I reach up to snag a candy Seven Stars from the pocket of Edie’s long houndstooth coat. As I rustle around, they tuck their hand in their other pocket and emerge with a translucent pink lighter with which they pretend to light my stick of candy. Under the skyscrapers and city lights, I curl my hand around the end of my pseudo cigarette and puff powdered sugar into the sky — puff puff puff. Edie sucks on a real cigarette and blows their smoke away from my face. This is one of the things I really like about Edie, that they’re considerate about everyone’s bodies in this way. We’ve always had an acute sense of each other’s physicality ever since we sat next to each other in a Bioprinting Ethics class at Tama Arts University, where we both majored in Insect Modeling and Animation. Shoulder to shoulder in the lecture hall, we occupied our time by passing each other squares of Calpis-flavored xylitol as our professor droned on about how bioprinting was accurate to a cellular level, real flesh and bone, that we had a responsibility to honor the sensitivities of the living beings we brought into this world.

[I think we’re all brought into this world just to suffer], Edie wrote on my tablet.I drew a cartoon stag beetle giving a thumbs-up. [agree.] [lol. glad that makes two of us. would u like to get lunch with me today?]

I drew another beetle, this one with two thumbs up.

As our lunch frequency grew from weekly to daily, we bonded mostly over adoption: them by British parents from Korea while I was adopted from Hong Kong by an American couple — the yearning to know the milk-scent of our unknown bio mothers, of never knowing your actual horoscope or even your birth parents’ names. Due to a lack of parental support over my choice of school, I made ends meet by selling my poop online to a company called Fecal Friends for ¥45,000 per week, barely enough to manage rent and daily living. The company sold my “healthy, unperturbed, disease-resistant” feces in boxes to people with chronic gut conditions for Fecal Microbiota Transplants, some of which were lifesaving. According to Fecal Friends, only 0.01% of people were eligible to give donations, yet I lived in a capsule apartment during that time while Edie rented out the penthouse of a luxury apartment, using their dad’s credit card as “Korean War reparations” whenever they went on an online bag bidding frenzy or took us out to eat. According to my parents, a lack of a “handout” would make me strong, while in reality, it made me feel small and unloved and chronically anxious about money, while Edie felt unlimited and confident and free.

♦

A text from the Entertainment Team buzzes my flip phone right as Edie and I enter the restaurant. Heading over, should have Lexa 2 to the stadium by 7 pm.

Great, I reply. My coworkers make fun of my lack of media presence, but I like having a simple phone. It keeps me grounded in the real of my existence instead of ever-encroaching virtual life.

There’s no line at Don-ya, as usual. Sometimes, I worry about the store’s owners, if it’s some old couple that runs it, if they worry about their lack of customers or if Don-ya will shut down.

“I think,” I remember Edie once saying, “that if worst comes to worst, a pair of generous investors could pull the business back up, don’t you?” And I remember that made me feel a bit better, the notion that we did have some agency in this world, enough, at least, to protect our favorite things, to control outcomes not relating to human coming or going, that we could preserve some semblance of comfort that way forever and always or at least for a very, very long time.

Edie buys a gyu-don ticket from the ticket dispenser while I choose an oyakodon ticket for myself. This ticket system maximizes both privacy and mystery — the purchase in front corresponds to an order slip which prints in the back kitchen, the finished product which a server slides under a low partition between kitchen and dining area. Neither party sees any identifying details except each other’s hands. This time, ten shrimp-patterned nails hand me my rice bowl. Above the pickup counter, I notice a poster with penguins and whales on it advertising this season’s immersive subway experience: Endless Blue. I’ve been avoiding thinking about it — Aiko’s first and last subway show as a lead designer — how she’s leaving her job to give birth, to raise a child. Just the idea of this change makes me feel far from her, as if the rubber band of our friendship and life timeline has grown so distant from its other side that it’s finally snapped.

“How are you feeling about…all of this?” Edie asks, their sensitive gaze moving from me to the poster as we head over to a frontmost table to sit.

“Fine,” I reply. “I don’t know. Bad.”

We sit down and Edie snags the pink pile of pickled ginger from the top of my bowl, folds their napkin into a tiny Peter Pan hat and places it on my head in exchange. I hate ginger. Edie loves it. Our friendship diet is compatible. Sans origami hat habit, everyone wins.

“I guess this could kind of be a good thing, you know?” Edie says, chewing delicately on a slice of cooked onion. “Like, the loss of this subway thing could help you move past her. Help you stop thinking about what she and Hiro are doing all the time. Help you let go.”

I break the mass of egg and dashi-soaked chicken above my rice like oyakodon Pangaea, let the trapped steam rise to my lips. Everything Edie is saying is right, but this is a thought pattern that’s been going on for as long as I can remember, though Aiko’s face is already losing clarity in my mind.

What I remember: a loose scattering of freckles across her broad nose, similar to the ones that speckle the twin gannets of her shoulders. Dark and complicated eyes. An analytical mouth that seems always semi-parted, as if solving an eternal Rubik’s cube, that clashes with the easy jockishness of the rest of her face. Her goalie’s body and sporty clothing-sense, long and muscled and confident, how easily it fit around the mollusk shell of mine.

After soccer practice, from middle school to high school in my girlhood, Aiko and I would walk to the Museum of the Human Body to study. The museum was full of mothers with running children. Geometric foam floors. Gigantic models of human body parts to escape in — the underside of a toenail, wound, womb. Aiko’s favorite spot to study was in the lower crook of a model ear. Nearly every weekday, we’d set our backpacks on the ground and lean against the ear’s soft silicone, our feet touching or our bodies snuggled like baby birds in the nests of each other’s arms. We wouldn’t say much, instead scratching through programming problems on our tablets or listening to surf rock through a pair of shared headphones, linked to each other as if by an electronic umbilical cord. I would often fall asleep here on Aiko’s shoulder — against her flat, even chest, catching up on the rest I couldn’t seem to get alone in my bed. Sometimes, when our lips touched or she looked tenderly at me, I felt so close it was almost like I was inside her, under her skin. I constantly wondered why she wanted to spend time with me. You have a good heart, she would say, when I asked her. I know I don’t like girls the way you do, but if I ever date someone, I’d want to be with someone like you, someone who looks at everything with love. Her words on the topic made me feel simultaneously warm and soft and wrong and horrible. Still, at the museum’s close at the end of the day, I wanted to become so small I could nestle my whole existence in the crook of her shoulder, inhale the scent of her Dove anti-dandruff shampoo until the day I grew ancient and died. I wanted to follow her forever, to see myself as she did, to become almost an extension of her like a tumor, but then she went to TUA and met Hiro while I went to Tama, and we stopped touching each other with tenderness like that, and I’ve felt ever since as if I’m missing an essential organ, as if I’ve been running and no matter how hard I breathe, I can’t quite catch my breath.

♦

I went to a German energy healer once in Shibuya that Edie’s then-partner had recommended as a last resort for the phantom period cramps other health experts said I’d have to “just deal with” post-testosterone. “Fuck it,” I thought, and made an appointment. At the energy healer’s, I lay down on a plastic folding table with a couple of bird-piss-scented pillows on top of it while the healer ran his appropriatively braceleted arms above my body to look for curse tags and chakra blockages, shivering oddly every time his hands passed my navel.

“Your solar plexus chakra is very blocked,” he said seriously, after about half an hour of arm-waving, “but that’s not your problem. The issue is here.” He pointed to my belly button and then waved his hand upward.

“A terminal ulcer?”

“No,” he said. His mullet flapped under his bald spot as he paced around the eight-foot length of the peeling room. “They’re not your cramps. They’re someone else’s. There’s an energy cord here connecting you deeply to someone — a dark color, a very deep red. To be honest, I’ve never seen one this aggressive before.”

“How do I get rid of it?”

He looked at me, his deep-set eyes owl-like and unblinking. “It depends whether you want to — whatever this cord is both gives and takes. Whoever you’re connected to hasn’t cut it either. There is something painful and unresolved here on both ends.” He took a vial of hinoki essence and held it under my nose. “Smell this and visualize the scent of the person on the other end.”

I closed my eyes and caught a whiff of Aiko’s Dove anti-dandruff shampoo. For a second, the idea that my absence hurt her too filled me with a bestial joy, then faded to pain at the idea of her pain.

“All you have to do is visualize cutting the cord, then you can begin to move on if you want to.”

“I have to shart,” I said, bolting up suddenly. I ran out of the room and down five flights of stairs, then tried not to think of the energy healer or the fucked-up cord ever again.

♦

The last time I talked to Aiko, we argued about gender, art, and ethics — how she was making “real” art while I wasn’t, that I didn’t need to do shit like this to “be a man.”

“I don’t care about your gender stuff even if I can’t understand it, Thomas,” I remember her saying, “but bringing living beings that aren’t supposed to exist without their consent into this shitty world is fucked up. And also, I think art has to actually mean something. What are these beetles — these violent fighting spectacles — supposed to mean?”

“I think they’re nice,” I replied. “I guess I relate to them. I think they make me feel real.”

Aiko sighed over the phone. “I think our lives might just not be compatible anymore,” she said.

“I’m sorry.”

Since then, we haven’t talked, and if I could, I’m not sure I’d like to talk to Aiko as the people we are now.

♦

Edie’s phone rings. A video call request from the Entertainment Team. “Hello?”

“Hello, sir, um, ma’am. Sir. There’s been an, erm, slight accident with the beetle,” says a frizzy-haired intern.

I snatch the phone out of Edie’s hand.

“What happened?” ヽ(゚Д゚)ノ

The intern pales and flips the phone camera around. Lexa 2 is lying in the lab hallway on her back, her left middle leg hanging at a bad angle. Four men in light blue Entertainment Team polo shirts with electric rods in their hands bicker among themselves behind her. Obviously, they tried to move her with force, the only thing I literally instructed them not to do.

“You had one fucking job,” I say. “Did you even read my instruction pamphlet?”

“I’m terribly sorry, sir — ”

“You should be. I’m coming over.” I hang up then hand the phone back to Edie, who pulls their coat on and walks with me to the door.

“We have time. We can fix this,” they say. We walk swiftly through the darkening streets, elbowing our way through schools of schoolgirls and salarymen as we make our way back to the lab.

When we get to the office, the Entertainment team is still standing around uselessly.

“Hello, sir.” The intern from before rushes towards me with a clipboard in his hands, his glasses askew on his face.

I ignore him and move to the lab hallway to check on Lexa 2, who is huffing unhappily and rolling back and forth on her back on the lab floor. I run my hand over her left wing until she stills and pat her head gently.

“What did they do to you?” I ask. I examine her bent leg — definitely broken. Fucking Entertainment Team. I rub Lexa 2’s wing again then head to the printing room to print out another leg just as oil-slick iridescent as the first. It takes about thirty minutes to complete. Once it’s done, I grab the leg, my laser, and my hand-held grafting machine from near the printer.

“I’m coming, Lexa 2,” I say.

Edie hangs back when I return, knowing my work style well enough not to say anything while I kneel next to Lexa 2 and take out my laser.

“This might hurt a bit,” I say.

Lexa 2 huffs.

“I know. I’ll count to three.” I rub her head as I count down, then pull gently on her injured leg before lasering it off where it meets her torso. Lexa 2 starts rocking back and forth and makes a pained hissing sound. It’s best to finish tender things quickly, so I grab the leg and the grafter and fix the new leg where the old one used to be. The tool emits a pulsing green light as I run it around the leg’s base, attaching shell to shell, nerve to nerve. When I’m done, I hold the leg for six minutes to let it set.

“All done,” I tell Lexa 2. She twitches her leg. Around the leg’s base is a little line where the new leg begins, evidence of the graft that’ll drive me crazy.

“I’ll handle the Entertainment Team,” Edie says from the other side of the room. This time, the team lures Lexa 2 the right way to the truck with a bucket of rotting pears, clips her into her harness, and hits the road.

“I’m sorry again,” says the frazzled intern.

I swallow and turn away. ಠ╭╮ಠ “Yeah, I’d be sorry too.”

♦

Edie’s family’s driver, Musa-san, picks us up at the office in a blue Aston Martin DBX after the incident.

“Hello, Mister Edward. Mister Thomas,” Musa-san greets. He pops open the side door and we climb in, Edie before me, their demeanor immediately sharper and more masculine, makeup rubbed with a wet towel from their face.

“Good evening, Musa-san,” Edie says. It’s always unsettling to see them like this: in their “London Poster Boy drag,” the one they use with their family and company executives above us.

“Why pretend?” I once asked them.

“It’s easier this way,” they replied.

To me, they are always Edie regardless, but sometimes, it feels like a lot for them to hold.

“The jacket on the left is yours,” Edie tells me authoritatively. I unzip the suit bag they’ve pointed to, finding my plain, navy Tom Ford jacket and matching pants freshly dry-cleaned over my starched white shirt. It’s become a hectic tradition for us to change together in the car, so Edie takes their pants off and pulls a pair of tailored grey trousers over their legs, a flash of affirming hairlessness underneath. Fashion-wise, they’ve always been the sharper of the two of us, cuts of cloth fitting them perfectly while I tend to size a little larger than myself. They’re tall, stork-limbed. I’m more bashful about my newly stocky boy body. Watching them, I jitter my leg and tuck my hair repeatedly behind my ear. They rub pomade in the palms of their hands and slick their bowl-cut back.

“Behold: my Dunkirk pompadour,” they say.

“You look nice,” I reply. What I want to say: you still look like Edie to me.

♦

We peel off at the Ritz-Carlton by Tokyo Stadium and take the elevator up to the rooftop bar. Samsung execs prowl the area, mostly middle-aged Japanese men with highball glasses in hand. The whole affair wracks my body with nerves.

“On your right,” Edie whispers, raising their chin towards a stout, sweater-suit-clad guy with a skunk-like combover.

“Yikes. Must be a bad everything day.”

“No, on his left wrist. That’s a Patek Philippe Nautilus. Like, $500k. Daddy.” They swipe their tongue against their teeth.

“Ew.”

Edie nudges me, then slips back into their Poster Boy persona. “Drink it in. It’s your night. Let’s see if the bar has Ramune.”

The bar does have Ramune. I grab a lychee-flavored one while Edie sticks to an old fashioned with five shakes of bitters, then follow them towards the leftmost corner of the rooftop where the other young folks are gathered. There’s Imani and Aki from Marketing, Tomomi and Betelgeuse from Finance, Betelgeuse’s partner, Chieko, that weird, watery-eyed Made Woman, Ellie, and several other colleagues taking selfies in front of a living succulent wall.

“Big debut, huh, little guy?” Aki says, ruffling my hair. I begin to feel bad, bad, bad.

“Not so big yourself,” Edie jokes, looking down towards Aki with a mix of charm and condescension only a prodigal scion like them could pull off. Aki laughs awkwardly, then excuses himself to look for a friend. Edie squeezes my shoulder. I stiffen. I want to tell them I didn’t want them to stand up for me, that I could’ve handled the situation myself, but I lack the fire to say so and smile instead. (ง’-‘︠)ง This is what I hate about myself: my smallness, my inability to speak my thoughts or show what’s in my heart to anyone, that I loathe what everyone claims to like most about me — my softness and sweetness, my hesitance and people-pleasing that everyone mistakes as “love.”

“I think I’m going to go for a walk,” I say. I don’t wait for a response, instead cross my arms around myself and head towards the subway station, towards Aiko’s Endless Blue. The scared and animal part inside of me feels like Lexa 2 on her back with a broken leg, wants to be nestled in Aiko’s arms, whole and in good health and sure of who I want to be with, less sad and pathetic and goddamn alone. (╥_╥) (╥_╥) (╥_╥) I touch my Suica to the turnstile at the station entrance that leads to the show route, jog down the stairs to catch the train right before the doors slide closed. Inside, I find a seat next to a bopping hologram of a macaroni penguin. HELLO WORLD, a prerecorded clip of Aiko’s sly, low-pitched voice says, and the train begins speeding forward, past the station and into the world of Endless Blue.

♦

The first thirty minutes of the train experience begin above the ocean, holograms of sea waves at the train’s bottom and gulls and blue sky above it. It is as if the train is floating above water, sun fractalizing on a clear surface, the macaroni penguin next to me teetering as if rocked by waves. Outside the train’s window, jellyfish begin to float crystalline on the water’s surface, the occasional dolphin splashing suddenly up from underneath. Some sort of spray hits the inner cabin and it begins to smell like salt and crab shells all around. Around 70% of the earth’s surface is covered by the ocean, Aiko’s recording says. Her voice feels close enough to make my neck hairs stand on end. The sound of her makes me recall the nights I couldn’t sleep unless I listened to her 3D modeling lectures on YouTube, how they helped me regulate my breathing, how I reached for her hand that wasn’t there in the dark. In the videos, Aiko was still athletic but wirier and with an asymmetrical haircut that hit above her shoulders now, a sleeve of scientifically-drawn tide pool creatures covering her left arm. Yet, we have explored so little of it, the train recording continues. I often wonder what’s under the surface of things, what kind of lives we’ve never seen. What is it like to live a day in the life of a squid? A horseshoe crab? To be as large as a blue whale or as tiny as a single krill? These are the questions I ask myself daily, how the mysteries of ocean life could inform what it means to be a mother, a better wife, a better friend.

The train seems to tilt downwards below the water’s surface, descending until it reaches a colorful, clown-fish-populated reef. Spotted garden eels pop out of the ground and sway alongside outgrowths of kelp. My penguin neighbor presses its face against the window, its yellow crest flopping curiously at the sight. I look for and admire the smaller details — the texture of scales, the shading behind a blue dory’s gills. I think of how each pixel was carefully drawn by someone, each animation proofed thousands of times before the final result. How much grit it takes to render something on this scale, how thankless this work is, how little people know of the time and sweat that goes into sequential art. Coral reefs are living animals that work together to clean the ocean and provide homes for 25% of marine life. These reefs can date back to as far as 240 million years ago, existing symbiotically all that time. From the reefs, I learn that being alive can take different forms for everyone. From the heterocongers, I learn that changing how one presents themself to the world based on other people or the day is okay. As I grow braver each day, I know I would like to try a bolder look too.

A blue whale passes outside and takes up the entirety of my window, its barnacled body rendered beautifully in 3D. The outside of the train is dark as the whale slaps its tail one last time against the ocean, the train caught between the walls of a gaping trench. In the deep ocean arena, a macropinna microstoma wiggles by, its weird, transparent head with all organs visible unsettling to the eye. Between the trench’s rocky walls, underwater volcanoes light the dark with mid-sized red bubbles. The train continues through the trench until it suddenly stops, suspended in a dark emptiness. The water stirs every now and then but otherwise, it is silent. As the temperature inside the train grows colder, I feel lost, putrid, and terribly alone. In truth, motherhood scares me, Aiko’s voice says, quietly. I am terrified to enter this next chapter of my life. When I can’t sleep, I wonder what qualifies me for motherhood even though I know it’s something I want, yet I still feel unprepared, like a little girl sometimes. I am so scared of the world and all its changes — culture, climate, technology — but I am also excited to see what this new chapter brings. Which is to say, I know the unknown can feel scary, but it is also full of the queerest light. In the middle of the train cabin, an anglerfish weaves spherically between the seats, luminescent fin ray bobbing up and down. The train begins to move forward again and slowly rises past the coral reef where a series of squid pass by, following us all the way back up to the surface. Thank you for joining me, Aiko says. I’m sorry to be leaving you so soon. Whatever adventure you go on next, I hope the hands that hold you will be kind. My penguin friend flaps his wings once more before disappearing, and I am left alone in the train station again as the doors open. I sit on a cold bench and wrap my arms around myself as I process the subway ride. At the end of the day, I think Aiko and I are different people with a common core. Maybe we all are. I think I want Aiko and her baby to be happy. I think I want to be happy too.

I exit the station at 10:30 p.m., taking the light rail to Tokyo Stadium.

“You made it,” Edie says.

I give them a quick hug and a high five. ヽ( ⌒o⌒)人(⌒-⌒ )ノ “Thanks for being my friend. You are my favorite Edie out of all the Edies I know.”

Edie looks back to say something but is cut off by a series of small fireworks, white and red in the sky, tails trailing gold. In the stands, spectators roar as our giant beetles trot into the center of the stadium, our fans fascinated at what our teams spent hundreds of hours to make. Lexa 2 looks shiny and powerful, ᕙ(`▿´)ᕗ her leg-seam invisible from this vantage point. As I stand with Edie, I feel strangely open to it all. In my small life, for a second, I imagine the red thread between me and Aiko loosening just as Lexa 2 raises her impossible horn to the sky.