If the English Sir Isaac Newton, like the Chinese Empress Leizu, had been hit on the head by a silkworm cocoon instead of an apple, and had unraveled the mile-long thread until he came upon the worm, maybe he would never have realized that f = ma, maybe scientific specialization and determination and molecularization would not rule knowledge and pass as wisdom. Perhaps, if Newton’s brain had brought to bear upon the silkworm, the world would be ruled by beauty?— and perhaps scientific truths can be spun out by story. You are familiar with Newton’s three laws? Force acting on another force. Causing motion. To wit—

My sleek silver car screams through the desert, chasing the sun’s short arc from west to east. The stowaway hummingbird in my car speeds through time even faster than it usually does: it beats out its life in about five years. I press my foot into the car’s metal, its pistons shuddering with white heat. I know my mother will complete the silk robe today, which she has been sewing for my twenty-seventh birthday, for five years, since I left home.

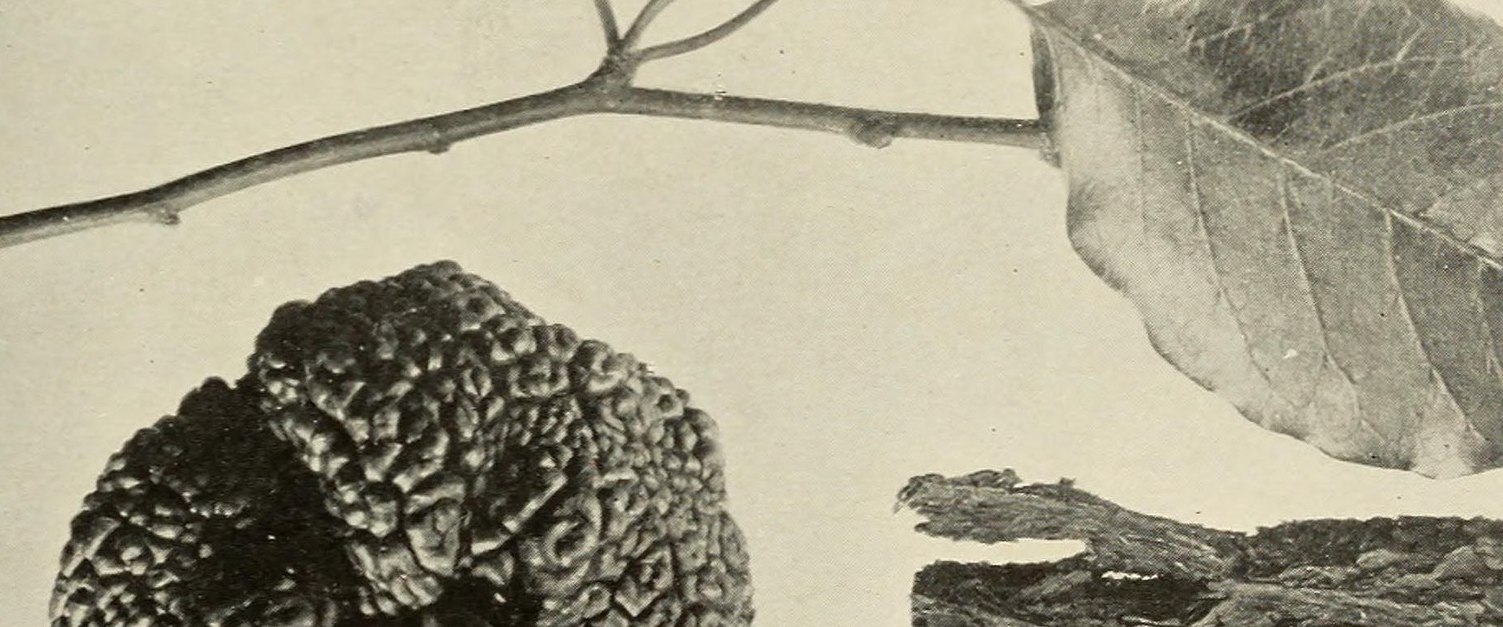

Beauty, what the silkworm gives us, is all we care about in the east of the continent and it’s spoiled us. We don’t know what slings the planets in their orbits around the sun, don’t know that the daylight we receive is old and very tired, but we know now that we can never intervene in animals’ lives, we can never take them away from themselves. We spent all our time crossing and mating silkworms and they lost their ability, or their wills, to reproduce. We planted all mulberry trees; we felled the forests. Now we realize. We’ve spent decades trying to undo our ecological handiwork, our scaling up, but at least we have the silk everything: silk blouse, silk pants, silk gloves, silk scarf, the prized silk slip cut on the bias.

The black and white speckled hummingbird is now resting on the silk-lined car seat, ignoring the flat plains as they fly by, its eyes open and tiny chest vibrating. Soon we’ll be in the shaded woods.

I am worried that the hummingbird will die today. But I realize I love my mother. I want to show her the hummingbird, I tell her over the phone, which she can’t ever have seen, the species which has been my companion since I parked my car five years ago outside the garden, an oasis surrounded by dust, and found my place there, which was: quietly sitting and reading and thinking, quietly harvesting green shoots and cutting them into a pan. The people there, solemn and exact, they told me, every harmful thing we do will come back to us.

The sun is mysterious as ever, blazing today, and I look up sometimes, and I look up at nights at the moon and stars too, but in the east, I looked more at the ground, at the droppings of the silkworms and their shells, their carcasses. On the other side of the continent, all kinds of trees, black locusts and manzanita and redwood, and another ocean hemming us in. Now I know our limit.

When I see my mother, when I go back, I’ll have proven how large my guilt has grown, for leaving my mother with the silkworms. We used to be there alone always, for beauty: placing the larvae on mulberry, leading them to their partners, boiling the pupae for their treasure, then eating them. This absolution is pulling me, my car, faster than I could imagine. I look to the hummingbird, which has begun bobbing up and down on invisible wings in its eleventh hour.

The car collapses, completely spent, at our sprawling home, the roof scalloped and crenulated with thousands of tiles. I think I’ve beat time. The sun’s red disc just beginning to slip below the horizon. I rush inside with the hummingbird, not dead. There is my mother in the darkness of the sitting room, enveloped in silk curtains, slumped in her carved chair. I rush to her side. Her face is still. Beside her, the robe she has been sewing for me. A jade and cerise hummingbird stitched on the cool gauzy fabric, tongue in hibiscus. The work of thousands of silkworms. Has she just collapsed, the scant dust she allows to stay in her house just settling? Why didn’t I come yesterday? What makes one thing do another? What is action, and reaction; sacrifice? Her hands just warm. The hummingbird leaves me, out the door.