FEATURE ESSAY // By Robin Hendricks

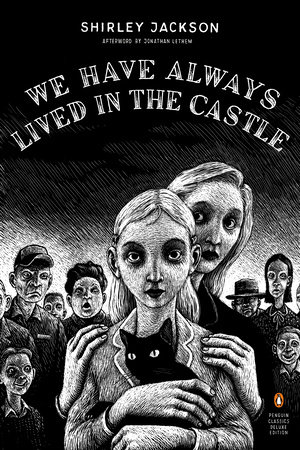

A Relief and a Horror

Reading Shirley Jackson in the Time of COVID-19

The first chapter of Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle, where Mary Katherine Blackwood makes her last ever trek to the village, is a study in avoidance. Merricat pictures the village as if it were a game board, losing turns when it comes time to walk across Main Street. The villagers watch her, speak to her and about her in veiled jeers, but they don’t touch her or get close enough for her to touch them. And when one does—Jim Donell, the most singularly antagonistic of the villagers—Merricat dissociates, retreating in her mind the way she cannot physically. Jim crowds her at the counter at Stella’s, sits on the stool beside her, pivots until he faces her profile. Trapped at the counter, Merricat thinks, “I am living on the moon,” her mantra of escapism throughout the novel.

This mantra becomes her ritual, and Merricat abides by her rituals. She only crosses the road when no cars are in sight; cuts the quickest path to the gate that marks the start of the vast Blackwood property; then, if there weren’t too many run-ins with villagers, she buries “an offering of jewelry out of gratitude.” This, she thinks, will keep her and her sister, Constance, and her Uncle Julian safe.

Jackson presents Merricat’s trip to the village as an odd and chilling errand meant to raise the hairs on the backs of our necks, to pique our interest. But now, as the threat of COVID-19 hangs over our doorsteps, the effect has shifted. What’s meant to seem absurd—the constant awareness of everyone in the room, the claustrophobic atmosphere in Stella’s, the intense relief when the gate shuts at the end of the errand—is suddenly our new normal.

When we leave the house, we abide by our rituals. We put on our masks, pack hand-sanitizer, disinfect the shopping cart, make note of where people stand and if we can see their noses or their mouths. We stay six feet away, stand behind plexi-glass at the cash register, cringe as we key in the PIN and touch buttons others have touched. At home, we wash our hands up to our elbows in scalding water and anti-bacterial soap, clean our phone screens with Clorox wipes. If we’re good, we wash our clothes in hot water and take a shower. As we step out, we hope that we are safe, that the rituals have worked.

We’re better equipped now than perhaps ever before to empathize with and examine how Jackson conveys the Blackwoods’ sense of isolation, both social and physical, from their community. And in doing so, we may be able to gain further insight into what Jackson—who was no stranger to isolation—has to say on the subject.

♦

The Blackwood house sits far back from the village and highway on land that’s grown wild from disuse. A fence runs along the border, placed there by Constance and Merricat’s father at their mother’s request so the “common people,” as she called them, wouldn’t walk through the property anymore on their way to the bus stop. Merricat internalizes her mother’s elitism, associating wealth, and the lack of it, as a reflection of morality. She narrates, “It was as though the people needed the ugliness of the village, and fed on it… and the Blackwood house and even the town hall had been brought here perhaps accidentally from some lovely country where people lived with grace.”

The Blackwoods’ wealth affords their physical separation from the villagers. We see this today as affluence excuses the rich from forced proximity. They can leave epicenters and quit any job with unsafe working conditions, while essential workers often depend on these positions. And as schools reopen, the question of whether children will return often depends on the parents’ resources and ability to stay home or pay for childcare. Now that distance can determine life or death, it’s a prized commodity we’re learning only few can afford.

The sisters depend on distance. They shut themselves away from the village more than their parents ever did, and with Merricat the only one to venture off the property. In this way, they mimic the jars kept in the cellar where generations of Blackwoods left their goods. Merricat calls the jars “a poem by the Blackwood women.” The sisters seal themselves away in their house and on their land, as Constance seals the lid to a jar of apricot jam, with the hope that no outside threats will get in. But given enough time, anything will spoil.

The seal breaks when the Blackwood house burns and the villagers come through the gate to tear it apart, throwing chairs through windows and smashing precious heirlooms. Uncle Julian dies off-page, the last vestige of the older Blackwood generations. The sisters learn of his death as the villagers tear into the house, and there’s no time to mourn. All they can do is try to survive.

It feels a bit like that now—not the mourning for a passed loved one, necessarily; but shared mourning for the hundreds of thousands of lives this virus has ended. After a tragedy, the names of those who died will be read on the news; their photos will display on television screens; loved ones will give interviews. That can’t happen now as the virus spreads with too many deaths and no pause. This tragedy exceeds comprehensible scale and it isn’t yet finished. And like Merricat and Constance outside the burnt Blackwood house, we exist, numb, trying to survive until it’s done.

After the villagers disperse, the sisters are left to pick up the pieces. Or, more accurately, to sweep the pieces into the dining room and shut forever all the doors except two, living exclusively in the kitchen and Uncle Julian’s old bedroom. Merricat boards up the windows and creates barricades from debris.

They’re completely alone, and yet say they’re happy. The novel ends with the sentence, “‘Oh, Constance,’ [Merricat] said, ‘we are so happy.’” But is it possible to be happy when living like this, so separated from the outside world? This gets to the heart of how Jackson sees isolation: a state of existence that simultaneously provides freedom and takes it away.

Merricat’s mantra, “I am living on the moon,” used to be her method of dissociation from the villagers. She wanted some place far away, untouchable. In a way, she gets that after the house burns. She and Constance are physically closer to the villagers now that their land is open, but the expectations to conform are gone. The pride is gone. All the rules aside from the ones she and Constance make are gone. When Constance washes their only pair of dresses—the ones they wore when the house burnt—she wears Uncle Julian’s old suits and Merricat wears a checkered tablecloth tied with a curtain rope. The image is odd, but fitting. Constance, who for so long played the docile helper, fitting ideally into the role that society wrote for young women, is no longer at the Blackwood family’s or Uncle Julian’s beck and call. She has the freedom to cross that gendered boundary, to live as she chooses, doing what she wants when she wants. That’s one thing isolation provides, the chance to self-define. Alone, there’s no need to modify behavior to fit anyone else’s preconceived notions.

Merricat, in her tablecloth, looks like a child playing dress up. By the time the novel begins, she’s eighteen years old, and the last chapter implies they live in this way for years to come. But, as Jonathan Lethem notes in his 2006 introduction to the novel, it’s easy to forget she’s an adult. Her vast imagination and habit of disjointed conversations—always carrying on her own absurdist and unrelated half—lead us to forget her age. She mentions certain rules, like not to hold knives or “touch Uncle Julian’s things,” and while at first it seems Constance imposes these rules, we later realize she doesn’t. Sometimes Merricat invents new rules on the page, but it’s unclear if she makes them as a way of limiting herself—an obligatory penance for sprinkling arsenic in the sugar and killing her family—or if her parents made some of these rules before their deaths and she continues to enforce them out of guilt.

And yet, her childishness almost functions to absolve her of this guilt, going back to the escapism proffered in her mantra about the moon. So much of her existence revolves around imagination—wandering around the wooded property, blocking the entrance to her hiding spot with fallen branches, burying her mother’s jewelry—that she might as well be imaginary. Her habit of indulging interiority has the effect of deconstructing the real world and, by association, her crimes against her family.

♦

It’s only natural that we, like Merricat, grow intimately more familiar with our own interiority when alone. The almost desperate shared languages from the early days of social distancing, about Tiger King and sourdough starters, seem quieter now. At first, those common experiences were a relief, arbitrary but connective. Things have changed since then; the ache for community persists, but it feels like there’s a newfound pull toward the self. Many of us—not all, namely essential workers and parents of small children—now have the time and space to explore our own interests and examine who we are when left to our own devices in this indefinite waiting room.

♦

Time passes for the Blackwood sisters. Ivy hides the burned-out roof; children play in the yard, mothers picnic on the grass; Merricat and Constace sit inside their barricaded house and watch the villagers without their knowing. This is the sisters’ only contact with the outside world, other than the food the villagers regularly leave on their doorstep, often accompanied by written apologies for items they broke in the house. The final gift of the novel—eggs that Constance says she will use to cook omelets in the morning—is an apology on behalf of a child who recited the first line of the villagers’ rhyme at the front door before leaving it unfinished as he ran away in terror: “Merricat, said Constance, would you like a cup of tea?” When she brings in the eggs, Merricat says, “Poor strangers… They have so much to be afraid of.”

Merricat seems to believe the villagers provide food out of fear, perhaps for what might happen if they don’t atone for their sins. Lethem describes the food as “offerings laid at [Merricat’s] feet” to “repent of [the villagers’] cruelty.” Like the sisters are goddesses, the house a shrine. To a certain extent, Merricat may be right. A mythology of curiosity develops around the destroyed house and the sisters who live inside but never appear, a communal oddity everyone wonders about.

♦

Lethem explains in his introduction that the village Jackson depicts in We Have Always Lived in the Castle mimics her experiences in North Bennington, Vermont, and the recent biopic Shirley (2020), based on the novel by Susan Scarf Merrell, seems to agree. The film—which explores the relationship between solitude and madness and gives Shirley the memorable line, “What happens to all lost girls? They go mad”—portrays Shirley (as played by Elizabeth Moss) as a subject of fascination and vitriol in her town. Many admire her writing, can’t get enough of it, and will excuse any socially awkward behavior she displays as the cost of associating with genius. But there are others who see her as a freak because of her reclusivity. At the beginning of the film, Shirley hasn’t left the house in two months and rarely gets out of bed. We see her smoking in a white satin nightgown, staring at the ceiling, utterly still. Her narrative runs opposite the Blackwood sisters’; it tracks her reemergence back into the community. Or, if not the community, then into the role of a wife. The film ends on a longshot of Shirley and her husband dancing as the camera outside the window zooms in, right after he commends her new manuscript and calls her his “horrifically talented bride.”

Jackson, alienated from her own neighbors, writes a fascinating and nuanced depiction of the villagers in We Have Always Lived in the Castle; they seem vile, almost evil in their intent. On the night they destroy the house and trap the sisters in their circle of bodies, certainly about to commit an act of violence, they seem inhuman. But later, when they individually begin to send food and apologies, it doesn’t seem to be fear-driven like Merricat assumes. Rather, they seem remorseful, like they would take their actions back if they could. This echoes the scene in the first chapter when Merricat goes into Stella’s for coffee; Stella is pleasant until Jim Donell sits down at the counter and then she struggles to contain her laughter as he bullies Merricat. Jackson demonstrates the villagers’ capacity for compassion alongside their capacity for hate in order to critique mob mentality and the concept of Us versus Them.

♦

A survivalist mindset pervades every day of isolation. If anyone could have the virus, then we need to behave as if everyone does. And that thought process is damaging, to say the least. When every stranger is a potential threat, every errand outside our homes feels like Merricat’s final trip to the village. The presence of masks connotes a shared understanding: both parties are afraid and will keep their distance, like a friendlier version of Merricat’s encounter with the women in the grocery. But then there are people who refuse to wear masks; like Jim Donell, they wield their refusal of fear like a weapon. It’s a line drawn, concrete and definite, in the sand, one that feels like it will last far longer than the virus. When we’re near them, we’re Merricat, trapped against the counter, claustrophobic and fearful and homesick.

The pitying way Merricat says, “[The villagers] have so much to be afraid of,” indicates she feels she has nothing to fear. Merricat and Constance are so afraid that they shut themselves away, changing their lives completely so they would never have to face their fears again. Because they’ve made these changes, which are shockingly and tenuously sustainable, they have deluded themselves into believing they live without fear.

The word castle evokes a fortress, aristocracy, imagination, but the whimsical Merricat only calls the Blackwood house a castle once. After the fire burns the roof away, she narrates, “Our house was a castle, turreted and open to the sky.” That description of a broken castle admits the sisters’ vulnerability. This house, their protector for so many years, is destroyed. She can see the sky just by looking up. Jackson uses the title to drive home the truth of this novel, even if it’s a truth Merricat will never understand: the Blackwoods have always lived in the castle and have always been vulnerable. Like with the jars in the cellar, there is no perfect way to seal their lives shut to the outside world. There is no moon to live on, no untouchable place, no untouchable way of living.

♦

That thought is a relief and a horror in the time of COVID. We never asked to live in solitude, our communities essentially cut down to our households, communication limited to pixelated video calls with lagging sound. It’s a guilt-ridden thrill to think our isolation is imperfect, that our lives as we knew them are not gone but leaking in through the cracked-open lid of a jar, the burnt roof of a house; that perhaps we can use this time to find some version of the freedom Constance and Merricat enjoy in the final chapter, when we are separate enough to learn who we are in the absence of societal roles while still remaining connected to reality. At the same time, Jackson’s message of constant vulnerability is a sickening reminder that no rituals can offer perfect protection from the virus. Nothing can. In a world so like Jackson’s fictional village, where everyone poses a threat to ourselves and our families, how can we ever feel safe?