Review // by Lucia Senesi

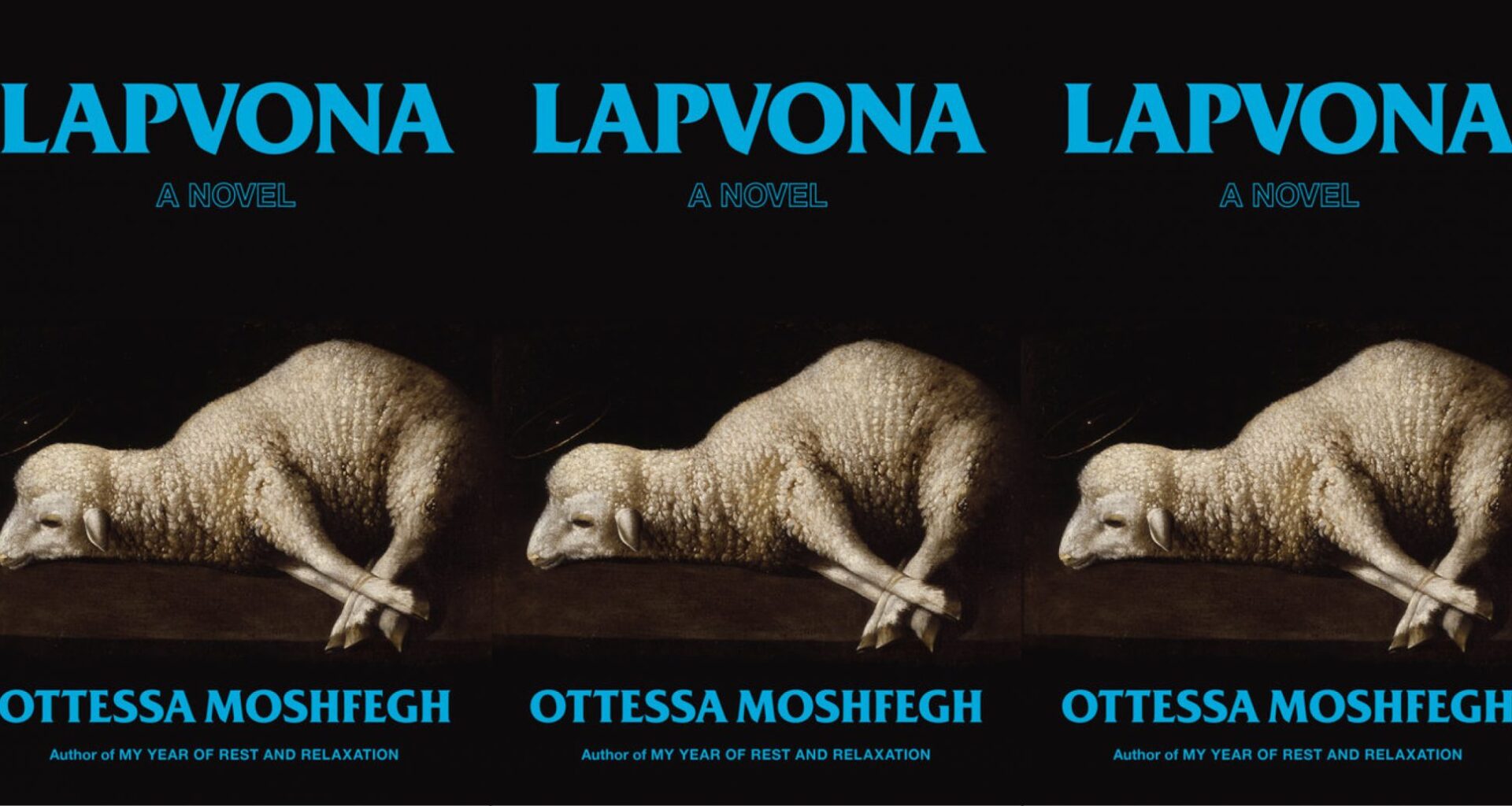

Ottessa Moshfegh’s latest novel, Lapvona, is an allegorical tale of power dynamics and contradictory feelings, a quest for faith and a need for sin. Its search for imperfection and vulnerability is very human, even tender. It’s also typical Moshfegh: superbly stylish, acutely funny, highly entertaining and extremely original.

Of course, it is well known that these things can be problematic in a regular writer: style becomes tiresome when it lacks meaning and sarcasm is hard to balance, as much as entertainment bores the intelligent reader and originality reveals itself to be the oldest thing in the world. But Moshfegh is not a regular writer and somehow manages to handle all these tools perfectly.

From the sublime to the ridiculous, people say in Europe, it is only one step. Moshfegh has mastered the art of setting herself on the border of the sublime, always. She knows how to push the reader and how to reward them; she mistreats the reader only to rejoin and cuddle them, and then push them back again to a cruel, sometimes dark magical realism in which you keep wondering if she will ever come back to rescue you. (Spoiler: she always does.) The world is an awful place, Moshfegh suggests, but if we stop lying to ourselves and to others then there’s a chance that we’ll see it become tolerable, if not gracious. There’s grace in the grotesque, seems to be the project at work here, and this means that, yes, even shit can be poetical when it’s your primary condition. “Studied grace is not grace,” Moshfegh wrote in My Year of Rest and Relaxation, “charm is not a hairstyle. You either have it or you don’t. The more you try to be fashionable, the tackier you’ll look.”

Nobody tries to be fashionable in Lapvona. Not the ugly, fragile and malformed teenager Marek, nor his father Jude, “whose bones and muscles were like polished bluffs beaten by an ocean, soft and luminous despite his skin being grimy and often covered in lamb shit.” In the same way, Agata can’t be fashionable, since she’s too busy trying to survive confinement and sexual abuse, while Lispeth must work as a servant for people who don’t have one quarter of her intelligence, faith or self-denial. And certainly the 100-year-old wet nurse, Ina, has no time for fashion, having to learn how to use her new horse eyes and maybe look for a young husband. As for the rich, they were dull and they were repetitious, Hemingway would say, and in Lapvona, this is true whether they drink too much or not, play too much or not; dressing up isn’t their first preoccupation. Lapvona is a choral book, although the storytelling mainly follows Marek, a kid who grew up dreaming of the mother he’s never met and ignoring the fact he’s the product of a rape-story more than a love one. This need for affection sets the drama, as Marek tries to connect with the other characters in the worst possible way: expecting to find in these relationships what his mother deprived him of. Jude demonstrates his affection by beating him, and the wet nurse, who still breastfeeds him, can’t keep him away from tragedy, not even with her magical powers. Marek’s coming of age is defined by death, and death is what brings him to his (material) fortune, as he will be adopted by the rich lord of the village, Villiam. Eventually his mother, Agata, will reappear; but this trick of fate only aggravates the drama: Marek is the child of an incest and Agata genuinely can’t stand him: “Everything he asked her was a plea for affection. He didn’t care for her, not really. He only wanted to seduce her by seeming to care, so that she would care for him. Children are selfish, she thought. They rob you of life. They thrive as you toil and whiter, and then they bury you, their tears never once falling out of regret for what they’ve stolen.” Agata, who again finds herself pregnant after being raped, is welcomed as a new Madonna, an event that allows her to keep her distance from Marek and Jude, from “their stubbornness and their neediness, their longing like a rope around her neck.”

Moshfegh goes back in time, as she did in her first novella, McGlue. There the protagonist was interrogating himself: “My mother says I am the son of the devil. How could she be wrong?” But the real protagonist of Lapvona seems to be Lapvona: a fictional medieval village, hypothetically set in the Middle East and stormed by bandits. The village is the place that prepares a destiny for its characters; its harshness, its brutality, its inequality are so much a part of the inhabitants’ temperaments and bodies that they are as natural as the air they breathe or the lamb shit they walk through. There’s dirt in Lapvona, but there are also blue skies, sunshine, green trees, winds and flowers and rocks and birds, birds that might be angels. “Why is it, Waldemar,” Moshfegh wrote in her short story, A Better Place, “that when something here is so beautiful, I just want to die?”

Lapvona is an allegory and this means that violence and madness work as archetypes: if you’re not disgusted, you’re not paying attention. The narrative plays with the dimension of myth, although mutilation, murder, suicide, cannibalism and fratricide don’t really happen out of pride or revenge; sometimes they’re acts of no meaning, ways for personal regeneration, desperate forms of escape, or perhaps attempts at mercy. The reader who is looking for salvation, anyhow, better not hope for it in nature or faith, as Moshfegh has no intention of romanticizing any of that. In her novel, faith is a double-faced instrument and God, for all she cares, could be alive or dead; in any case, nothing is coming down to do the work for the characters. As for nature, it’s there with all its beauty and danger: it’s the element of pure living and the one that brings death, often in an abrupt, unexpected way. It makes complete sense, anyway, because in Moshfegh life and death are just two movements of a bigger symphony and nothing to get too worked up about; just nature taking its course. This pervasive cruelty is not just aesthetic: it is at the service of the reader as an ultimate call for total honesty between them: author and reader. It’s like hearing again an old voice that we know, one coming from her first novel: “But tell me, Miss Eileen, have you ever wanted to be truly bad, do something you knew was wrong?” The peculiar relationship with the reader who’s being asked to participate in the drama instead of just passively suffer it, is what Moshfegh has always taken care to accomplish, although it is in Lapvona that this aspect assumes a deeper tone. In her previous works, the reader was at least sure of the presence of an omniscient divinity—the author—who was the only entity they had to rely on; whereas here, Moshfegh suggests that if there’s such a thing like a God, she has nothing to do with it. It’s true it is not her first concern to prove the existence of God, but it is her concern to underline that we, as humans, are not that important, nor that pure, exemplary or entitled to a destiny. “It is not man/Made courage, or made order, or made grace,” wrote Ezra Pound, “Pull down thy vanity/I say pull down. Master thyself, then others shall thee beare.”

In her old house, Moshfegh had a note on the window. It said: “Vanity IS the enemy.” It’s also a recurrent theme she likes to explore. In her short story, Bettering Myself, she wrote: “Makeup made a girl look so desperate. People were so dishonest with their clothes and personality.” And in Eileen: “Getting dolled up was completely silly, of course. You can always tell something when a woman is overdressed: either she’s an outsider, or she’s insane.” In An Honest Woman, she went on: “‘She’s a plain Jane’ is what he told his nephew when he came over for breakfast. ‘No substance, no depth. Full of herself for no good reason.’” And in Death in Her Hands: “You think your life is so hard because you aren’t some whore on the television? Ugly girls find honest husbands. Thank God you aren’t a beauty.” It is not hard to understand why this kind of writing either irritates or pleases readers; anyhow Moshfegh’s critique of vanity seems to have roots more in politics than— as in the case of Pound— in Catholicism. Through all of the patriarchy’s artful variation across time, vanity has remained the primary and indispensable tool with which men control women, and thus the world. This is especially true for the society of the image (a darker evolution of the Society of the Spectacle) that Moshfegh likes turning into satire: a place populated by self-obsessed humans who believe that the representation of reality is in itself reality. In 2018, I interviewed Moshfegh on My Year of Rest and Relaxation and asked her about the protagonist’s choice to give away her expensive clothes to step into her real self. “Okay,” Moshfegh told me, “so she gave all her shit away and now she’s wearing secondhand clothes, stuff from the 99 cent store. It’s a little bit delusional to think that just doing that, you know… only a rich person would see that as freedom.”

The distinction between reality and representation of reality, between what her characters are and what they wish to be, is crucial to an understanding of Moshfegh’s oeuvre because she’s not the kind of writer who lullabies the reader with self-indulgence. In her vision, there are no excuses to be found, just work to get done. Unlike the (so-called feminist) slogan, “Woman are perfect,” in Moshfegh’s stories, women happen to be very imperfect; they’re often liars, lazy, manipulative, hypocritical and unreliable, silly and cruel and ego-centered and yes, desperate. Far from fiction, women can lie for multiple reasons: historically to keep their man and more recently to keep their followers; either way the capital they secure for themselves as wives and as influencers is not a guarantee of freedom or happiness. And in any case, making excuses for female silliness is an old game that men like to play. “Among all the myths,” Simone de Beauvoir wrote in The Second Sex in 1949, “none is more deeply anchored in male hearts than that of the ‘female mystery’. It has many advantages. A heart in love thus avoids several disappointments: if his lover throws a tantrum and says nonsense, the mystery justifies her.” Mystery has certainly justified and made female lives a lot easier on the level of their public self, but has it made them better humans? Moshfegh’s answer is certainly not. That’s why her female characters are quite always delusional: because they’re part of the patriarchal game and they play it in order to take what they can get at zero cost, hopefully as soon as possible. Vanity’s mystifying power must then be addressed when it comes to the reality of female unhappiness: shortcuts don’t help and the silliness that might make a girl’s path smooth reveals itself to be a trap. The road taken, the one that looked more traveled, and therefore easier, might not be that easy at all.

For a long time Moshfegh studied piano, an art, she says, that taught her discipline and appreciation for greatness. She also said that she’s not intimidated by inspiration; in fact she just sits down and works. This is something we can easily perceive in her writing— all the work that she was willing to do in order to reach this facility of technique and meaning, the language with which she shapes her talent. In any case, Moshfegh doesn’t just choose words; she builds a very personal vocabulary for each of her stories, and in doing so her voice comes to the reader every time newer, fresher and more musical. It is no surprise that she’s now writing poetry. Hadn’t she already started with Lapvona? “The air was chilled between the trees, / no warm wind blew, / but the ripeness of the earth smelled sweet and musty still.” Recently, Moshfegh profiled Brad Pitt who recited Rilke to her: “You must change your life,” is the line that gives him chills. “Out here in California there’s a lot of talk about being your authentic self,” he told her. He’s quite right: Los Angeles, especially, is that city where everyone speaks of authenticity precisely because no one has it. Moshfegh never speaks of authenticity, she is authentic and doesn’t need to underline the obvious. If anything, she’s too honest—something that goes against her own interest—and as far as I can tell, this is no country (nor world) for honest people.

Italo Calvino once explained a simple and revolutionary concept: “I’m among those who still believe that the only thing that matters about an author is their work. (When it matters, obviously.)” This implies that whatever you may say about your bad book, it won’t turn it into a good one. And naturally, the other way around. It is also, I believe, where bad criticism over Moshfegh fails: when it lacks the ability to confront the text, and out of frustration retreats into discussions of her private life. Moshfegh is not interested in moral tales, nor has she ever expressed the desire to be a role model. On the contrary, she works to prove the banality of puritanism and the vacuity of a society that feeds itself with reassuring images when in fact “so much of our reality is delusional.” Ultimately Moshfegh knows exactly how to write the book that reviewers want to read; she just isn’t interested. To be fair, she doesn’t write to please the reader either—which is probably the only healthy way of writing in a compulsively consumerist society such as ours—and in doing so, she does. This is another reason why her writing is interesting: “Interesting, because not ‘crafted,’” Kerouac would say. “Craft is craft.”

And so this is Moshfegh: a writer who has structured her entire life around this art. You might not like her, but you have to recognize her devotion. Total devotion to something like writing requires a very special temperament, in addition to talent, discipline and a distinctive vocation for sacrifice; it leaves no room for self-indulgence. Rarely do you encounter someone who can honestly say it’s a nice path. There’s nothing fancy in the life of a writer. Much of it is a matter of faith. This is where Moshfegh admits to having faith the most: in the act of writing. And this is the way she’s offering her new novel to you. Lapvona neither saves nor finds anyone guilty, perhaps because everyone already is, and in the very end, Ottessa reassures us, it’s going to be fine: “death is the great equalizer.”