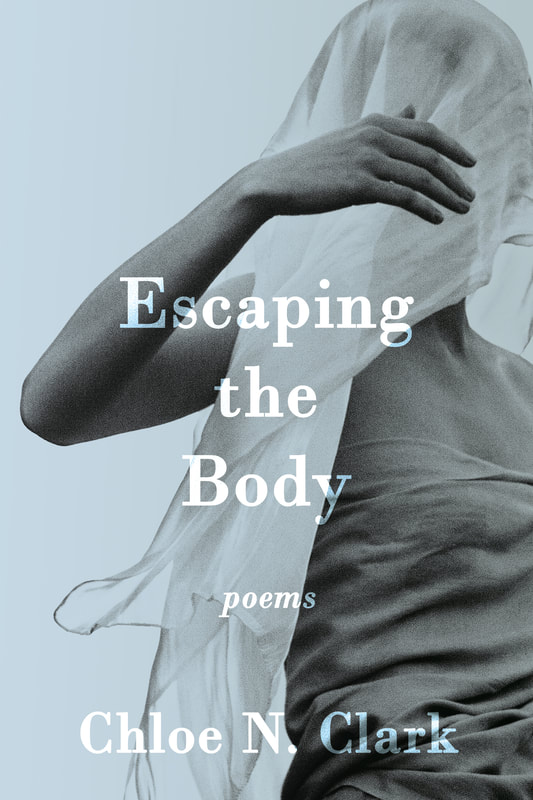

Chloe N. Clark is the author of Collective Gravities, Your Strange Fortune, and more. Her forthcoming books include Escaping the Body, Every Song a Vengeance, and My Prayer is a Dagger, Yours is the Moon. She is a founding co-EIC of Cotton Xenomorph.

Click here to order Escaping the Body

from Interstellar Flight press!

And be sure to read Chloe’s story “Waves Like Constellations”

from our first-ever issue!

What were your goals with your new collection, Escaping the Body, and what were your greatest joys in putting it together?

I think my main goal was trying to write a collection that felt true to being an individual inside a living body. I come back to sensory pain and illness a lot in my writing because at some level those are, unfortunately, some of the most universal things we experience. There are all these hoops we have to jump through — if we even get the opportunity to jump through them, with the barriers that so many people and communities face in regard to health care — in order to just feel well. But there are also all these other components of being alive that go around this — the joy of a body, tasting something delicious, touch, etc.

I think the greatest joy in putting it together was the chance to bring in all my magicians and escape artists. For going on two decades, I’ve been off and on writing a novel about stage magicians. It’s one of those projects that will never see the light of day and is worked on entirely for myself, so it was nice to be able to put some of that in these poems that I was planning to publish. Spread the magician joy a little.

In the poem “Once They Sainted a Mermaid,” you write, “when she wept it / tasted the same as the sea and so she never knew / when she was actually sad.” In magic, the audience has a unique relationship with knowledge; to a great extent, they’re consenting to being fooled. You also write about the Davenport brothers and how people exposed the brothers’ secrets yet still went to them and sought communion with the dead. What ways of knowing are you exploring in this collection, and how does the body—and perhaps escaping it — play into those ways of knowing?

I love this question! I think one of the biggest for me is knowing yourself versus the way others seek to know and explain you. So many of these poems try to tackle that idea and its twin: how we can never truly know another person. The Question poems in particular feel very central to this poem because they are set up as a series of increasingly detailed questions that seek to get to the root of those being questioned.

I know that when I was trying to write poetry as an undergrad, I thought the goal of a poem should be to impart some wisdom. Now, though, I’m drawn to poems that catalogue the unknowable. How do you find the voice or authority of a poem, to determine whether it should be asking, answering, or both?

I’m very called to the unknown. I’ve always been interested in how we talk about and navigate the unnavigable. So I think while that’s my passion, it’s also my authority. I don’t think I can 100 percent say I know anything about anything fully (with the exception, maybe, of limited-edition Oreo flavors). My authority is that I often know I’m not an authority, which means I’m usually asking something in poems.

You’re prolific, writing across fiction and poetry, and pulling from several different worlds, including outer space, the horror genre, and now magic. What appeals to you about working across genres, and how do you determine which world(s) to pull from for each project?

I think the simplest answer to this is that I don’t really think in poetry or fiction. My brain is often a big jumble of images and words, so I don’t really know what I’m writing genre-wise until I start physically putting it to the page.

For genres and worlds, I think a lot of times it’s also a process of discovery. I was steeped in folklore, sci-fi, magic, and horror as a child, and I think those realms have always hung about me. But I think they’re also all just really applicable to the themes I tend to find myself writing about — I’ve often joked that every story is either a love story or a horror story at its heart, and I stick by that.

For my story collection, Collective Gravities, it made sense to lean into space and horror themes because I was dealing with stories about connection and distance. For this current poetry collection, horror and magic felt truest. It’s about the horror and ecstasy of living in a body (in physical terms, but also as a body in space/time/cultures). So much of a magic trick (and even more so — escape artistry) is about pushing the body past its seeming limits.

I love what you say about every story being either love or horror! There’s so much love in this collection, grounded in the particulars of the body. Lately, there have been a lot of courses, craft essays, and anthologies dedicated to writing about sex. How do you approach writing about love and sex?

I think I try to get toward the emotional resonance of the act, like what is sex acting as in this scene or this poem and how can I make that feel tangible in some sense. It might be the descriptions of surrounding sensations or some memory that is stirred up. I think a lot of sex writing tries to be super visceral, but it comes off as X gets put in Y, and I always find it really boring. I remember working with an editor who had really big opinions about sex writing and their suggestions were very much against my intent, because they assumed if it wasn’t directly describing the body parts/act, then it wasn’t “raw.” Which strikes me as very uninteresting usually or at least not something I want to read (if you enjoy reading/writing that way, that’s great too! Because I feel like everyone should approach it differently).

For writing about love, I think I’m really interested in how love challenges us and compels us forward. Because ultimately a lot of our life is about who we love and how we love. So I always want to interrogate that on some level.

What challenges did you face in writing this collection, and how did you overcome them?

I think the biggest challenge is that it is very easy to just go full into the horror of something, but I’ve always wanted to balance that out. One conscious decision I made when writing these poems was to make sure to always include some elements of joy or light.

Why was it important for you to strike that balance?

For me, there’s not really a lot interesting about horror that’s entirely doom and gloom — a lot of more “arthouse-y” horror really doesn’t intrigue me because of this. Something like the film Hereditary had no stakes for me because it just felt bleak and cruel toward all of its characters, and I didn’t experience any emotional resonance with those characters either. Which meant it also didn’t feel scary. I think at some level, most of us have lives balanced by joy and horror, hopefully mostly in the direction of joy. So that balance feels truer to me as a writer, and also it makes me feel more emotionally invested.

And, dammit, I just really want to live in a world where there is joy and light in all this terrible that surrounds us. If I can hover in those moments, maybe the reader can too.

A recurring theme throughout the collection is touch. In “You’d Be Home Now,” you write, “there is a rush / in distance / in the long pull between / bodies who have found / one another but haven’t yet / touched.” That got me thinking about the rush in distance and the long pull between lines in poetry! Could you talk about how you approach line breaks and enjambment and how you know you’ve gotten it right?

Line breaks are something that I think a lot about. I think about them a lot because I think they are often really hard to explain because some of it is purely intuitive — this break just feels right. On the other hand, I think there are aspects that you can consider in regard to them: how do line breaks and enjambment help the momentum of a piece? Very short lines create a start and stop effect. Long lines maybe force the reader to rush past things. In what ways does that help the poem?

How are these breaks surprising the reader or twisting the perception of a line? It’s very close to how a prose narrative can build tension and subvert expectations. Line breaks give us this tangible visual way to shift how a reader reads our work.

And honestly, I never really know if I got them right — but I will sometimes surprise myself with the turn that a break causes, and that is always a delight.

How does your work as an editor and writing instructor inform your craft?

I think it’s constantly in play, even when I’m not consciously thinking about it. While my first drafts are very fast to write, I am a very methodical reviser to ideas in pieces. The process can take years. But I tend to revise less on structure or sentence-level craft, and I think that might be because while writing the first draft, I’m already bringing an editor’s focus to the words as they hit the page.

What does your revision process tend to look like? Were any poems in this collection particularly challenging to revise?

My revision process usually looks like me staring sadly at the computer for several years. That’s not just hyperbole. I think a lot of my revision is literally just rereading things over and over and then just constantly thinking about them, until I see the way they could reshape. And then I rewrite it to find that new shape. So often I don’t rewrite a single line, but instead an entire section might get scrapped. Or I’ll take a single line or image and everything else gets rewritten around it. In my collection Collective Gravities, there’s a 1,000-word story in there that started out as a 200-page novel I’d written. And then I just kept narrowing it down to what I thought was its actual essence.

In this collection, the poems that were based around questions tended to be the hardest because there’s an inherent kind of structure and pace to questioning. So if one question gets pulled, the whole thing can fall apart Jenga-style.

While you certainly use metaphor in this collection, many of the lines that one might expect to be figurative turn out to be things that were said in earnest. For instance, “The dead are speaking, a woman said to me,” in “This Has All Happened Before.” Or you take a speculative line and treat it as true: “On Wednesday, I find my teeth / sharpened while I slept” in “Little Skin Teeth,” for instance. What is the power of speculative poetry, of bringing in the unreal and having it sit at the same table as the real?

I think we all live speculative lives in some ways. Like just thinking about the fact that we’re living through a pandemic is kind of mind-bending in so many ways. The strange so often becomes our everyday, because so much makes us live outside ourselves in some ways, whether it’s grief or love, or whatever. So, in a lot of ways, I think speculative elements can more accurately depict what our emotional and mental states are at any given space or time.

Do you have a favorite magic trick? Or a bit of everyday magic?

I love all magic tricks, from the very small to the complex and giant. Since I was very young, I was obsessed with Harry Houdini’s escape artistry, and that turned toward stage magicians, as well — particularly Jean Robert-Houdin and Howard Thurston.

I think my favorite magic tricks, though, as someone who appreciates simplicity, tend toward card tricks. Nothing fancy is needed, so they’re open to everyone, and they still give you a glimpse into what could be — this two was a queen all along, you just need to look closer.