I should have noticed sooner. After all, I was the only person without PhD behind their name who still tried to talk to him.

I’ve picked up a reputation for being observant: who let slip that the meeting with their supervisor didn’t go as “productively” as their eyes said, who let their failure to get with distinction sting at the edges of badly shorn hair. We all move through academia differently — I focus on the minutiae because if I don’t, I’ll fall through the grandeur.

I latched onto the knowledge that we use the same pen — 0.5 black ink — like a vine. During orientation, seated next to each other in the cramped auditorium, I joked that we’d never know whose pen was whose now. It wasn’t funny. He still gave me that breathy laugh you give when you’re trying to be polite. I took it anyway, trying to get as close to him as I could. I always sat across from him in seminar, watching him with rapt fascination — I’ve never seen someone so assured of what they were saying.

He quickly became what our colleagues called “the department darling,” a draining presence whispered about over weak coffee. While we stammered over oral exams, he breezed through them in both English and German. While we got desk rejection after rejection, he published his third peer-reviewed article by the time he reached candidacy a full four months ahead of schedule, the department head barely able to contain his pride in the glowing congratulatory email he sent us.

The jealousy permeating our college quickly morphed into resentment, a simmering stew of indignant glances and stiff smiles, laid thicker than the summer the air conditioning leaked. Not for me though. He filled me with strange wonder, the kind that twists envy into awe. By the time I — and everyone else — became candidates, he was three full chapters into a tome of a dissertation: a sweeping body of work that didn’t just fill the gaps in the literature. It expunged them of their past mistakes. He made waves far beyond our little college, flying around the world to give keynotes and clink drinks with the very thinkers we feverishly modeled ourselves after. He single-handedly propelled our reputation straight into space — our head was downright gleeful the day we learned we were now the #1 grad program in the field in both Canada and the U.S.

My mother liked to remind me that nothing comes for free — a fact I grew to resent as my funding dwindled. I thought I saw how much everything must have cost him by how anyone who wasn’t tenured — or at least on that track — treated him, surrounded by praising professors at every function while desperately looking for someone to actually see him. I tried to be that someone for him, inviting him for drinks with eyes rolling behind me. He always said no but I never stopped trying. After all, I was the one who took his phone and put my number in.

I should have noticed sooner.

I don’t leave people behind, even if that’s where they’ve left me. I’ve always extended my hand first, bracing for the chop.

He came back from a conference in Berlin so pale-faced he looked like he emerged from a pile of ashes. He waved my concerns away, saying it was just jet lag. Jet lag doesn’t make your cuticles recede like that, or carve into the skin around your eyes, or blacken your gums no matter how hard you try to talk without showing your teeth.

I used to have a reputation for being observant. I don’t know how I missed how terrible he looked whenever he left to fly off to another conference, or how much he glowed after he got out of a meeting with his dissertation committee, or how he became even more radiant after a quick stop at the head’s office. Or why, eventually, the more “advanced” students in the program stopped showing up to after-term drinks, and then department functions, and then the classes they taught, their students listless in their seats. “Some people never officially drop out,” we told each other. “They just disappear.” Family obligations. Health issues. Lack of funding. “You know what academia does to you.”

There was an assistant professor — teaching stream, if I remember correctly — who didn’t resent or praise him for his accomplishments. “I pity him,” she told me over a glass of chardonnay, away from the other professors at yet another department book launch. “You don’t get all of this without paying.”

“But he doesn’t,” I said stupidly. “He won another $35,000 scholarship.”

She smiled at me, the corners of her eyes all flat. I’ll never know if she pitied me, too — she left that semester, her position up for internal hire.

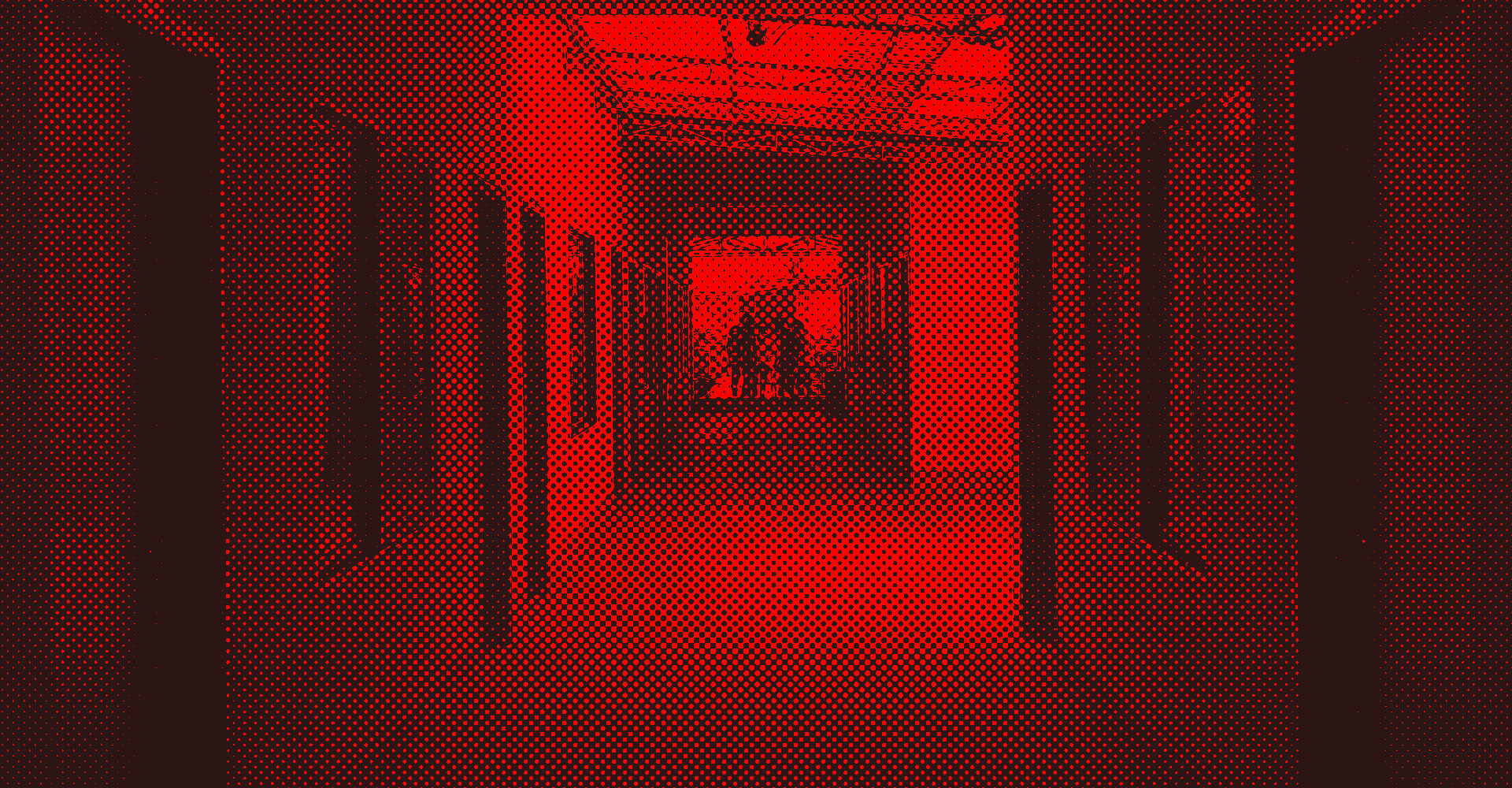

I should have noticed sooner. Three months after he got hired and about a week after I became the last person in our cohort still in the program, he asked if we could meet. I knocked on his office door. It echoed pathetically in the empty college. When he opened it, I staggered, his entire body exploding with the kind of light I’ve only seen play across his face all those years ago in seminar. He gestured me in, his hand aflame, but I stayed back, finally listening to everyone else long after they’ve gone. He laughed, a high ringing crackle, before sitting back down behind his desk.

“How’s the dissertation coming?” he asked, wiping at his mouth.

I didn’t look at him, too focused on the acrylic cup full of 0.5 black ink pens — telling myself that there are many reasons why saliva looks like blood, and knowing that there aren’t.