Review // by Julia Kooi Talen

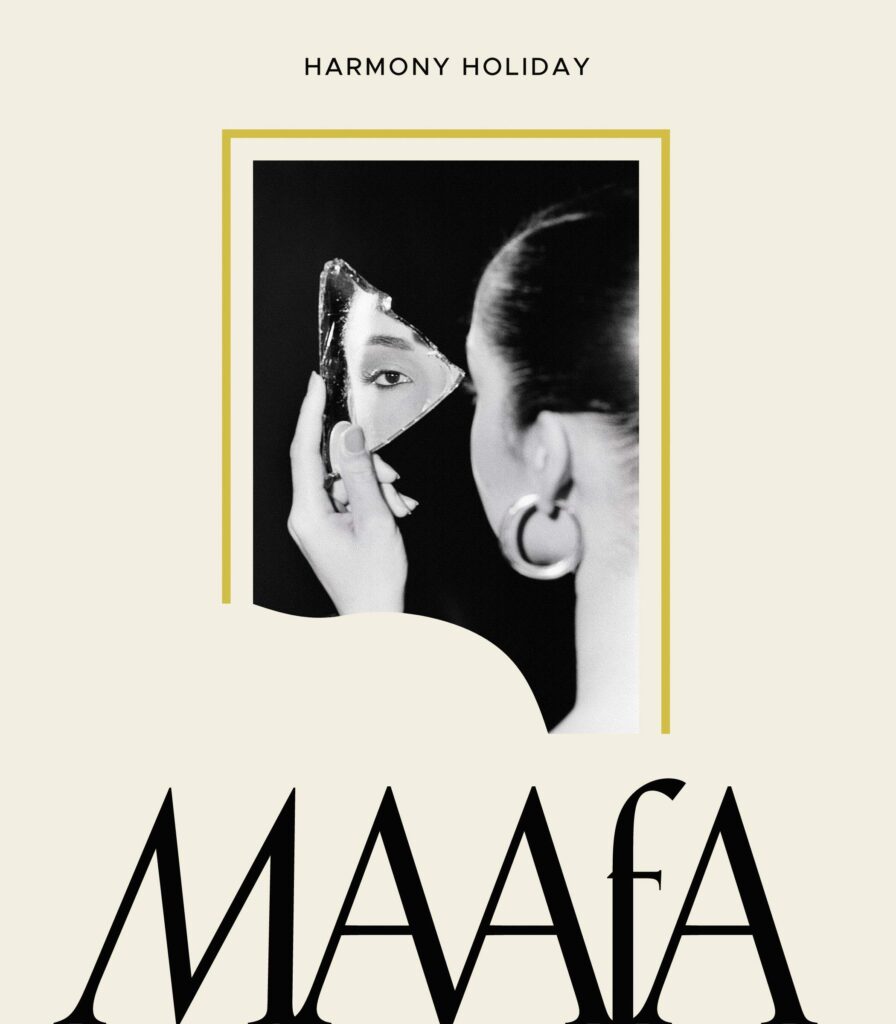

Maafa by Harmony Holiday

“Not that I was violently inherited

But that nothing has ever existed unless it’s been ruined into proof of life”

Published by Fence Books and out this month, Harmony Holiday’s Maafa defies the constraints of genre by composing an electric assemblage of lyric essays, prose poems, verse, and images. Often repeating the words “not that” within its body, Maafa unerases the centuries of broken Black existences that it simultaneously attempts to hold space for, connect to, and reinscribe.

In Holiday’s book, the protagonist, Maafa, is both the catastrophe of the African holocaust and a young girl in pursuit of freedom from all that hovers around and within her — shame, grief, eradication, trauma, and longing. Holiday’s billowing text and the connection its living stories have with inherited memory can be likened to one of Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Rooms, a kaleidoscopic art installation project that feels like an endless expanse of interconnections and reflections. This expansiveness mirrors the shortcomings located within the singular Swahali word, “Maafa,” defined as catastrophe and often used to describe the African slave trade. How can a word hold space for such a rippling disaster and aftermath?

If anything, Holiday’s book feels like a stronger definition for the five-letter word because it strays from the confines of a boxed in explanation or experience. Repetition continuously haunts Holiday’s poetry through an echoing of redefinition. It journeys across human bodies, bodies of water, bodies of land, and through the underworld. We transverse linearly through the text, but Holiday’s poetry encompasses all temporalities as Maafa attempts to exercise herself of all that harrows her.

While moving through Holiday’s epic, the author’s ties to both music and dance quickly becomes evident. Holiday’s attention to sound in her stretched-out lines mimic a chromatic scale progression, a series of evolving sonic semi-tones. The lines serpentine, words likening to old layers of skin, shedding into new layers, and evolving with Maafa’s journey:

“Catatonia, my tongue is slipping down my throat as the serpent lips my spine / which is stippled too into the new arrowroute green note la luta intoned & coaxed honor / bending in every endlessly sturdy austerity ecstatic (you won’t need those chains) / speechlessness the place where thought collects as hive and hides effort in the / force of grace”

Here, tongue becomes lips becomes spine. Sound is stippled then made green. Hives become hidden, and we feel the sensation of endlessly tumbling through language, through its aural folds, its dimensional chronologies, and its perpetual limitations.

The myriad of shapes and textures woven into this collection further accentuates Maafa’s multitudinality — both temporally and spatially. She fractures, fissures, stretches, negates, escapes, just as Holiday’s lines, paragraphs, sections, and words do. We pass through the book in sections titled: Preface (to a neverending genocide note), SAY HER NAME, Duat, Leitmotif (Run), and Paradise of Ruins. The sections reflect the simultaneities in the text, Maafa, by seeing the term, the title, and the character all as a genocide note that never ends, all as spiralized narratives that ebb and flow. Each poem, each lyric essay, overlaps, connects, exists in the preface and in the ruins. Holiday writes in “Maafa’s Narratives of Progress”:

“I thought it would be a moaning place not a screaming place an alimony to suffer /

forward leave the mother in her shamble of joes and bills her lilting green going

Now I don’t see much difference between ownership and hysteria even when all you own

is the narrative and its never-telling holding on to this unconfessed torment like a secret love /

of ruin and bringing it to life endlessly as a private need for ruin not to punish /

but to begin again to haunt with renewal.”

This “haunt with renewal,” this “narrative and its never-telling” suffuse Holiday’s text. The book’s cover haunts its pages too: a Black woman looks at her portrait in a broken piece of a mirror, her reflection gazing back at the reader. Oftentimes, Holiday embeds large spaces between words and lines into the field of her poems. The lines frequently pull across each eight-inch page just as Maafa stretches across the world and through time. These spaces can be read as line breaks, word evolutions, or gaps. In conversation with poets like M. Nourbese Philips and Layli Long Soldier, Holiday positions her language on the page and adds subtle layers to Maafa’s story — one of diaspora, blood, and a chase towards freedom.

Holiday also weaves in photographic and scanned images throughout the final section in Maafa, titled “A Paradise of Ruins.” Holiday presents a photograph of Prince, various wanted ads for slaves who have escaped, finally ending with a fuzzy photo of a young Black girl, perhaps the “I” that manifests throughout Maafa’s story. The relationship between images and text not only pairs Maafa with the speaker of the poem but also to various Black figures and contemporary Black images. Placed directly behind the blurred photo of a young Black girl on the following page is another wanted ad — $700 for Maafa. Positioning these two images, back to back, reiterates the overlaps in the various women, I’s, Black women, and Maafa’s, existing in photographs, in historical documents, between each page of text and time. Moreover, the images of both known Black figures and the fuzzy photo of a young Black girl recall the cover, a scrap of mirror reflecting a small fragment of the Black woman.

Because of the numerous ways in which Holiday’s text invokes a rich, hybrid multiplicity, it prays to be read and reread so that reader can feel the weight of its expanse and glean new, ground-breaking insight. Each detail — a gap between two words, a line break, the position of the text, or an image — deserves our attention. With astounding determination, her text concentrates and meditates on the numerous minutiae that text can embody — sound, space, shapes, structure, relationships. By brilliantly realizing and excavating a resonant exploration of Black history and identity, Holiday’s Maafa ultimately resists erasure. Maafa’s never-ending story endures.