Generative Revision: Unexpected, Gorgeous, Messy

by Kate Finegan

Writers revise. You’re a writer. Open your eyes and see anew. Be willing to amaze yourself. Be willing to stretch in both directions at once. You won’t pull apart; you’ll break open into a rainforest of unexpected, gorgeous, messy life.

Laraine Herring, Writing Begins with the Breath

Craft Notes

In high school, I was always, always in the theatre. Before the morning bell, during study hall, every weeknight for rehearsal, every Saturday building sets. Because it was public school in Tennessee, and it was the arts, we had to be just about entirely self-sustaining. Our five-dollar-a-pop tickets had to fund the cost of each production, so we saved every screw that we removed from the sets at the end of the run. Every show was planned with an eye toward what could be repurposed from the workshop and props and costume closets.

There’s an old saying that theatre can be made with two boards and a passion.

The magic happens in the space that’s made and remade; there are endless ways to fill that space. In the same way, I like to think of first, second, and sometimes even third drafts as my two boards—the raw stuff I have to work with. Those boards may have been put up with a passion, but I have to bring that passion to work every time I show up to the stage, or page.

Collaborative arts—theatre, dance, music, film and television—are iterative processes, in which each new idea is the springboard for something else. An actor gives a new reading of a line, or adds a bit of business with a prop, and it works, so that has ripple effects throughout the piece. We as writers can harness this sort of iterative, additive process through generative revision.

Generative revision happens before editing. It’s a process of fanning the flames of what’s working in your piece, of tossing in stones and following the ripple effects. It involves writing into and beyond what’s already on the page. It can lead to major changes; it can lead you into territory that feels more vibrantly alive, more true. Sometimes, that territory is not comfortable. It can end up feeling like a conversation with yourself, a process of looking inside, as well as out, even if you’re working in fiction. It can lead you down uncharted paths and make the work seem even more tangled.

The unsympathetic poet enters into the frightening territory of writing the truth of who she is and sees, regardless of the acceptable or admirable norms she’ll find approval in. When we enter into this realm of unsympathetic we sacrifice our desired self image in order to provide what very few do: truth.

Robin Richardson

Writing into the truth of a piece takes time and space, and working within an existing draft doesn’t provide either. This weekend, we won’t be talking about taking out your red pen or tracking changes, which are part of the editing process. Approaching revision from the place of a full page is like trying to stage a brand new play at the same time that Hamlet is being performed.

Generative revision offers you an empty stage, a couple boards, and endless space for your passion to unfold. Often, this is a process that taps into what’s been percolating underneath conscious thought. We often think of the first draft as the place of freedom, where the pen can run wild, but I have often found this is not the case. When I’m writing the first draft of a fiction manuscript, I am thinking about what needs to come next, what I’m trying to say; I am often very conscious of creating a thing that needs vibrant characters, tension, and logic.

The draft is a thing, so I respect the thingness of it. Generative revision involves writing a lot of words that are not a thing; that are likely to never live outside your notebook. In the locked space of the blank page that isn’t expected to see the light of day, your subconscious can come out to play.

I’m a big believer in the subconscious being a part of the process. My brain is working on problems constantly, even if I don’t even realize it. If I let my subconscious work on something long enough, solutions just pour out.

Carmen Maria Machado

In Writing Begins with the Breath: Embodying Your Authentic Voice, Laraine Herring claims that “part of your job in the prewriting phase is to maintain a consistent curiosity about your work.” I would argue that curiosity is also deeply important in revising a draft. In this phase, you are guided by curiosity about what’s simmering beneath the words, about what forms this work might take, and how you might push it fully into the light that it’s reaching toward.

You will never be as smart as your subconscious—it’s three steps ahead of you at all times.

Jill McCorkle

If you’ve taken a Weekend Workshop Intensive with us before, you’ll notice that this one is a bit different. Because it’s focused on a stage in the writing process, as opposed to a craft element, there are not as many recommended readings, although you can click on the quotation citations to read where they came from. Instead, you’ll find a lot of questions and tasks to guide you as you dig deeper into a project you’ve been working on.

Questions

How do you determine that a draft is worth revising?

How do you manage your drafts, in a practical sense? Where do you put all the cut lines, scenes, and images? What about all the freewriting you do?

How do you deal with revision fatigue? How do you maintain your energy through revisions?

How do you decide which parts of the draft need fine-tuning and which should just be scrapped?

How do you make big changes in subsequent revisions, without the final work feeling pieced-together or scattered?

Exercises

If you’re not quite sure what you want to revise this weekend, go through an old notebook or some of your computer files. Assume the air of someone at a thrift store or garage sale: search for gold, discarding all else. Read the notebook or computer files without an eye toward the context of the pieces as wholes. Instead, just look for bits of language that surprise and delight you, that make you feel something. Circle or underline these.

If you know what you want to revise, do the exercise above, but focus only on that one piece.

And if you’re working on a collection, go through this process with your collection!

Read through all the bits that you have circled. Write down any recurring or particularly effective images. Read those images. Ask yourself: What story are these images telling?

Write that story, in one sentence. This is the heart of your piece. We’ll be writing from this heart.

Recommended Reading

Toni Morrison, The Art of Fiction No. 134

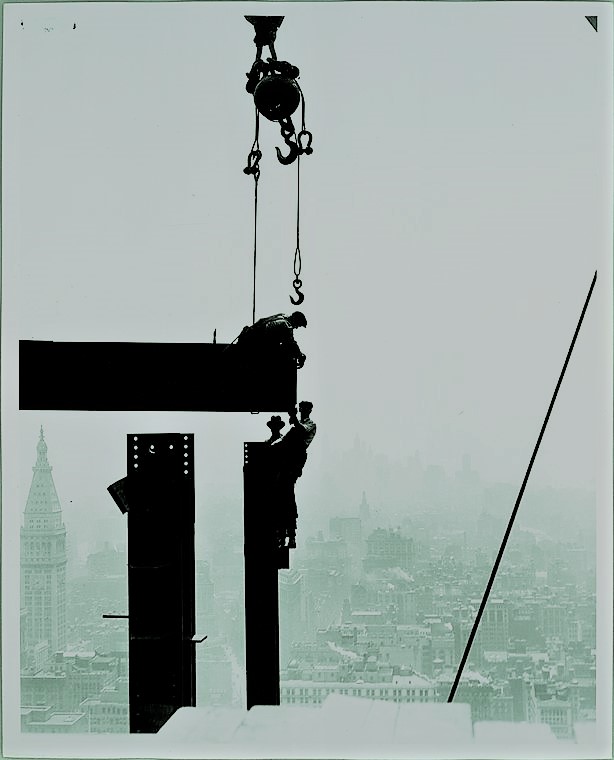

Image from the NYPL Digital Collections