There’s a knife in Mae’s hand that works like warm butter. It never goes after anybody, unless you count Mae. And you shouldn’t. You should never count Mae. The self is a different kind of victim, a different kind of stalker. You don’t have to take my word for it though, just ask her. Mae, I mean. She explains it better than I ever will.

Mae’s been cutting off pieces of herself since she was small. The mosquito bite on her Achilles, gone. The thick patch of eczema on her left shoulder, peeled clean. That one tattoo she got at Myrtle Beach when she was drunk on shitty cocktails, expertly whittled from her rib. And her eye. The purple-black bruise he left her with. It was the finest cut I ever made, she told me one night. I understand now, all those years of practice. I understand.

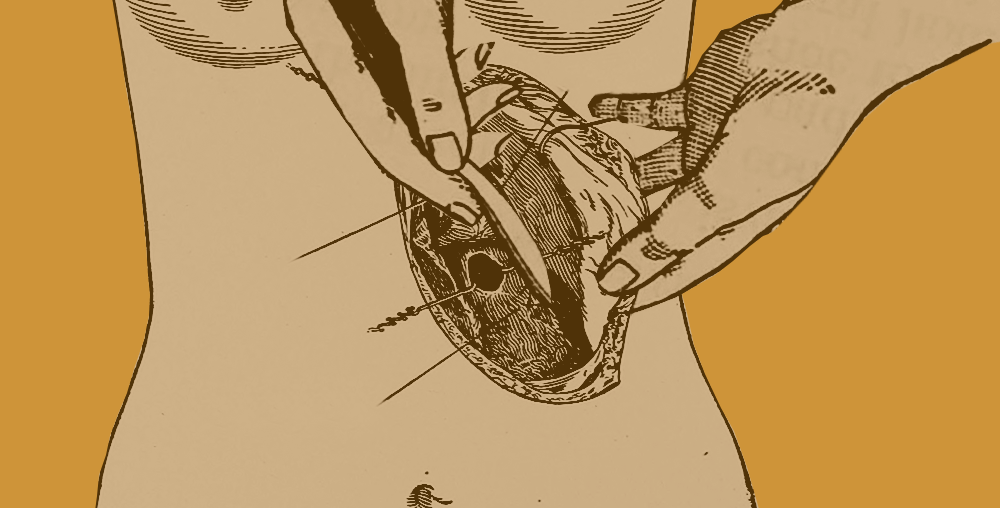

My nails were painted yellow the night Mae woke up with the panic in her stomach. I didn’t understand at the time. The panic was always in Mae’s chest, you see, not her middle. I watched it grow, swollen with terror, shaking and tearing at Mae’s body. We need to get it out, I told her. Whatever it is, we need to get it out.

I know what it is, it’s my panic. It’s ok though. You’re here. And so is my knife.

The truth is, and I’m embarrassed to admit this, but I’d never seen Mae use it. Her knife. The knife. I wasn’t even sure what it looked like. She’d cut cherry tomatoes into halves on the kitchen counter, and I’d ask silly questions like, Is that it? But Mae’s always been patient. She’d smile and say No, my knife’s smaller, very clean, and place the bigger half of the tomato on my tongue.

I watched as Mae reached out, back stuck to the mattress with cold sweat and our own shared bodies, the way we fell asleep before rinsing, let the mint sheets stick dirty to us in the aftermath of our crying out, wet limbed and full breathing. Let me get it, I said. Her fingers grazed the handle of our nightstand.

No, she said, only I can touch it.

It wasn’t possession, a demand made through veiled accusation or hungry ownership. Mae said it as fact, as a warning. Be careful.

I think it was beautiful. Hard to tell with the lights still off, our eyes only half adjusted to the dark. But I think Mae’s knife was gorgeous. Clean. Just like she’d told me.

Give me some room, Mae said, and I crawled to the tip of our mattress, watched as she dipped the knife into where her belly button sat, open-mouthed like a crater on the moon. Mae was right about the warm butter. I had never quite gotten what she meant by that, until I saw the way her skin rippled, the neat folds it made as it curled back and back and back. Warm butter, not melted, she told me once. The distinction is very important. Mae’s stomach was a tote bag, a Mary Poppins purse. I don’t know how else to describe it. The things she pulled out, one by one, Mae’s breaths calming with each new discovery: her old wedding album, the French press, her deceased mother’s aloe plant, the matching dishware, the tapestry from Czech, elephant bookends made from iron, the divorce certificate, his apology note. And then the last and final discovery—Jesus Christ with His dreads wrapped tight, the bun on His head sagging from the weight. He prophesied in between bites of fish and rice, the banana leaf still steaming, while Mae took long breaths of cool air and I stared miles into the now empty place where Mae’s stomach once kept panic, confiscated from the grain.

In the morning, I found Jesus at our dining room table, drinking coffee. A dark espresso roast. Mae was outside on our porch, picking basil from the flowerbeds. The oven was on, the smell of bread rising. A pot of sausage gravy on the stove. Christ said good morning, and the anger in me rose with the bread. I glared at Him. “Why are you still here?”

His dreads were loose now, free of His bun. They blanketed His shoulders, tiny buds of pink and yellow, winking. He put his coffee down. Stared straight at me. I was not expecting the sadness. “I understand why,” He said, “but I wish you wouldn’t assume I’m here to ruin something.”

Mae came in from the patio, sure to close the screen door behind her. Mind the cat, she told Jesus, and kissed me on the cheek. Biscuits are in the oven. She stopped. Looked at my face. Don’t worry, ok? Really. There’s plenty to go around.