Dear Uncle Stewie,

There’s so much I would ask you if I expected an answer. You never spoke in life, let alone wrote letters. The tumors that grew along your spine and in your brain prevented language, the tree that flowers in me, from ever taking root there. Now and for these many years, you have been among the dead, also known for their great and terrible silence. But I’m writing you.

It is my profound hope that you will gain from these letters, that in some way you are reading them. That though death continues to deny you speech, it has granted you literacy. In studying Tractate Avodah Zarah 3b, we learn, “What does the Lord God do with the last hours of the day? God teaches the children that have died.” So we’ll talk as two learned Jews to each other. I have been lucky to learn with many rabbis, but it seems your Teacher surpasses them all. I sometimes worry, though, that the lessons God oversees are cruel and demanding.

My mother sends her regards. She was ten when you died. She has grown into a woman of incredible compassion, a fierce lover of justice and a brilliant thinker. She rarely mentions you without crying, which is odd, because she tells me her favorite memory of you was your laughter. “The most beautiful laugh,” she says. I hope wherever you are, it is filled with the sound of that laugh, of the joy you shared with her. She has much reason for joy these days. My nieces and nephews are growing strong and beautiful, keynahara, and Mom gets to spend many days a week with each of her grandchildren, Baruch Hashem. Sometimes I worry my sisters take a little advantage of her constant hunger for time with them and get her to babysit when she’d be better off resting. But she’s happy, I think. Like your mother, my Grandma Bea, sometimes my mother has an air of deep sadness about her. I suppose I have it too.

I’m doing a lot better these days, but there was a time when that sadness got the best of me. I was so miserable. I was in so much pain. I wanted to die. I tried to die. So I ended up in a residential care facility. I was in in-patient for a year, about twelve years ago. I guess that’s why I’ve been thinking of you so much, Uncle Stewie. It’s been twelve years since I got out, and it only just occurred to me that I’m the second generation of the family that saw the inside of an institution; the dull beige walls, the loneliness of a bed that could be anyone’s bed, the chafing of not being able to leave.

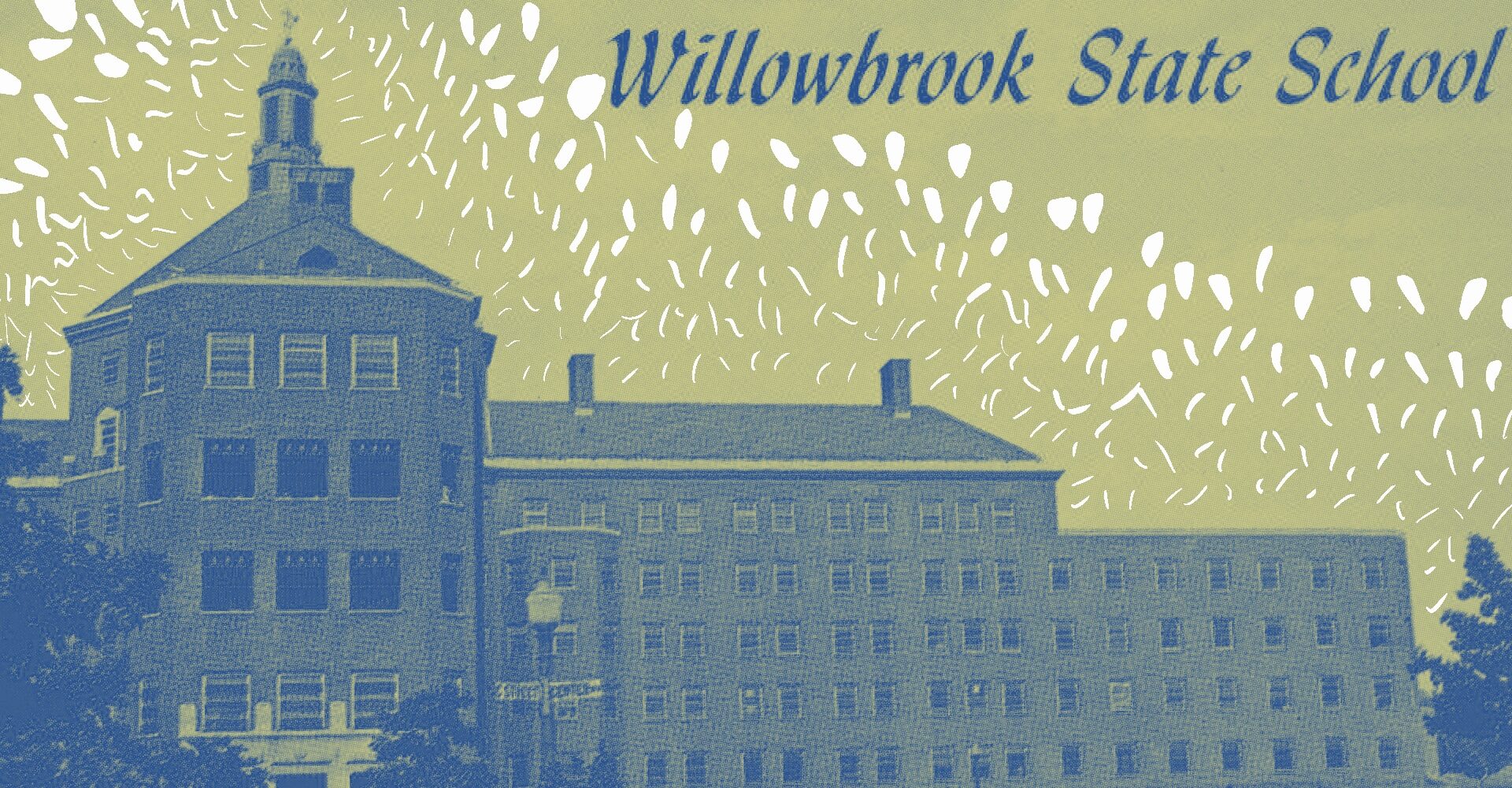

I hope you won’t be offended by the comparison. I am aware that the cushy, private, residential, farm-work-based therapy program I was in is a far cry from the horrors of Willowbrook. I read that in 1965, the year before the year you died, Willowbrook had 6,000 residents, 2,000 more than its 4,000-person capacity. Conditions were fetid and rife with human incompetence and abuse. In 1966 you died, from pneumonia, possibly as a result of force feeding. Six years after your death, Geraldo Rivera’s Willowbrook: The Last Great Disgrace premiered, lambasting New York State for the facility’s excesses of mistreatment and “warehousing.” The resulting lawsuit proved formative to civil rights legislation for institutionalized people, and Willowbrook closed the year I was born. I am, in every way, part of a new and different era of institutional life.

But I wonder what we shared. I wonder about the boredom of institutions, the way the hours tick by slowly. I wonder about the envy and fear of social workers and other employees of the institution, who can come and go, who have a life outside. I wonder about your laugh, Uncle Stewie, and what made you laugh in the hell of Willowbrook. I wonder what made me laugh when I was in the hell of my own mind. The words I could write when I was sick were such a comfort to me. What did you do, without them? I hope one day I’ll know.

Love,

Your nephew,

Mordecai

♦

Dear Uncle Stewie,

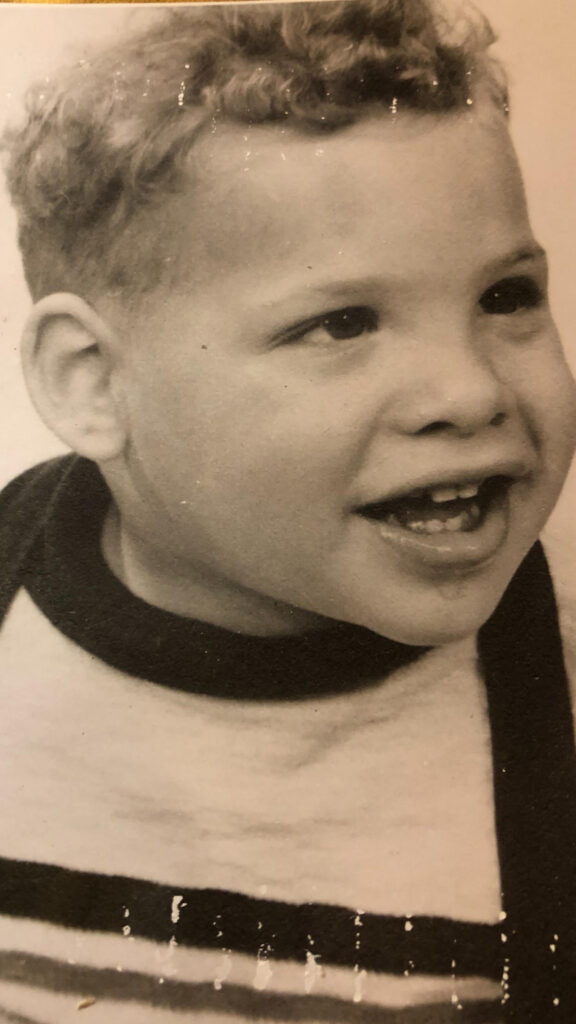

You were only a baby when you were diagnosed with tuberous sclerosis. Still, I wonder what you felt, as a child, in the dark of the examination room, as the Wood’s lamp warmed up, casting its eerie blue glow. Were you able to focus your eyes enough to follow its path along your body, highlighting the tumors under your skin? I’m told that the tumors typical of tuberous sclerosis look like ash leaves, which is to say, like spear heads. I wonder which image you would have liked more: a peaceful canopy of ash leaves under the skin, or the marks of a dozen spears. Now that you’re dead, I prefer to associate peace and growth with you, but you were a cheerful little boy, and cheerful little boys always seem to have a touch of the morbid and the war-like in them, and who knows, maybe spears would have appealed to you.

My own first diagnosis came at age nine. The diagnostic standards of ADHD require dull, repetitive activities to draw out the extreme discomfort with boredom and concentration typical of the disorder. Long hours in a child psychiatrist’s office to prove what exactly? That I hated spending long hours in psychiatric offices. Too bad, there was more of it coming.

I’m unsure why I was being tested for ADHD when what I really was was unhappy. That year, my two best friends had learned the adolescent habit of mocking those they care about. I didn’t understand why all of our time together now revolved around pointing out and laughing at my flaws, and I didn’t care for it. I was physically bigger than the two of them, so I took to exerting my size to express my displeasure, roughhousing and beating them, which I’m sure they didn’t care for. Eventually, my teachers noticed that I was becoming something of a mournful bully. They told my parents, and I found myself in the brown suede chair, organizing blocks over and over and answering anodyne questions about what I liked to do.

Sometimes, diagnoses are like first kisses: both a culmination and a beginning. Just as it’s difficult to pinpoint that first moment when you want to kiss someone, find them desirable, hope they want you as well, so too is it difficult to know precisely when you begin to suffer, when a fear becomes anxiety, when sadness deepens into depression. And just as first kisses are erotically and romantically tinged with everything that can come after — sex, a relationship, a marriage, children, a life spent together — so diagnoses borrow gravitas and tragedy from all they imply: struggles with symptoms, treatment and its side effects, and of course, death. Even diagnoses that should by all rights be framed as “good news, it’s just this” come shaded with the near miss of “I’m so sorry, I’m afraid it’s that.”

Then again, sometimes I think that all that gloom and doom of diagnoses only really applies to our loved ones, who feel lost and sad that they don’t know how to approach us now that we have been marked as “sick,” “disabled,” “Mad.” We are suddenly very far away, off in a land of doctors and medications and special facilities. But to us — the diagnosed — we are never far away from ourselves. The intolerable haze of boredom, the spears underneath my skin, are right there, red hot and piercing.

Or maybe, Uncle Stewie, I should remember that even those spearheads can be ash leaves, a rich shady canopy that I could lie under for hours. Your dappled skin was a symptom of your silence, rich and vast and punctuated by your laughter. For now, I’ll join you there.

Love,

Your nephew,

Mordecai