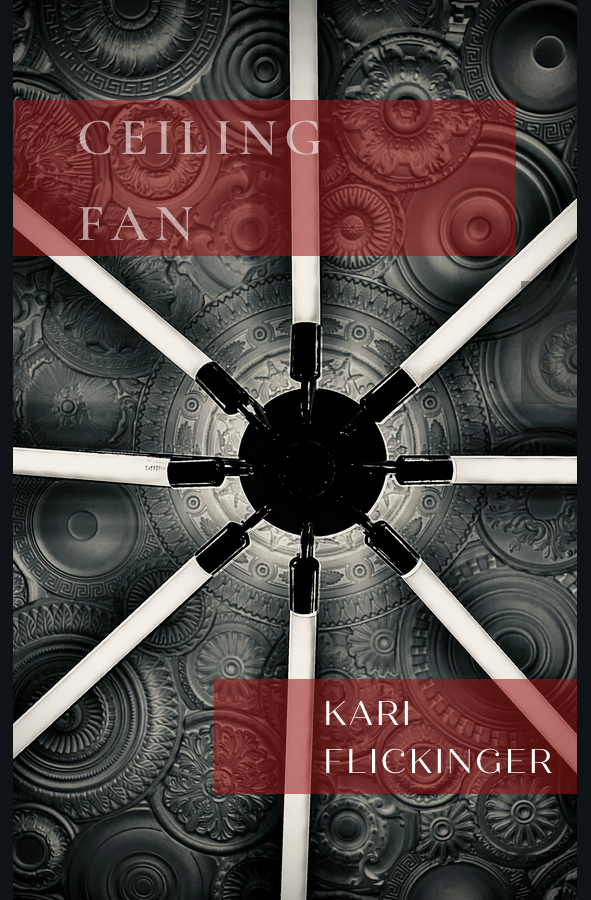

Kari Flickinger is the author of The Gull and the Bell Tower (Femme Salvé Books) and Ceiling Fan (Rare Swan Press). Her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, Best of the Net, and the SFPA Rhysling Award. She is an alumna of UC Berkeley.

Click here to order Ceiling Fan from Rare Swan Press!

And be sure to reread Kari’s poem “You Swallow a Super Moon and a Doctor You Have Never Met Prescribes Prednisone” from our spring 2020 issue

First, some questions on process: do you have any writing rituals that help you in the generative portion of the creative process? How about when you revise?

I mostly just trust my instinct when an idea comes and try to jump on it, immediately. Sometimes this has meant writing on sticky notes in a crowded room or locking myself in a bathroom stall to write. I have a notebook with me always. For revision, I talk to myself about the work. Saying the poems aloud can help to get that rhythm down, or to hone the repetitions. If it’s conversational, it’s probably more genuine too.

Do you write from experience? Are your poems personal, observational, a bit of both?

Both. Ceiling Fan is mostly personal experiences. There’s a line in there that someone said to me over the phone when I was working at a call center. Mostly, I do write from personal experience, but I observe a lot to try to funnel that experience into something more than my own. It can take me years to translate experience into tangible meaning.

Did Ceiling Fan begin with an idea or a selection of poems that morphed into a cohesive whole? Or, did you develop the arc of a message you wanted to explore before you began? Was it somewhere in between?

Ceiling Fan wrote itself in a few afternoons. I wrote around it for about ten years, but it was a fully formed little being when it came. I edited as I went.

The exclusion of individual titles created a conversational and more stream-of-consciousness tone, where one poem leads into the next in a way that would have been disrupted with titles – was this intentional or did it grow out of the collection as you wrote or revised?

This is intentional. If I were to give the pieces titles, it would simply be that first line. I like the whole thing to read as one. My editor really supported this decision too.

Several images (the ring finger, modern phones with their lack of a receiver, a cat, and the moon) that appeared in your Longleaf-published and Best of the Net–nominated poem “You Swallow a Super Moon and a Doctor You Have Never Met Prescribes Prednisone” reappear in this collection. Was this intentional? Do you find you have favorite images and metaphors, or do you work through them to a point before moving on to others?

I have a core list of images that I tend to work with, and I’ve imbued them with great meaning within my own writing constellation. I think most writers do. We’re symbolic creatures, and sometimes certain symbols speak loudly to us. I even went so far as to make a generative set of cards out of them to better understand my own repetitions. I based this on Michael McClure’s personal universe deck and organized them by specific senses. It’s like making your own generative tarot. Maybe understanding our repetitions is how we can best find ourselves.

When you began writing Ceiling Fan, did you want it to be entirely separate from your first collection, The Gull and the Bell Tower, or did you consider it as more of a deepening, with a connection to the first? Something different altogether?

I didn’t set out with aims for Ceiling Fan. It just wrote itself. The Gull and the Bell Tower was broad and covered a long period of time that was all connected by similar feelings, while Ceiling Fan focuses in more closely, to say something new about processing some of those feelings.

Blank space holds power in general, but as Ceiling Fan explores the theme of absence — be it in blinking light, dots and dashes, gaps between fan blades, or even a break in the speaker’s voice — how did you decide where the blank spaces should be in this collection?

I was very intentional with placement of space, though some changes have been made with the guidance of my editor. I aim for conversation. I want it to read like it’s being whispered in its entirety from a strange voice over a phone with a bad connection. Moments of silence are as important as moments that run along the page.

Although gaps or absences offer unlimited space for exploration, you expanded the topic through the addition of intermittence. A ceiling fan captures the recurring or even rhythmic return of absence in love and identity formation. Does this theme apply to your writing and publication practices?

For publication practices, I think yes. It’s feast or famine, often. For writing, I hope also yes? I like the idea of being a liquid being in the face of cycle recognition, but I worry that my own rigidity affects most relationships. Including my own relationship with my writing.

A powerful moment in this collection is when you say you are “not/a syncopated being.” With this in mind, how much do you focus on individual words and their meanings? Do they just come to you and feel right, or, for important moments in your writing, do you investigate definitions and etymology?

I love this moment because I’m a former musician. So, being inside the framing device of a rhythmic fan and finding myself outside of the music of the fan is such a hard place to be. I often look up etymology and investigate definitions. I find myself down rabbit holes pretty often. I have schizoaffective bipolar, so it is easy for me to get lost on tangents of perceived meaning and try to force it to make sense to others. Collecting evidence is the best way to bridge understanding.

Ceiling Fan interrogates loops, which begins with the ability (or inability) to notice the existence of loops in our lives. Noticing and attention are among the greatest objectives and capabilities of poetry. But as your collection points out, a ceiling fan is not just about noticing what is there but also what is missing. Has noticing the loops played a part in your career as a writer?

Yes. I had quantum cosmology in mind with the loops. Loops in this context do perform many functions. I think one of the most interesting things they do is lead to expansion and contraction. If you watch a fan for a long time, it becomes one mass, or just space. Taking this idea, though, the viewer matters as much as the viewed object. This can also simply mean, looping back to people, ideas, or feelings. Looping back to feelings, images, ideas is what has defined my writing. I like to think I freshen it. But really, I’m just trying to better understand the same moments, the same feelings, with new definitions.

Toward the end of your collection, the speaker questions rumination and utilizes writing to exorcise rather than “to bring anything back.” Does the collation of an entire collection differ from a single poem in achieving this end?

A single poem can tell a story, but a collection can help heal the story. This is kind of an epiphany/self-care moment. Writing has dug up trauma for me, but it also is helping to heal the trauma. I think that healing is so important. A lot of times we writers create these beautiful pieces that highlight trauma, and then we share that work, and we live in those trauma-tinged words, and it feels immense. A collection is a bit like listening to a record all the way through. Sometimes you discover that the story was broader than expected.

Choosing a home for your second poetry collection may be more difficult than the first. Some would argue you have more choice in the matter, but on the other hand, there can be added pressure following a debut. How did you come to choose Rare Swan Press for Ceiling Fan?

Rare Swan Press chose me. I released an earlier version of Ceiling Fan as a self-publication. It garnered a surprising amount of attention, and Rare Swan Press asked to see it. I’m so grateful that they approached me. Otherwise, I would’ve self-published. I’d like people to read it, but I understand that there’s a lot of truly stellar work out there, new stuff every day, and with a saturated market like that, I didn’t expect to get noticed, especially writing the weird things that I do. So, again, I’m grateful.

Finally, if Ceiling Fan could take the physical form of a place, what would that place look like?

Maybe a grey room hurtling through space. Somehow a snake plant appears in the corner like a Boltzmann brain. It is not real, but the dirt is. The dirt particles jam the machinery. But it’s all fixable.